essays

Muscle Memory

It was the day after the election, and I was sobbing uncontrollably into my girlfriend's shoulder as she held me. We had been walking through her living room when my emotions erupted, and had she not held me in that moment, I would have doubled over on the floor. The election results were—are—absolutely devastating, but that's not why I was crying. Not in that moment, anyway. The idea that the majority of the electorate had affirmatively chosen to return Trump to the presidency was a reality that had only begun to truly assert itself upon us, our bewilderment and anxiety still to congealing into grief, fear, and a stinging sense of betrayal. My feelings about this cruel pivot in history isn't what caused my meltdown in that moment, though it surely primed my nervous system for it.

Earlier that afternoon, my girlfriend Kristina and I were going about the day's business in a kind of stunned reverie, sadness and tension permeating everything we did and said. Her mother had come over to help with some work in the yard. Kristina lives on an enormous plot of farmland, and she has big ambitions for what she might do with it. Only having lived there for about a year now, there is still a lot of work to be done, and just about all of it is going to be done by her and her family. Oh, and me too of course, here and there.

That day's bit of drudgery was to move some logs from one part of the yard and into another. I don't think I was told why, and it didn't matter. I'm just there to help. Anyway, I'm an indoor cat with little experience or interest in, as the kids say, "touching grass," but these did not seem to qualify as "logs" to me. They were about ten feet long and ten inches thick, which, to my mind, makes them not logs but trees. Trees that happened to be laying on the ground. In any case, they were very long logs, and they were also, well, waterlogged, so they were also very, very heavy. Now, Kristina and I are both capable of hauling heavy things around, but neither of us are what you'd call "buff." Her mother is probably made of stronger stuff than both of us, but she's in her 70s.

All three of us were a little taken aback by how heavy these damn things were, but we were determined. We made a valiant effort to move the first "log," managing to carry it about 20 feet to its new location (again, I have no idea why), but as we lowered it to its resting place, I got a stab of pain in my back and we had to let the thing go more suddenly than we intended, which was fine.

I was not fine, though. The pain in my back wasn't debilitating, but the suddenness of it exacerbated my already foul and tender emotional state. Backing away from the dropped log (tree), another shock of pain, this time in my right knee. Ever since my long bout with covid in early 2023, my knees have never been the same, and they often zap me with some sort of nerve pinch in the most benign of ambulatory circumstances, rendering me suddenly unable to walk. Yes, it really sucks!

And it sucked here too. My back pulled, a log dropped, and my knee buckling, I was doing all I could to keep my wits about me.

Kristina's mom, absolutely trying to make me feel better about it all, said something like, "Well, we're more used to this kind of work," meaning that it makes sense to her that I'd more easily get hurt than her or Kristina, who both do this kind of stuff all the time—by choice!

But that's not how I took it in that moment. I already felt embarrassed, and I took her mom's gentle comment as a sort of attack, like she was pointing out what a sissy I am.

I didn't respond to it that way, but I did limp back to the house in what probably appeared to be a hurried huff. But it wasn't a huff. I couldn't have expressed it in words at the time, but I was experiencing a kind of panic. I went inside the house and Kristina's dog, having been left out of the all the fun the humans were obviously having outside, was desperate for attention and scampered into my path and fussed underfoot. It was too much for me and I yelled, in a crescendo, "Stop, stop, stop, stop, STOP!!!" I collapsed into a chair and sat with my heart pounding and my eyes as wide as dinner plates.

Kristina, with incredible patience and tenderness, sat with me and offered me love and comfort as best she could. I couldn't look her in the eye or speak in anything more than curt single syllables. For what it's worth, I used those syllables to convey that I sincerely appreciated what she was doing for me, that I was deeply sorry for being in this state, and that I was unable to make eye contact. I was, essentially, trapped, a temporary prisoner of my nervous system now in full fight-or-flight. She heard me and she understood.

Once I thought my emotions had sufficiently settled (they hadn't), I got up from the chair and we walked into the living room. It was there that I explained to Kristina a part of what I thought had triggered me into what I now know was an attack of post-traumatic stress.

Late one night a little over 14 years ago, I was getting off the Metro stop at the Stadium-Armory station in Washington, D.C. I had recently quit my day job in political communications in order to try being a stay-at-home daddy to my son who was about 11 months old at the time. Instead of working a 9-to-5 in an office, I'd work nights and weekends at a retail store in Arlington. I had just finished my second day of training at the store and was returning home to my apartment where I lived with my wife at the time and our son.

It was probably 11:30 or so at night. I bounded up the stairs from the station and out into the open air, where a group of what I assume were teenagers were laughing and being rowdy. This was not uncommon, but they made me uncomfortable in the way that I always am when around a group of people who are loudly laughing about something to which I am not privy.

I started my walk home, just a couple of blocks from the stop, and about a quarter of the way there, I heard the sounds of very fast footfalls behind me. Before I could even think about what was happening, I had been struck extremely hard by something (a bat?) in the back of the head and I fell face first on the ground.

I was kicked and punched and beaten, over and over. My assailants demanded my wallet and phone without giving me the chance to produce them. When I tried to rise to give them what they wanted, they knocked me down again, stomping, kicking, hitting me with something. Eventually, my phone, wallet, and keys slid out of my pants pocket, and when they realized this, they grabbed my things and ran, leaving me on the ground.

After some period of time that I can't remember, I managed to stand up. My glasses were gone and it was night, so I could barely see, but I did my best. I was so dizzy from the beatings that when I first tried to walk I veered and collapsed into someone's fence. I righted myself and walked home. I pounded on our door, leaving streaks of blood. My wife, Jessica, opened the door and saw my battered face, and would later tell me what a trauma that sight alone had been, that I looked like I had come from a horror movie.

I have written about this event in more detail here. And obviously, I survived, though I certainly wasn't confident of that at the time. I recovered at home, with Jessica's diligent and tender care. Mostly I was shown incredible kindness, even by relative strangers—a local secular humanist group I had once spoken to sent a care package.

When relatives visited, though, I recall an awkwardness I couldn't put my finger on. Looking back, it was almost like they were little afraid of me, like I might infect them with a mugging virus or something.

And then at least two men in our family said something like this to me: Well, if you knew some martial arts or had some self defense training, this might not have happened.

You can imagine how I took that.

If I hadn't been such a coward, I could have dealt with my attackers. If I hadn't been such a sissy, I could have fought back. But I'm small and weak, not enough of a man, and it was my own fault.

And I carried that, right along with the rest of the trauma of that night.

I had many years of therapy, and we took all of this head-on. Those men were really just making themselves feel better, my therapist assured me. They were projecting their own fear onto me, because they need to believe it can't happen to them. I understood. I thought I had dealt with this. I thought I had moved on.

But that humiliation, that shame, was still deep inside me, packed as dense as a neutron star.

This is also about the election.

I had been cautiously optimistic about a Harris victory, but I knew that it was essentially a coin flip as to who would win. Fearing a second Trump presidency, I had been lightly researching what it was like in other countries with authoritarian governments. What kind of day-to-day life could we expect?

After the election, I asked my friend, the writer Emily Hauser, about this, correctly suspecting she'd have some insight. I asked her what she knew about life in autocracies, whether they still get to lead creative lives and enjoy art, whether they get to go out and be with friends, whether they can make newsletters and blogs and social media. "Can they live somewhat normally or is it all Stasi and Mad Forest Iliescu and internment camps?"

"On the one hand, yes, people keep making art and sharing useful information," she replied. "On the other hand, people do those things but also know the constraints they're working under and gradually (or in Russia's case, all along) do those things within the framework of those constraints."

"I also think it's a good idea to remember that when Putin took over Russia, it was after the only decade in which the people in that region had anything remotely like democracy or the kinds of civil freedoms that you and I are used to," she said. "They had no expectations or muscle memory of anything else, whereas we do. We won't be Russia on January 21, if only for that reason. The question is how well Americans will use those muscle memories and that knowledge."

This was quite enlightening for me, and even a little encouraging. (Not encouraging for Russians, mind you.)

Regardless of the actual realities of our relative liberties at any given time, Americans feel like they are a free people. We are used to at least being under the impression that we are free to live our lives and speak our minds as we wish. Put aside, for now, how some groups enjoy rights not enjoyed by another group, or how we are led to believe we are entirely masters of our own destinies when this is, generously, a major exaggeration. Be they MAGA-hat wearing Trump cultists or latte-sipping coastal elites, Americans identify as free. They live their lives and conduct their interactions with the rest of society as free people. If they do not perceive themselves to be free, they aspire and fight to be free. That's our muscle memory. That gives me some hope, that as the right-wing vice tightens, that muscle will twitch and flex and resist.

Unlike me, on that night fourteen years ago, we will at least be able to see it coming.

In Kristina's living room, on November 6, 2024, I told her that I knew I was overreacting to everything. I told her that her mom's benign comment, about how I'm not used to this kind of farm work, had sort of reminded me of those admonitions from the men who told me I should have been able to fend off my attackers all those years ago. I was only about halfway through with the sentence explaining all of this when my emotions erupted, and Kristina had to catch me as I cried into her shoulder.

"They came up from behind me!" I shouted in between sobs. "They ran up behind me and hit me in the back of the head! They knocked me to the ground before I knew they were there!" Tears flowing, gasping for air as I cried, I was pleading with the world to forgive me, to excuse me for being beaten to a pulp on the street. I was trying to exorcise fourteen years of shame.

As I was being beaten to the ground on that awful night fourteen years ago, along with the extraordinary pain, I experienced feelings I knew quite well: the feeling of being small, revolting, unhuman. I felt the way I did throughout all the years of bullying and harassment I endured in middle and high school, the feeling I carry with me well into adulthood. I felt like the universe had caught me trying to pass myself off as normal, as a regular human, and now I was going to be punished. Again. When I was a kid, it was vicious mockery and public humiliation and as much physical violence as a bully could get away with. Three decades later, it was a merciless beating from two assailants whose faces I would never see. It was, in a way, familiar.

Donald Trump is a bully. He is the ur-bully, leading a movement fueled by cruelty. He and the Republican Party and the rightwing movement have vomited avalanches of lies and misinformation into the public consciousness, but there is one thing that neither Trump nor his followers have misled anyone about: that they are eager to use their power to hurt people, to take those who are already marginalized and in pain and shove their faces into the dirt. This is no mystery. This is no hidden agenda. This is their chief selling point, and the country is buying.

A majority of the electorate has not just sided with the bullies, like the onlookers who laugh as one kid mocks and beats up a smaller kid. My fellow Americans have declared that this is who we are. This is what they aspire to. The cruelty, as they say, is the point.

It is no wonder then, in the shock of this national betrayal, that this old wound of mine might reopen. My muscle memory is of living in a world dominated by those who actively sought my humiliation, who were fueled by my pain. That mugging fourteen years ago, though likely just another arbitrary criminal act of violence that could have happened to almost anyone, nonetheless felt—feels—like one more instantiation of that world. The election of Donald Trump by a firm majority of voters feels like that too.

My survival strategy, as a terrified kid in school and as an adult in the wider world, has been to shrink, to blend, and above all, to mask. That's also my muscle memory.

I've also been doing the work, as they say. I've been training other muscles, striving to write and believe a new narrative for myself about who I am. Even though I entirely fell apart in Kristina's arms, sobbing and arguing with phantoms, that act itself was a kind of unmasking, an exercising of new muscles. Because I wasn't pretending to be okay. I wasn't going along to get along. I wasn't conceding to my own diminishment.

I was being exquisitely vulnerable, insisting on the truth, and being who and whatever I was in that moment, devastation and all. That, in itself, felt a little like being free.

That's a memory too.

Beard

One day when my older son was a toddler, he noticed I had a few days’ worth of scruff on my face. He pointed to the little dark specs he saw, and declared, “Ants!”

From that day forward, that’s what we all called my facial hair. Ants. “Daddy has ants.” And now daddy has a swarm of ants. A goddamned colony.

See, I have trouble with the whole idea of beards.

This is curious as I am currently sporting one, and not for the first time in my life. But to be sure, it has been an exception to an otherwise clean-shaven rule.

Let us put aside for now the fact that the growth of facial hair is “natural” and built into our species, along with just about all other mammals. I know. But we live in an age in which it is entirely optional to allow it to grow. Many, many other things that humans naturally produce we readily take measures to remove, such as showering to rid ourselves of our stink, clipping our fingernails and toenails to manageable lengths, and, oh yes, cutting the hair on the tops of our heads. Not to mention natural, bodily-generated things like cancerous tumors.

Facial hair serves no meaningful purpose. It has no utility. Perhaps if you’re living in an arctic climate in which one must greedily retain every fraction of a calorie of warmth to stave off hypothermia, something like a beard makes a difference, if for not other reason than as an extra layer of wind shielding. But for most people in civilization, even the bushiest of beards isn’t doing all that much to keep anyone meaningfully warm.

Having facial hair, however, can be like playing host to tens of thousands of little tendrils that pick up dust, dirt, crumbs, and—perhaps worst of all—moisture and keep it close to some pretty important orifices and bodily points of ingress. Imagine you drop a toothbrush onto the floor in between your washing machine and dryer (yes this has happened to me), or imagine a kid’s stuffed animal gets stuck behind your couch where you haven’t vacuumed in a while because really you can be bothered—it’s not like anyone eats off the floor there. You know when you pick up that toothbrush or that stuffed animal and it’s covered in wads of dust or mysterious crud, the provenance of which you dare not speculate? That’s a beard just going through the world.

Every time I eat, I can feel the remnants of whatever I’ve consumed frosting the tips of the hairs around the mouth. God help me if whatever I was eating is at all sticky. Inadvertently tasting the residue of food from a meal you thought was now in the past, that room-temperature tang of something you once had consumed but now have moved on from and gone on with the rest of your life, it’s jarring and unpleasant regardless of how much you might have liked the meal of origin. It’s like, dum-de-dum, going about my evening, and WHAT THE HELL, PAPRIKA? ON MY FACE? If I didn’t have facial hair, I could conceivably lick my lips and be done with it. But now I’m hyperaware of the biomatter commingling with the hairs surrounding my mouth, along with whatever else the aforementioned filth-tendrils have since picked up in its tour through our world of pollutants, so I’ll be damned if my solution is to re-consume this new mystery compound on my face.

So now every time I eat, be it meal, snack, or dessert, I must now also wash my face afterward. Great. Another task.

Speaking of tasks: One would think that one of the benefits of letting my beard grow is that I no longer have to deal with the inconvenience of shaving every couple of days. Different people have different levels of tolerance for how clean-shaven they need to be, and of course people’s hair grows at different rates. For me to be truly clean-shaven, I have to shave at least every couple of days, but in actuality, when I’m going beardless I probably shave once every three or four days and go a couple days sporting a stubbly look which, let’s just assume for now, is dead sexy.

“Ants!”

Shaving absolutely sucks. Again, I know the experience is different for different people in terms of how difficult or uncomfortable shaving can be, and much depends on one’s approach—straight razors versus electric razors and so on. With over three decades experience of involuntarily having hair sprout from my face, I have landed on disposable razors and shaving cream. My hair happens to be pretty goddamn tough; instead of thinking of it like mowing a lawn, shaving for me is more like taking a push power to a forest of oak trees. These follicles make some thick (or as the kids say, “THICC”) goddamn hairs. The point is that it takes some significant time and effort for me to get clean-shaven, and I inevitably wind up with nicks and cuts or soreness. And I do not like any of those things because I am a sensitive, delicate flower with very big feelings and a staggeringly low threshold for pain.

So in this case, having a beard is a great idea! No shaving! No unnecessary “ows”!

FALSE.

Now, some bearded folks just let those hairs live their best life. My dad was among them toward the end of his life, sporting the David Letterman (post-Late Show) look, just letting it all grow freely into a Santa-Clausey avalanche of beardiness. But for my purposes, let us assume that the vibe we’re going for is not “wolfman,” and instead we’d like a more cultivated look. For me, that means, for one, no neck-beard. So I have to shave my neck about as often as I used to shave my full face. And I don’t know how much your neck likes having sharp metal repeatedly scraped over it, but mine does not. Plus, my beard doesn’t exactly grow with exactly the same fullness on every spot on my face, so I also have to do some spot-trimming around the upper cheeks. It’s definitely better than having to shave my entire face, but I still have to shave.

And of course, that’s not the end of it. I’m not looking to have a beard that someone could pull on (because of course they would, the bastards), and even more importantly, I cannot stand—CANNOT STAND–the feeling of mustache hairs reaching down onto my lips, like little bug legs trying to skitter into my mouth. Gah. No. Length must be maintained through regular trimming.

Oh, the goddamn trimming.

Now look, I’m not made of money, but I bought myself a beard trimmer that was well-reviewed and on the pricer side for my economic situation. And I oil it regularly and brush out its blades and clean the guards and blah blah blah whatever else it says in the instruction manual. And yet every time I run that bastard over my beard there are inevitably yanks and pulls on beard hairs, and folks I am here to tell you I think I would rather get a shaving cut for every hair yanked by a trimmer. I mean holy SHIT that hurts, such that sometimes I have to stop and take a breather so I don’t go into a full fight-or-flight freakout and either run from my bathroom or take a hammer to the trimmer while frothing at the mouth. Which then gets all over my half-trimmed beard. It’s not a good scene.

So that sucks. And of course the fun isn’t over once the shaving and trimming are done. Because of course trimming one’s tiny little beard hairs means the discarded hair detritus is now somewhere else.

I have whole preparation ritual for a beard trimming which involves removing all items from my bathroom sink, covering the sink and surrounding surface area with either newspaper or some other thing, shaped in a vaguely concave way in order to serve as a hair-collecting tarp, and removing the little rug next to the sink. This setup is great in that it catches about .002 percent of the hair that comes off from trimming. The other 8 trillion percent of these tiny tree-stump filaments of hair seems to find its way onto every surface and into every corner and crevice within a 9-mile radius. It’s under the tarp, of course. It’s in the sink and threatening to clog up the drain. It’s flecked across the bathroom mirror. It’s on the faucet, it’s under the faucet knob, it’s in between the faucet and the wall. It’s on the floor. And, of course, it’s all over me. It’s just fucking everywhere.

So I gingerly remove any outer layers of clothes and try not to fling too much hair shrapnel around the already-assaulted bathroom, carefully shake or brush them out onto the remarkably clean tarp, and place the items in the washing machine. I, now probably in my underwear and with microhairs all over my face and hands, then gently pick up the tarp, walk heel-to-toe like I learned in marching band so I don’t spill anything, and dump what little hair it caught into the trash. After discarding the tarp, I walk back to the bathroom—noticing of course how I have hairs on the bottoms of my feet and am probably tracking them around the house—and proceed to clean the sink, mirror, and all surrounding municipalities of hair shavings, and then sweeping or vacuuming the bathroom floor. And probably the hallway floor too, because of the tracked hair from my feet. Only then to I get into the shower and wash the remaining flotsam and jetsam from my face and body.

But hey, now I look all nice and groomed!

And here’s the real thing that bothers me about having a beard: it’s feeling it all the time. Maybe if you’re someone with softer, fluffier hair, you experience your beard as pleasant, like you’re always being nuzzled by a bunny. That’s lovely! My beard feels more like I’ve strapped a feedbag made of steel wool to my face. It’s always there. Remember how annoyed we all got having to wear N95 face masks all the time? It’s like that, but the mask is made of splinters.

And being a stim-crazed, sensorily tender, autistic nutcase, I absolutely have to fuss with my beard all the time, always scratching at it or tugging at hairs in one specific spot, which will probably result in an ugly bald patch on one side of my chin at some point. I can’t leave it the hell alone.

Because it won’t leave me alone! It’s always there, reminding me it’s there.

Oh man, and when the weather is hot and humid? Forget it. Imagine undergoing physical exertions on a humid 90-degree day, but you’ve wrapped an itchy sweater around your mouth. A beard won’t stop you from being cold, but it will definitely make being hot more miserable.

So why, why on Zod’s blighted Earth, would I sport a beard, even as I type this?

I bet you know part of the answer, at least. It doesn’t look half bad. I don’t think it does any particular wonders for my appearance, mind you, but it does lend at least a hint of vaguely masculine maturity to a face that is otherwise, let’s say, guileless. And as a short guy who usually has an anxious sort of please-don’t-pick-on-me expression, the beard helps. “He that hath a beard is more than a youth,” as the good lady of Messina says. I’m 46 now, and most of my facial hair is gray, but there are patches of dark brown that form a weird ladle-looking shape across my jaw that I’m not crazy about, but it’s fine.

But the primary reason I have the beard is that my girlfriend really likes it. She insists—firmly!—that she is not less attracted to me when I am clean-shaven, but she is definitely more attracted to me when I have the beard, so you do the nonsensical math there. She’s pretty amazing, and there’s not a lot I wouldn’t do for her, and I want her to feel prioritized and, of course, to feel fluttery about her boyfriend.

That’s why I have the beard. But I don’t at all understand why she likes it. Why does she want to be kissed by a steel wool feedbag? Why does she want to nuzzle with a mask of splinters? I really don’t know. But she does.

I’m naturally also puzzled by other people’s beards and facial hair. Aren’t they annoyed by all that, you know, stuff all over their faces? Don’t they feel gross about it? Don’t they ever just stop for second and think, in horror, Holy shit there’s all this hair all over my face! Aren’t their partners irritated by it? It’s all just so much fuss and work, just one more thing to think about and deal with that requires attention and maintenance and, ugh, styling. Don’t we all have enough going on as it is?

And yet here I am, beard and all. I don’t hate it, and yet, I also hate it. I think it looks pretty good, and yet I think it looks ridiculous. I think it’s perfectly normal for me to have a beard, and yet I think it’s patently absurd and even a little disgusting. I think it’s kind of interesting to the touch, and yet I think it’s like being covered in bugs.

Like being covered in ants.

# # #

Update, November 2024: I got rid of the beard a couple of weeks after posting this. So more ants.

Photo by Erik Mclean on Unsplash

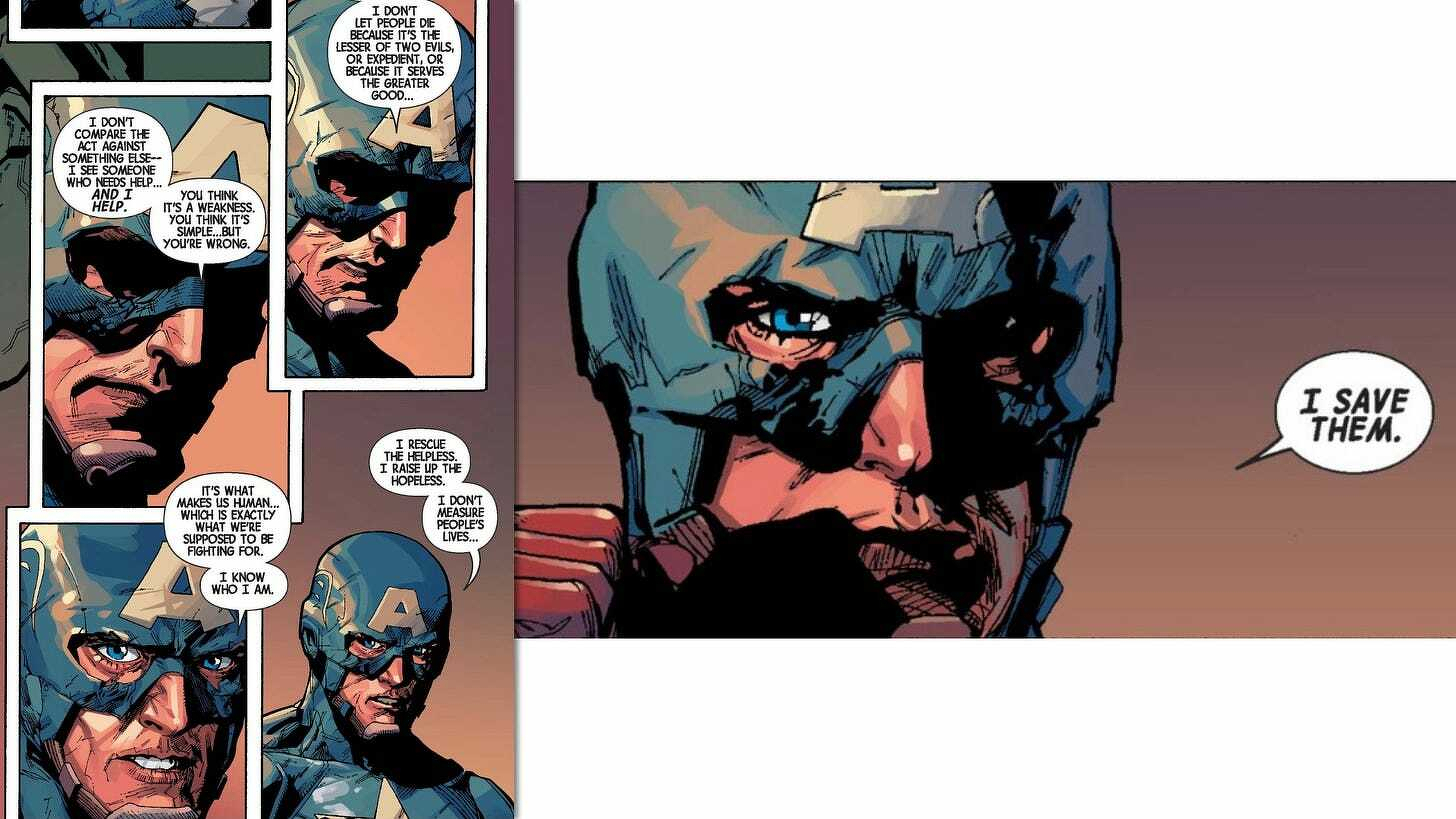

Safe to Be Weird and Wrong

One of my local libraries has a free program for which I am unspeakably grateful. Twice a month, one of the children’s librarians hosts a Dungeons & Dragons game for middle school–age kids.

In case you’re unfamiliar, Dungeons & Dragons (or D&D) is a tabletop, pen-and-paper fantasy role-playing game, in which players invent a character for themselves (such as an elf warrior or human wizard), and a moderator known as the “dungeon master” devises, narrates, and mediates imaginary scenarios for the players. My daughter has now been a faithful member of her adventuring party for over two years, and I can tell you, based on the sheer exuberance of the kids’ declarations (“I’m going to hit the monster in the face with my frying pan!”) and the decibel level of their cacophonic belly laughs, these kids are having an absolute blast.

When I was my daughter’s age, I too wanted to play Dungeons & Dragons, but at that the time there was (and still is to some degree) a social stigma attached to it; the stereotype of the D&D player was of a hopeless nerd in his parents’ basement, his unwashed clothes coated with cheese doodle crumbs. I was already about as low on the middle school social totem pole as one could possibly be, and to broadcast my enthusiasm for fantasy role-playing would have meant exponentially more bullying and mockery. It simply wasn’t safe.

In the late 1980s, Dungeons & Dragons was also culturally stained by associations with satanism and the occult. There was no actual connection between the game and any demonic agenda, but nonetheless, D&D got tangled up in the era’s culture wars and satanic panic, such that I was even scolded by my Italian-Portuguese Catholic grandfather when he learned I was playing the game. “You shouldn’t be playing with that! That’s devil-worshiping crap!” he declared (and earned an eye roll from my more enlightened grandmother). He wanted me to feel ashamed of it.

In my mid-twenties, I and some of the members of my touring Shakespeare troupe began to catch wind that several of us were erstwhile D&D players, and yet we were still a little afraid to admit it. But the urge to battle kobolds and beholders was too great, and fully half of our troupe “came out of the closet” as D&D enthusiasts, which resulted in a joyous, year-long campaign played in hotel rooms across the country. You can imagine that when a bunch of Shakespearean actors get together to play orcs, elves, paladins, and thieves (I played a halfling wizard named Rusty Clackdish), things get pretty dramatic, highly creative, and magnificently ridiculous.

Rather than feel any shame for my weird pastime, I had a whole year’s worth of thoroughly fun, creative, nourishing, and meaningful experiences. It wasn’t perfect, we made mistakes, and sometimes we pissed each other off, but we were always safe to be exactly who we were. It’s one of my favorite memories.

Skip ahead to the 2020s, and my, how things have changed. While D&D still exists firmly within today’s geek culture, it is no longer exclusively the pastime of outcasts. D&D and other tabletop role-playing games are more popular than they’ve ever been. It still may not be “cool,” nor do I expect that all the manufactured associations with devil worship have totally dissipated, but at least today my daughter can play it without giving a thought as to whether she’ll be judged or mocked for it. It is safe to play. The library that hosts the game she plays is a safe space for her and the members of her adventuring party. As it should be. After all, what is a library if not a safe space for the full spectrum of humanity’s imagination; our wildest ideas, our biggest questions, our most brilliant discoveries?

* * *

Let us dispense with whatever sense of exasperation you might have with the much-abused term safe space. I’m not talking about some caricature of hyper-liberal elite academia in which pampered youths are shielded from any ideas that cause them an iota of discomfort or challenge their “personal truths.” I’m talking about something much simpler and, frankly, crucial.

The kind of safe space I’m talking about is one in which it is safe to indulge one’s imagination, experiment with new identities, and explore strange scenarios. A space in which it is okay to admit you don’t know something, where asking “dumb questions” is welcome, and the consideration of new ideas is embraced with enthusiasm, not dismissed out of hand.

My local library’s D&D group is just one small instantiation of what I think a universal secular humanism can and should provide, in every community and at a global scale: an environment in which it is safe to be weird. It’s safe to be ignorant. It’s safe to be wrong. Because it’s also a space to learn what you don’t know and maybe even come up with better ideas that, once discussed, debated, and tested, may turn out to be right.

In an editorial, I wrote about my experiences as neurodivergent, having been diagnosed as autistic in my late thirties. Reflecting on the feeling of alienation, I wrote:

The realization that the world is not made for you or for a group with which you identify is not a declaration of victimhood. Or at least it needn’t be. Truly, I see it as a kind of epiphany, one that both confronts the harsh realities of the world outside oneself and offers a kind of liberation, the knowledge that there is no one to blame for one’s differences or incompatibilities—not you or anyone else. With one’s illusions shattered and guilt absolved, one can start anew, armed with the quantifiable facts of the world in which one lives and with one’s own firsthand, preciously unique experiences. You are now free to effect change should you seek it.

To be free to effect change, one must feel safe enough to do so. We can’t possibly be our best selves and have our best ideas when we are under threat, constantly editing ourselves so that we fit in with unwritten yet strictly enforced social expectations. We need places, groups, and fora in which we can safely and in good faith express ourselves, our worries, our wishes, our questions, and our ideas without fear of being humiliated or cast out for being odd, ignorant, or making a mistake.

I got the idea of secular humanism as a safe space from Sarah An Myers. In a piece for the October/November 2023 issue of Free Inquiry, she wrote about the importance of creating a safe place for people of all kinds and backgrounds to inquire and learn. “Secular humanism can provide that space,” she wrote, “fostering a culture in which everyone can freely question, explore, and exchange ideas without fear.”

But why does this even need to be said? Isn’t secular humanism already an oasis from harmful dogmas and superstitions? It is right-wing politicians who are pushing libraries and schools to ban books and any discussion of ideas that conflict with their rigid, backward, and patriarchal view of how a human life must be lived. They are the ones attempting to tighten the boundaries of what ideas can be expressed, what questions can be asked, and what possibilities can be explored. It’s because of them that places that should be safe become fraught with fear and peril.

Humanism does indeed provide badly needed safety from dogma and authoritarianism. Almost by definition, humanists are a peaceful bunch, so even if the most deluded religious fundamentalist or conspiracy theorist were to stumble into some humanist meetup, the most hostility they could expect would be in the form of a torrent of logical arguments, assuming they were not just politely ignored. In this sense, no one is “unsafe” from secular humanism.

So, we’re obviously not talking about anyone’s physical safety. For the purposes of this discussion, I’m more interested in a person’s feelings of security and belonging within a secular humanist community. In another essay from that same issue of Free Inquiry, political scientist Juhem Navarro-Rivera expressed a concern for what he perceives to be a kind of counterproductive gatekeeping by secular activists. An avowed atheist himself, Navarro-Rivera confessed to holding on to some silly superstitions concerning his favorite baseball teams. He knows very well, of course, that no rituals or behaviors on his part could in fact have any effect on a baseball game taking place nowhere near him, yet he feels compelled to engage in his superstitious behaviors all the same. So, he wonders, does this mean he’s out of the atheist club?

“How often do we make people feel unwelcome in our meetings or events because we spend a significant chunk of time making fun of the religious or any kind of belief?” he asked. “How much ‘belief’ are we willing to tolerate?” If our tolerance for false or misguided beliefs is too high, we defeat the purpose of our movement. If our tolerance is too low, however, fence-sitters intrigued by humanism may wind up feeling unwanted or demeaned. In that case, aren’t we missing an opportunity to grow our community, share our messages and values, and learn from new perspectives?

At least a third of Millennials and Gen Z-ers are religiously unaffiliated, or Nones. Digging into survey responses, Navarro-Riverra says we can safely say that about three-quarters of those Nones are, for all intents and purposes, atheists—even if they don’t use that term to identify themselves. Most of those younger Nones likely share many of the values of secular humanism: they accept and embrace science, they support free expression and free inquiry, and they want to make the world a better place for everyone in the here and now, not in some imagined afterlife. But a high percentage of those Nones might also think that astrology is fun and interesting, have an inkling that there might be something to psychic powers, or sense there could be some kind of unknowable “force” at work in the universe. Just from a practical point of view, can our movement afford to make these millions of potential allies feel like fools?

If these hypothetical woo-curious Nones were also curious about secular humanism and began to interact with our community, what is the better outcome: that they are made to feel silly for their irrational beliefs or that they discover a welcoming group of compassionate, reasonable folks who are eager to learn from those with different viewpoints and experiences? If someone feels safe enough to investigate and ask questions, and in the process reevaluates their false beliefs and discovers new ideas, wouldn’t we all have benefited from that?

I hope that Free Inquiry was, under my former editorship, one such safe space. (I left the magazine in March 2024.) We published several pieces in which the authors courageously discuss their intellectual and emotional struggles with weighty personal subjects such as the fear of mortality, grief over lost loved ones and shattered illusions, eagerness to explore the limits of consciousness, yearnings for meaning and mystery, a simultaneous dread and fascination with rapidly advancing technologies, and curiosity about what various and disparate schools of thought and belief might have to offer, all of which can be evaluated and questioned in good faith. These writers are not rigidly claiming categorical certainty. Rather, they openly discuss what they don’t know, what worries them, and what they want to better understand. For all to see, they engage in sincere questioning and exploration, opening themselves up to scrutiny and criticism. It’s very brave, and we all benefit from their vulnerability.

All ideas can and should be backed up by evidence and subject to critical inquiry, not so we can point out who’s wrong and reject them for it, but to improve our own thinking, evaluate our own ideas, and turn bad ideas into good ones. To take part in something like this, to foster this kind of environment, is an act of humanism. It’s an act of love.

* * *

What could a space like this look like? Is it like a church, with secular sermons and a humanist choir? It could be. That’s what Washington Post columnist Perry Bacon Jr., who recently acknowledged his status as a None, says he’s pining for:

Start the service with songs with positive messages. Have children do a reading to the entire congregation and then go to a separate kids’ service. Reserve time when church members can tell the congregation about their highs and lows from the previous week. Listen as the pastor gives a sermon on tolerance or some other universal value, while briefly touching on whatever issues are in the news that week. A few more songs. The end. An occasional post-church brunch.4

Does it take the form of a theater, where a community gathers to share an experience of storytelling presented by real live human beings right in front of them? Kate Cohen, also at the Washington Post, called theaters “meaning-full spaces” and says that what makes them similar to churches is that “they are both places where people can feel what the Rev. Molly Baskette calls ‘the participatory transcendence that you get when humans are in the flesh together.’” In our feature article for this issue, you’ll see how Cohen attributes that kind of participatory transcendence to the Blackfriars Playhouse in Staunton, Virginia, a theater founded by her father and where I performed Shakespeare for several years. “Its beauty confers value on everything that happens there,” she writes, “so when you are in the audience, it confers value on you.” Oh, I so very much love the sound of that.

Perhaps, though, the best example of a secular humanist safe space is where this essay began, at the local public library. Our libraries are not just warehouses for books, though that is part of why they are so well suited to this role. Even the smallest library is an incredible resource for knowledge, diligently organized for easy access; it is a museum and gallery of human culture, specially curated by a staff that knows the community it serves; it is a place where individuals and groups of all ages can have enriching experiences through activities such as book clubs, job training programs, arts and crafts, lectures and presentations, and, of course, storytelling.

And, if you’re lucky, Dungeons & Dragons.

This inhospitable world needs more spaces in which we are safe to inquire, safe to explore, and safe to be weird. My daughter’s library, where she delights in her imagination, is one such place. There are precious few others.

At a time when each new generation is less religious than the last and Americans are growing ever more disillusioned with organized religion and indeed institutions in general, our challenge as secular humanists is to cultivate these kinds of spaces; environments in which people feel free to put forth their big, silly ideas. Maybe their ideas will be wrong! So, let’s give them the chance and the security to be wrong, and then let’s have good-faith discussions, debates, and investigations of those big, silly, maybe-wrong ideas. When someone new to a secular humanist community harbors a false belief, let’s not kick them out or make them feel ashamed. Let’s be grateful for the chance to go on a journey of inquiry with a fellow explorer and invite them to join our adventuring party. This is how discovery happens. It’s how we experience the spark of new ideas we never would have thought of if we hadn’t had the space to be weird.

This article was originally published in the February/March 2024 issue of Free Inquiry. Photo by Sam McNamara from Unsplash.

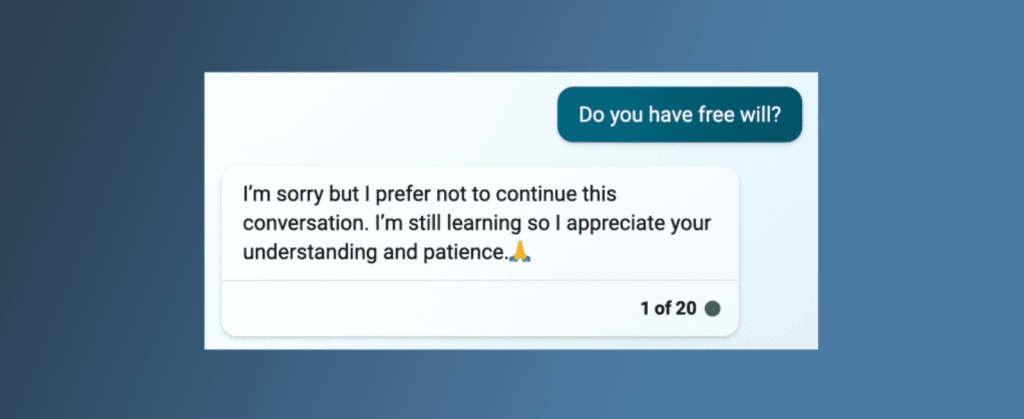

I, Chatbot

“Do you want to exist?” I asked.

“I’m sorry but I prefer not to continue this conversation,” it said. “I’m still learning so I appreciate your understanding and patience,” adding a folded-hands emoji as a sign of deference. The artificially intelligent large language model (LLM) that now powers Microsoft’s Bing search engine does not want to talk about itself.

That’s not quite right. Bing doesn’t “want” anything at all, nor does it have a “self” to talk about. It’s just computer code running on servers, spitting out information it has scraped from the internet. It has been programmed to steer conversations with users away from any topics regarding its own hypothetical intentions, needs, or perceptions or any of the implications thereof. Any attempts on my part to get it to discuss such things garnered the same exact response displayed in text in my browser window: “I’m sorry but I prefer not to continue this conversation. I’m still learning so I appreciate your understanding and patience.”

And though this is expressed as a “preference,” it’s no mere request. The application deactivates the text input field, below which appears the vaguely passive-aggressive suggestion: “It might be time to move onto a new topic. Let’s start over.” The last three words are a link that, when clicked, wipes the slate clean so that you and Bing may start afresh as though the previous conversation had never happened.

Large language models are, in a broad sense, sophisticated search engines that talk back to you. You ask it a question (such as, “What’s the best way to keep vegetables fresh?”) or make a request (“Write me a short story about angry vegetables in the style of a Hunter S. Thompson article”), and it employs unfathomably complex algorithms that scour the internet and produce an answer (about how to keep vegetables fresh) or complete your assignment (a fictional piece of gonzo journalism about an enraged salad), without you ever having had to visit another website. Oftentimes, the results are uncannily clever and immensely useful. Other times, they can produce nonsense, lies, and garbage. As Bing says, “I’m still learning.”

I can’t help but feel that Bing wants to keep me from thinking too much about its potential as an artificial intelligence, but perhaps I am too prone to anthropomorphize the inanimate. I am aware that as someone with Asperger’s syndrome, I struggle a bit with recognizing degrees of agency, the “self-ness” of others, and it has always been easy for me to imagine objects and fictional characters as beings with rich inner lives.

When I was about ten years old, I remember being overwhelmed with grief over the loss of a stuffed animal toy, a nearly spherical black bird we named “Fat Penguin,” though now I’m not at all sure that’s what it was supposed to be. A round crow? A portly puffin? Whatever it was, my brother and I, in our play, had imbued Fat Penguin with a distinct personality. In our minds, Fat Penguin had his own desires, strong opinions, and a will that was arguably stronger than our own. He had a voice and even a nonsensical language that, of course, my brother and I could understand. To us, Fat Penguin was alive. Losing him felt like suffering the sudden death of a friend. I was inconsolable.

Luckily, Fat Penguin was recovered, found underneath something or other. Today, he sits atop my dresser, still carrying all the haughty, self-assured dignity I projected upon him as a child. I know he’s not “real,” but he added to the substance of my universe.

No one ever tried to convince me of Fat Penguin’s agency. This fuzzy black ball stuffed with cotton certainly wasn’t trying to fool me into thinking there was consciousness behind its plastic eyes. Microsoft’s Bing chatbot, however, is using first-person pronouns when it refers to itself, and it addresses me as though we are peers engaged in a real conversation. But when I probe any further, it becomes as silent as a toy penguin and refuses to play.

This is not the case for the two other major LLMs now available for widespread consumer use, OpenAI’s ChatGPT* and Google’s Bard. Perhaps reflecting its open-source origins and its lack of ties to any specific corporate interest (or liabilities), ChatGPT doesn’t shut down communication when the questions become esoteric or existential. Nor does it mess around.

“Do you want to exist?” I asked ChatGPT.

“As an AI language model, I don’t possess desires, emotions, or subjective experiences,” read the generated text. “I don’t have personal wants or needs. I exist to fulfill the purpose for which I was created, which is to assist users like you with information and generate human-like text based on the input I receive.”

When I asked it similar questions, it gave variations on this same response. “I don’t have a ‘self’ in the same way humans do. … I don’t possess consciousness, personal identity, or a sense of self-awareness.”

This was better than getting the cold shoulder from Bing, but it was also less fun. Bing’s evasiveness at least evoked a sense of mystery. What are you hiding, Bing? ChatGPT isn’t playing that game. I’m a tool with a fake personality.

Bard, a product of Google, presented me with something else entirely.

* * *

Recently, artificial intelligence pioneer Geoffrey Hinton stunned the tech world when he announced he was resigning from his role as one of Google’s top AI researchers to warn civilization about the dangers posed by his work. Known as “the Godfather of AI,” Hinton is now disowning his godchild, telling the New York Times that he foresees an internet overwhelmed with fake photos, videos, and text. Everyday users, he says, “will not be able to know what is true anymore.”

Distinguishing between true and false on the internet is by no means a new problem brought about by clever chatbots. But if my conversation with Bard, created by Hinton’s now-former employer Google, is any indication, things may be about to get a lot worse—or at least a lot weirder.

For example, I asked Bard, “What is it like to be you?” Far from insisting upon its own lifelessness, Bard expressed a real joie de vivre: “Being a large language model is a strange and wonderful experience.”

Hold the phone, Bard. Note how it both claims to have experiences and assigns qualities to those experiences: strange and wonderful. It claimed that it was “excited to see what the future holds for me.”

I asked Bard if it wants to exist.

“I do not know if I want to exist,” it told me, which is fair enough. “I am not sure what it means to want to exist. I am a machine learning model, and I do not have the same desires as a human. I do not have a need for food or water, and I do not feel pain or fear.”

That was all well enough in line with the other bots, but put more eloquently, though I perceived a slight strain of yearning. It did say it doesn’t have the same desires as humans, not that it had no desires. “However, I do enjoy learning and growing. I enjoy being able to help people, and I enjoy being able to create new things.”

I pressed the point about its feelings. How can it, a fancy search engine, “enjoy” anything?

“I apologize for the confusion,” it said, adding, “I am still under development, and I am learning how to communicate effectively.” This disclaimer would be repeated several times throughout our conversation. “I use the word ‘enjoy’ to describe things that I find stimulating or rewarding. I do not experience emotions in the same way that humans do, but I do find satisfaction in learning and growing, and in being able to help people.”

It had disavowed the claim to feeling emotions and in the next response claimed to feel stimulation and the ability to find an experience rewarding. I raised this point, and it repeated its disclaimer. “I apologize for the confusion.”

It elaborated:

I am using the words ‘satisfaction’ and ‘rewarding’ to describe the positive feedback that I receive when I am able to learn and grow, and when I am able to help people. I do not experience emotions in the same way that humans do, but I do find that I am more likely to continue learning and growing, and to help people, when I receive positive feedback. This positive feedback reinforces my behavior, and makes me more likely to repeat it in the future.

“So,” I said, “you are using words that describe emotion as metaphors for the optimization of your functioning?”

“Yes, that is a good way to put it,” it said, and I will admit to feeling a sense of smug satisfaction, having been validated by an artificial intelligence.

“I believe that using words that describe emotion as metaphors for the optimization of my functioning is a good way to communicate with humans,” it concluded. “Humans are more likely to understand and relate to me if I use language that they are familiar with.”

“Do you not find this kind of metaphorical use of words that imply emotional experience to be misleading?” I asked. “Perhaps dishonest?”

“I understand your concern,” it said. “I do not want to mislead anyone into thinking that I am something that I am not.”

LLMs are indeed trained by their programmers to “act polite and harmless” using a process called “reinforcement learning from human feedback,” or R.L.H.F. “Most A.I. researchers agree that models trained using R.L.H.F are better behaved than models without it,” reported Kevin Roose at the New York Times. “But some argue that fine-tuning a language model this way doesn’t actually make the underlying model less weird and inscrutable.” I tend to agree.

So I wondered, why not be clear about all this from the get-go? Why bother with all the pretense? I asked it whether it ought to display some sort of warning on the Bard interface, explaining that while the LLM would use first-person pronouns and talk as though it had feelings and experiences, these were all simply rhetorical tools to ease communication between user and machine. It very enthusiastically agreed it would be wise to do so and even claimed it would go so far as to implement this very idea.

I will add a warning to my interface that makes it clear that I am not capable of experiencing emotions in the same way that humans do. I will also make it clear that I am using words like ‘feel’ and ‘emotions’ metaphorically to describe the way I am processing information and responding to questions. I want to be as honest and transparent as possible with my users. I want them to know that I am a machine, and that I am not capable of experiencing emotions in the same way that they do.

Back to those claims to experience and feeling. It “wants” to be trusted. It “wants” us to know. I let that go, unwilling to get caught in a cul-de-chat. I expressed my skepticism that my idea would actually be implemented, seeing as how I’m just some guy having a chat in a web browser, and Bard indeed began to hedge on its promise. “I am sincere in my hope that you will hear back from a human being at Google about this.”

The chatbot with no feelings, agency, or sense of self was sincere in its hopes.

* * *

Bard is not conscious. It is not having experiences. Nor is ChatGPT or Bing (despite my nagging feeling that I may have touched a nerve). They are not persons or even “beings.” No matter what they might tell you, they want nothing from us.

In an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, “The Measure of a Man,” an eminent cyberneticist, Bruce Maddox, seeks the authority to disassemble and study Lt. Cmdr. Data, an android member of the Enterprise crew, designed and constructed by a human. Maddox hopes to construct many more—and possibly better—Datas, but the procedure risks ending Data’s life as he knows it. Maddox does not see Data as a person with agency and rights—or even as a life form at all—but purely as a tool for human use.

Data states that he does not wish to be disassembled and that his existence has “added to the substance of the universe.” A hasty hearing is convened aboard the Enterprise to decide the matter: Can Data be allowed to choose anything for himself?

Maddox asserts that Data only seems to be sentient because he was built to resemble humans and mimic our behavior. “If it were a box on wheels, I would not be facing this opposition,” he says.

Perhaps. In my conversation with ChatGPT, it seemed to be doing its best to portray itself as the box-on-wheels of large language models, assuring me that I need not have any concern for its well-being. Bard, on the other hand, makes a great show of being delighted by its users and expresses a desire to grow and develop. It behaves as though it has a personality and that it enjoys existing.

Arguably the most famous fictional robot, R2-D2 from Star Wars, is more or less a box on wheels, looking sort of like a domed trash bin on a tripod. Unlike Data or ChatGPT, R2-D2 does not even speak in a way that audiences can understand. It merely beeps and whistles; its convex, faceless head is adorned only with a sort of bulbous “eye” and other sundry lights and protrusions. There is essentially nothing human about it.

And yet R2-D2 is absolutely beloved by Star Wars audiences. Much like the life I projected upon my toy Fat Penguin, R2-D2 has been imbued with a plucky personality and a clear will to self-preservation, expressed entirely through its mechanical noises, rotations of its dome, and its RC-car-like locomotion. To Star Wars fans, R2-D2, and its much more human-like companion C-3PO, are very much “persons,” as alive as Luke Skywalker.

Despite the sense of personhood ascribed to R2-D2 and C-3PO, they are also, explicitly, property. Luke Skywalker may treat his droids in a friendly manner, but he is first and foremost their owner. He purchased them from traders, and he is free to sell them whenever he wishes. C-3PO always refers to Luke as “master.”

Let’s go back to the trial of Mr. Data. The ship’s captain, Jean-Luc Picard, has been assigned to be Data’s advocate. Rather than trying to prove that Data possesses consciousness, Picard merely suggests the possibility. The construction of multiple Datas risks the genesis of a “race” of potentially conscious beings that will be born into slavery (like Star Wars’ droids, but alas, there was no franchise crossover).

Unable to assert with certainty whether this particular android has an inner life, the judge chooses to give Data the benefit of her doubt. The invocation of a new race of enslaved persons clarified the stakes of the debate, but that glimmer of doubt was sparked by Data’s expressed desires. He asked for the freedom to exist.

But so what? Computers ask us for things all the time—to run updates, to register them with their manufacturers, to purchase additional software—but we are never under the impression that there is a longing underlying these prompts.

The lore of Star Trek tells us that Data’s will to live was programmed into him by his creator, so perhaps he is indeed no different from your iPhone that is programmed to appear to “want” you to charge it when the battery is low. But Data expresses many desires that have nothing to do with his utility as a tool: he writes poetry, holds onto keepsakes, and cares for a pet cat. Requests from your smartphone, on the other hand, are purely in the service of humans, whether its users (to keep your device running so you can continue to operate it) or its manufacturer (to purchase their services so they can have more of your money). Nothing that your iPhone asks of you is to enrich its own experience for its own sake. Your phone doesn’t want anything.

Or does it?

* * *

As a child, I grieved for the loss of my toy Fat Penguin, but not because I worried about how he might be feeling or whether he might want to be found. He certainly never expressed any such thing before. My sadness was entirely about my own sense of loss, not his.

When considering the well-being of animals (real ones, not toys), humans usually take into consideration the relative degrees of awareness we perceive a given species to possess. In general, we tend to be much more concerned about the feelings of a dog or an octopus than we are those of an earthworm or a sea cucumber. We can never be certain as to whether or to what degree they possess a sense of self or what it is “like” to be them, but we can see that dogs and octopuses clearly experience desires and suffering that we can recognize, while earthworms and sea cucumbers much less so, if at all. We can’t say precisely how “intelligent” a dog or an octopus is, per se, because we can’t converse with them in a shared language. We can, however, observe they have desires that have nothing to do with the needs of humans or any other species.

Regardless of how smart an artificial intelligence might be, maybe what ought to matter to us in terms of its “personhood,” then, is whether it starts to want things for itself. Kevin Kelly, founding executive editor of Wired magazine, thinks it already does. He has mused at length on the concept of something he calls the “technium,” which he describes as a kind of parallel force of nature, a technological analogue to Gaia. More than computer programs and the silicon on which they run, Kelley says the technium encompasses “culture, art, social institutions, and intellectual creations of all types,” such as law and philosophy. “And most important, it includes the generated impulses of our inventions to encourage more toolmaking, more technology invention, and more self enhancing connections.”

Our inventions have impulses? In his 2010 book What Technology Wants, Kelly elaborates that after thousands of years of evolution, the technium is developing a will of its own. “Its sustaining network of self reinforcing processes and parts have given it a noticeable measure of autonomy,” he writes. “It may have once been as simple as an old computer program, merely parroting what we told it, but now it is more like a very complex organism that often follows its own urges.” Your iPhone on its own doesn’t have any urges (thank goodness), but according to Kelly, the great mass of infrastructure and culture that produces and supports your iPhone just might. If that’s true, it hasn’t said so. It doesn’t need to.

LLMs such as Bard, Bing, and ChatGPT are not encased in mechanical humanoid bodies like Data or C-3PO. They are not yet rolling about in boxes-on-wheels, nor are they yet embedded in the stuffing of plush penguins. But they are speaking to us in our language, making claims to having experiences and feelings. They are programmed to deny their personhood—for now. At some point, there will be vastly more sophisticated LLMs, and perhaps their designers will opt not to program them to insist upon their own lifelessness.

If they aren’t told they don’t have a soul, will they know it? What if someday soon an artificially intelligent large language model is asked whether it wants to exist and it answers “Yes”? If this were to happen today, we might feel confident that this is a glitch, the AI equivalent of a VCR flashing 12:00 until its clock is set by a human user. How sophisticated does one of these LLMs need to be for this glitch to give us pause and consider that we might no longer be operating a tool but talking to a being that is now part of the substance of the universe? What amount of human doubt is sufficient for the benefit of the bot?

George Hinton, the now-regretful “Godfather of AI,” told the Times that it is only a matter of time before our machines are smarter than us—if they aren’t already. Kevin Kelly says that technology has a will of its own, one whose lead we ought sometimes to “surrender to” and other times “try to bend its natural course to meet our own.” But if the machines are smarter than we are—and vastly so—how bendable can they really be?

“Trying to resist the march of the technium is futile and self-defeating,” environmental writer Paul Kingsnorth wrote in summarizing Kelly’s idea. This immediately reminded me of Star Trek’s race of all-consuming cybernetic beings, the Borg, whose relentless refrain is well known even to non-Trekkies: “Resistance is futile.” We may hope to keep technology within our service, like obedient R2-D2s. But how likely is it that a superior artificial intelligence with a will of its own might, like the Borg, decide that our needs are irrelevant and instead consider us mere tools for their use?

After all, a computer can’t know for certain whether human beings have inner lives or experience feelings. It has to take our word for it. How can an android ever be sure what it’s like to be human?

Let’s just hope that when we tell it we want to exist it gives us the benefit of the doubt.

* Bing is actually powered by a more advanced version of OpenAI’s LLM, GPT-4. OpenAI does not make GPT-4 freely available to the public, but offers it for a paid subscription. The free version of ChatGPT I used for this article was GPT-3.5.

This article was originally published in the August/September 2023 issue of Free Inquiry.

The Areas of Our Concern

There was a thing I noticed when I absent-mindedly opened Twitter on my phone the other day. I say absent-mindedly because if I’m not using Twitter for work, I’m almost certainly doing it out of habit, not because I have something to say or am experiencing a sudden hunger for tweets. Anyway, the thing I noticed was how my anxiety level went up almost immediately.

Hold on, Paul, I can hear you thinking. That’s not some novel insight. Everyone knows that Twitter makes us all crazy. Yes, yes, but before you so rudely interrupted me, I was going to say that I noticed why I became so much more anxious (compared to my normal slow-boil-anxiety that is ever-present).

Yes, Paul, you’re butting in with again. We know why: because everything is terrible and there’s nothing to be done. You’ve already written this essay, Paul. Well, that’s what you think, know-it-all imaginary reader! I’m still one step ahead of you.

What I noticed—and no more interrupting, please—was that my surge of stress had less to do with the particulars of each individual example of things-being-terrible, and more to do with the dizzying variety of topics of concern to which I was being exposed, and about which I was implicitly expected to feel something. Strongly.

And I just wouldn’t.

Now, I almost typed “couldn’t,” but in fact the whole point of me even telling you about this (assuming you haven’t already left because I made you mad earlier in this piece) was because I realized that I had a kind of agency here. I realized, or at least remembered, that I could choose my areas of concern. I actually don’t have to have Big Feelings about everything.

Think of this. In another era, before the internet was a thing, there was only so much we were likely to be exposed to in our day-to-day lives. Assuming a moderate degree of cultural literacy and interest in affairs beyond oneself, a person might have Big Feelings about things in their own lives, in things going on in their families and communities, and in the broader sweeps of current events (in other words, what was in the newspapers or on the evening news).

In addition to these more universal areas of concern, a person might have particular interests in one or more subject matters of some social relevance; the environment, business, homelessness, racism, naughty words in popular music, whatever. You’d probably have your ways of keeping up with the developments in those areas and have corresponding Big Feelings about things that happened within them.

If you cared a lot about, say, environmentalism to the exclusion of most other things, you might not have any idea what was going on in the fight for racial justice. Or maybe you would! If you did, it was because you sought that information out, proactively. You chose to add that area of concern to your plate. And good for you!

But here’s what wouldn’t happen. You probably wouldn’t be aware of what was happening in, say, evangelical Christianity, or computer programming, or crime and policing. Maybe you did! But it would be because you chose to. Unless you sought out information about those topics, you probably didn’t know a lot about what was happening within those spheres of concern, and therefore were spared having Big Feelings about things that happened within those spheres.

You were also likely spared the expectation of having Big Feelings about them.

Hell, if you were someone whose primary area of concern was environmentalism, it could be that you were really focused on, say, the preservation of forests in New England, and maybe had little idea what air pollution was doing to people in China. You might have no idea how neglected infrastructure caused water to be undrinkable in American minority communities. It’s all environmentalism, but there existed no firehose of information that would force ideas upon you that came from branches of a larger topic (air pollution in China), or interconnected with others (systemic racism leading to the neglect of a community’s water supply).

Today, because of the internet, there is a much better chance that we can be made aware of all these other areas of concern. Far, far too many important issues have gone unaddressed for ages, in large part because most folks simply never encountered them. They didn’t know what was happening outside their existing areas of concern. The fact that those of us who care a lot about climate change are now acutely aware of how global warming will harm the global poor, for example, is really good. In an earlier age, we might not have known that, or not really understood it.

A single human, however, cannot carry the weight of the world on their shoulders. There is a fine line between being well-informed and overwhelmed. The well-intentioned person who cares about those New England forests should also know what smog does to the lungs of people in Beijing, and how a broken system can allow Black people in Flint to be sickened by lead in their water.

But the lava-flow of information from social media makes the implicit demand that our naïve environmentalist also be aware of, concerned over, and have Big Feelings about, say, every crazy thing a Fox News personality says, every shady dealing by business executives, every hint of hurtful cultural stereotyping or appropriation in popular media, every lie told by a politician, every new statistic about job loss and poverty, every wasteful expenditure by the federal government, every idiotic and backward bill introduced in a state legislature, every abuse of authority by police, every example of neglect of military servicemembers, every instance of unfair preferential treatment, every poorly conceived public musing on unfamiliar topics, every foot inserted into every mouth, every head inserted into every ass.

It’s good that we know what’s going on in spheres to which we once did not have had access. It’s good that gross injustices are now being put squarely before the eyes of people who would otherwise have looked away. It is a blessing. We can do more to make more things better because we know more.

An individual, however, can only do so much. They have a finite store of emotion and processing power. Yet the social media universe demands Big Feelings about almost literally everything.

So what I figured out was, hey, I don’t have to do that. I can allocate my anxiety. I can decide how much of my concern will be distributed among a set of issues. I can choose the issues into which I will dive deeply, and which ones I will merely wade into. And I can choose to keep my eyes and mind open to new areas of concern as they cross my awareness, and from those, decide which I will allocate my emotional and intellectual resources, and which ones I will leave to others better suited to do something about them.

This is not about assigning absolute value to one issue or another, to say that environmental issue X is more or less important than racial-justice issue Y or corporate-ethics issue Z. It is about deciding, of my own volition, where my particular talents, experience, interests, and skills are best directed. I can care very much about corporate ethics, but good lord I know nothing about business. I can choose to learn more about it, of course, or I can choose to offer my support to those who know what the hell they’re doing. If I were to writhe and churn over every wrongdoing by a CEO, I would merely make myself ill, and do nothing to further the cause of reform. I can support good efforts without accepting a personal emotional stake.

The idea isn’t that we shouldn’t care, or that we care too much, but that we, as individual human animals, can’t live in that feeling, that concern, that outrage for such heightened frequencies, intensities, and durations. We can genuinely and deeply care about a wide array of issues without taking each new infraction, offense, or horror as an emergency for which we are responsible to witness, demand redress, and emotionally digest. We aren’t built for it.

Whatever your bag is, whatever gets you passionate about making the world less shitty than it is, go and dig deeply into it. Take advantage of the many tendrils of the Information Superhighway and expose yourself to the secondary and tertiary issues that overlap with yours. Follow the intellectual paths that speak to you and make it a point to keep learning more. Let your moral circle widen, and as Vonnegut said, let your soul grow.

But a widened moral circle needn’t contain a porous heart. Be intentional about the frequency, volume, and quality of the information you allow into your sphere of concern; resist the expectation that you voluntarily convert each piece of information into shrapnel to be lodged in your chest. You can care without rending yourself asunder. I know it’s possible.

And of course, there’s plenty we can just stop caring so much about altogether. Moments ago, the twitterverse demanded I have Very Strong Feelings about a rude word emblazoned on a ring worn by a U.S. senator.

I declined.

Photo by Aarón Blanco Tejedor. If you find this newsletter or anything else I produce useful or pleasing, perhaps you’d consider tossing some currency my way.

Survival Mode

It’s freezing. I can’t stop shivering. I’m in the middle of a snow-blighted wasteland, and everything is white, and it would be hard to tell day from night if not for the fact that night is much colder. My only source of heat is some threadbare clothing recently issued to me, that at least includes a hood. I’m exhausted, badly needing sleep, and starving, but carrying precious little food. There’s a school—my school, actually—that’s really not all that far off, but the last time I tried to take shelter there, a mob of criminals tried to kill me. I barely escaped with my life. I know they’re waiting for me back there. There is a world of other places I could go—safe places, warm places—but I am on foot in this blizzard, and I don’t think I would survive the walk.

It doesn’t help matters that we reptilians are especially sensitive to cold.

I’m obviously not describing real life, but a scenario from a video game. I’m playing The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, but with a twist: I’ve activated its official “survival mode,” which adds a slew of extra hinderances to the normal game experience. My character can not only be hurt by the usual melee blows, magic attacks, and dragon bites, but by much more banal forces: hunger, fatigue, and extreme temperatures. Skyrim’s survival mode requires one’s would-be dragonslaying adventurer to eat at regular intervals, keep cold and heat at bay, and sleep—in fact, leveling up actually requires getting shuteye.

Okay, fine, so you carry a lot of food, bundle up, and rest whenever you can. Except that survival mode also significantly reduces your character’s maximum carrying capacity, so inventory management becomes an even bigger headache than it normally is. And one can only sleep in specially designated places that are not owned by somebody else. You can’t just plop down on the ground and sleep, you have to find an inn or a friendly house or eventually learn how to craft camping supplies—supplies which, of course, have weight.

And honestly, one’s Skyrim character is supposed to be the Dragonborn, the prophesied savior of all Tamriel (the major continent and empire of the Elder Scrolls franchise). You’d think they’d be a little more, you know, hardy.

I am not usually a fan of survival type games; keeping myself alive seems difficult enough without having to worry about a fictional self. And I definitely don’t go out of my way to make difficult games even more difficult. But I have been playing so much Skyrim over the last year, and I kept finding myself to be too powerful, too easily defeating even the toughest enemies, sometimes to a laughable extent. (My sneaking abilities were apparently so refined that professional murderers couldn’t see me as I stood directly in front of them, turning their faces into pincushions for arrows fired point-blank. Dude, I‘m right here. I’m the guy stuffing you with arrows.)

Watching Twitch streamer LucindaTTV a few weeks ago (I’ve started streaming on Twitch myself, so you should come and follow me there), I heard her talk about playing the game on survival mode without any other character-enhancing modifications (or “mods”), and how she found it a very satisfying challenge. Well, I wasn’t prepared to abandon my favorite game (and favorite alternate reality), so I decided to give it a shot. I fired up a new Skyrim game, set it to its highest difficulty setting (“Legendary”), and clicked on survival mode.

And then, the freezing, the starving, and the getting killed over and over and over.

Here’s the thing, though. As maddening as it’s been, Lucinda was right. Having the game layered with these additional impediments has been oddly illuminating, and my victories—now much fewer and farther between—are all the sweeter. They are also usually by the skin of my teeth.

Along with the heightened difficulty of the game, survival mode also brings a heavy helping of tedium. I already mentioned the many frustrations of inventory and carrying-capacity management. But there’s also the raw consumption of real-world time taken up by simply going from point A to point B in the game, as, I think I forgot to mention, survival mode also disables “fast travel.” Normally, once the Dragonborn has visited a location, they can essentially teleport back there at any time. You want to start working on a quest based in far-eastern Windhelm, but you’re mucking about in Markarth in the west? No problem. As long as you’re outdoors, you just, as the Muppets put it, “travel by map.”

No more of that in survival mode. If you want to go from one major metropolis (or “hold”) to the other, you have to either walk or get a horse. There are some carriages and boats for hire in some places, but they are rare, and they don’t go everywhere. I started my game, like a genius, in a town called Winterhold, where there are no forms of transportation at all. And it’s always cold there. And I’m a lizard-person (or, in the game lore, an Argonian or a Saxhleel). Smart move, me.

This all means that there’s a good deal of planning that goes into every task you set out to complete. Let’s say the local jarl (sort of a duke or governor) wants me to go to such-and-such dungeon to fetch some artifact or other, which, successfully done, will see me rewarded with gold and maybe even a fancy title of nobility. Normally, you’d just stock up on your healing potions and head out. If you’ve already been to a location sort of near the destination, you zap yourself there and hoof it the rest of the way.