essays

Suicides Are Not Car Accidents

When trying to make a point about the troubling rise of suicide rates in America, the statistics are often compared to other modes of fatalities, and understandably so. In order to understand the scale of the problem, it helps to compare it quantitatively to undesirable things we feel more familiar with. But in the case of suicide, I think it diminishes the scope and seriousness of the issue.

I’ll pick on Arthur C. Brooks’s column at the Washington Post, because that’s what got me thinking about this. Brooks rightfully urges a serious confrontation of the undeniably sharp and steady rise in suicide rates, and to convey just how bad things have gotten, he draws comparisons to homicides and motor vehicle accidents. According to his cited statistics, there are now two suicides for every homicide in America, and there are 17 percent more deaths per year by suicide than by car accidents.

While these numbers do help to communicate the scale of the problem, these kinds of comparisons, to my mind, oversimplify the issue to an unacceptable degree and make some morally false equivalencies between only somewhat related actions and phenomena.

Let’s start with the homicide-suicide comparison, and take as granted that twice as many people die by suicide than by homicide. Put aside for the moment the rise in suicide rates. Is the fact that more people take their own lives than have their lives taken from them in itself an obviously bad thing? In every instance? Could it not be a sign that perhaps we are now less eager to murder each other, and that if we must die by someone’s hands, at least it’s more likely to happen by our own choice and volition rather than someone else’s?

Of course it’s not “a good thing” that people want to kill themselves, but what does it actually mean to point out that there are more suicides than homicides? One is a death without choice, the other, at least in the broadest sense, is. What this numerical comparison ignores is what drives a person to make that choice. Would we feel better if those numbers were reversed? I don’t think I’d feel very safe if I was told that I was twice as likely to die by murder versus suicide.

Now let’s look at the comparison to death by motor vehicle accidents. It’s similarly problematic, in that it is not at all clear to me that we’d be pleased to see the statistics in reverse, in which car accident fatalities overtake suicide deaths. In that case, we’d all be wondering what is up with all the careless driving and poorly-made vehicles?

More to the point, Brooks points to the campaigns of a generation ago to improve car safety and how they eventually led to laws and regulations that made cars and driving much safer than they had ever been, and says, essentially, let’s do that, but for suicide.

This makes little sense to me. Absolutely increase public awareness of the issue. Countless people might be helped if more Americans were better educated and empathetic about suicide. But what else are we really talking about? There’s no suicide equivalent to seat belt laws, speed limits, or air bags.

Auto accidents, and to a lesser extent homicides, are more or less binary. They are bad things that result in unwanted deaths, but they can be prevented and mitigated by a fairly straightforward collection of measures. Make cars safer, make guns scarcer, and so on. Homicide is somewhat different in that, like suicide, its tendrils reach much deeper into other societal ills, and I’ll address that in a moment. But both auto accidents and homicides boil down to one thing: They kill people who don’t want to be dead.

Suicide is something else entirely. Let us grant for the sake of simplicity that no one’s starting position is “I want to be dead, and I want it badly enough that I will end my own life myself.” Something has to push a person into that place. Several somethings, both apparent and invisible. Whatever those factors are, they are different for everyone. I’m not even slightly qualified to list them or assign them relative values. But you know some of them; depression, fear, hopelessness, self-loathing, brought on because of abuse, joblessness, loss, addiction, and so on.

The point is that while murders and car crashes steal a person’s life from them, in the case of suicide, something else has stolen a person’s desire to live, and, importantly, driven them to the point that they have concluded that ending their life would be preferable to living it. Even if we could install some sort of air-bag-for-suicides and prevent the vast majority of them from succeeding, we’d certainly bring the suicide numbers down, but we’d have done nothing to address what brought on the choice to try in the first place. There’d be fewer deaths, but just as many miserable people.

So the question can’t be — must not be — “how do we bring down the number of suicides?” The real question is about how we change society so that tens of thousands of people every year do not become so overwhelmed by existential despair that suicide even becomes an option worth considering. Yes, that means laws, but not just preventative laws focused on the act of suicide itself. If that’s all we’re thinking about, then we’re too late anyway. But we will need laws that address poverty, economic anxieties, addiction, basic health and nutrition, mental illness, education, and much, much more.

But we’ll also need to change our culture, heart by heart. We’ll need to call ourselves to become kinder to each other, more sensitive to the pain of our fellow humans, and more willing to be a friend. We’ll need to stamp out those ideologies that thrive on the marginalization of other groups, and teach each other not to fear or resent equality. We have to decide, on an individual basis, to celebrate and embrace each single person’s differences and idiosyncrasies, and rather than seek uniformity, consider our species blessed by its infinite variety of neurologies, talents, flaws, ideas, histories, gifts, and limitations.

When we start to assign value to each and every one of us, then, maybe, we’ll see those suicide numbers go down. Not because we managed to stop more folks from pulling triggers or popping pills, but because far more of us have decided that this world is worth living in for as long as we can.

Forty-Two

Listen: There are things we are supposed to want out of life, and there are the means by which we are supposed to attain them. There are cultural events, life milestones, rites of passage, and personal interactions which we are supposed to eagerly anticipate, and those we are supposed to bemoan. There are standards of comportment we are supposed to uphold, degrees of amiability we are supposed to project, and durations of eye contact we are supposed to maintain.

We are supposed to know when to laugh and when not to laugh. We are supposed to stand a certain way and sit in a certain way, and ways in which we are not supposed to stand or sit. We are supposed to have street smarts, as opposed to book smarts, but we should have enough street smarts to know how to attain those book smarts. We are supposed to be honest, except when we aren’t supposed to be. We are supposed to be careful and we are supposed to take big risks.

We are supposed to have jobs and we are supposed to seek to advance in both position and compensation in these jobs. We are supposed to look forward to lunch. We are supposed to care a great deal about food and eating and sporting events and and acts of geographical transit and the weather. We are supposed to care a great deal about many, many things, and we are supposed to know what those are without being informed in advance.

I have lived my life riven by “suppostas.” From the very first moment I realized that the world had expectations of me beyond the routine of elementary school classrooms, I was in a state of near constant bewilderment as to how I should go about my existence. All rules were unspoken and yet somehow universally understood and viciously enforced. I never received instructions, only penalties for failing to follow them.

So I flailed about in search of guidance; examples to follow and role models to emulate. But I never found any templates that I could build upon, no maps I could interpret, no ciphers I could even attempt to break. In day-to-day moments, there were ways to sit, to stand, to walk, to move, or not move, and I coudn’t make sense of them, which often meant defaulting to keeping very still. In my education, there were crucial tasks to accomplish that had nothing to do with that was in the syllubus, and yet were somehow clear to my peers. In the professional world, the litany of unwritten rules, agendas, rites, and rituals were so perplexing and numerous that it caused a kind of paralysis.

From the quotidian to the global, I simply could not figure out how to be. How I was supposed to be.

The problem may already be obvious to you. My error has been to seek meaning and validation through my perceptions of what other people value. I don’t know how I could have known any better. To observe other humans is to see them behave based on some combination of motivations that are invisible to me, guided by some set of rules that is equally inaccessible. Existing, as I do, as a single individual with no way to read the contents of anyone else’s thoughts, all I can do is look and guess, like trying to describe the constellations in the night sky by looking through a paper towel tube.

I would be 38 by the time I realized why the behavior of my fellow humans baffled me so, and why I was so lost navigating this ocean of “suppostas,” for that’s when I was diagnosed with Asperger's syndrome, when I found out I am autistic. One aspect of this neurological difference is difficulty with ascribing agency to other people. Another is difficulty deciphering, or even perceiving, nonverbal communication. There are many more parts to being among the neurodivergent, but it all boils down to this: I don’t think or behave the way everyone else does, and I have a lot of trouble understanding what is happening around me if it’s not being explicitly stated. I have a neurological supposta deficit.

But forget that. Placing too much value on external validation is not solely the burden of autistics. Being baffled by the motivations and behavior of other people isn’t exclusive to the neurodivergent. We austistics are more likely to face these kinds of difficulties, often to greater degrees of severity, but feeling misunderstood or alienated is part of being human. We all fear being lost or alienated.

We can’t just dismiss this phenomenon as an error in thinking and move along, though. Whether or not we’ve identified the error, we still have the underlying problem, which is, really, how are we supposed to have meaning in our lives? How are we supposed to matter?

I think I have looked to others to tell me what is meaningful because I couldn’t work it out for myself analytically. When I think about the whole life-cycle trip we’re all taking down this mortal coil, it looks like this: We’re born ignorant and helpless, and starting from absolute zero we then spend twenty-odd years learning how to be a human in the world, and then spend what time we have left deteriorating until we eventually expire and utterly cease to exist at all. Good lord, what, I ask you, is the point?

Given that it looks so plainly like there is no point, and that existence has no meaning, the anxious young mind eagerly looks to the example of others. What’s meaningful to them? To what ends to they direct their finite time and energy? What do they celebrate and what do they revile? In short, what do they value? I hoped that by aping the moves of the humans around me, I would know what I was supposed to value.

This was never going to work.

Of course, society at large will always, at the least, set up the guardrails for what we find meaningful about life. We all learn by example from our family, our peers, and our broader culture. None of us find meaning in a vacuum.

What I didn’t realize, and what I think many people don’t realize, is that there is no meaning there to be found. Those expectations that society places on us, or that we place on ourselves, those “suppostas,” can nudge us in one direction or another or, hopefully, keep us from finding meaning in the grotesque or destructive.

Meaning itself, however, is not something that anyone or anything can provide or even define. In The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, the supercomputer Deep Thought is built in order to answer the great question of Life, the Universe, and Everything. Famously, after millions of years of calculations, Deep Thought declares the answer to be 42, which of course makes no sense to its egregiously disappointed audience. Obviously, the Answer is supposed to have a Question, so it builds another, even more unfathomably advanced computer to figure out what the question is that would spit out the cryptic answer 42. More hilarity ensues.

The first (several) times I read that book, I took it as I suspect most people did, as a wonderful example of humor, literary cleverness, misdirection, and a great poke in the eye to know-it-alls everywhere. And it is all of those things. But only now, at this point in my life, do I actually get it.

As a miserable, alienated, and frightened pre-adolescent, terrified of each new school day, I would have given anything to have a Deep Thought of my own to tell me What The Hell It Was All About. Throughout my adulthood, even with whatever wisdom I had accumulated, I would have no less welcomed an algorithmic answer to Life, the Universe, and Everything. But it doesn’t exist. It can’t exist.

In recent years, coming closer to terms with who I am has allowed me the psychic space to better appreciate those things that do not fit into a formula for optimal meaning generation. An atheist and skeptic through and through, I have yet developed warmer feelings toward practices and frames of mind that are usually the domain of religion. I don’t need to believe in the literal existence of supernatural beings in order to find peace, connection, or motivation through ritual and story. I am developing a love for the numinous and the immeasurable.

Ritual, for me, can come in the form of artistic creation. Writing essays like this is a kind of prayer or meditation, allowing me to have a conversation with myself, to interrogate and beseach my own mind for insight. Making theatre is not unlike having a church, where great stories are told by a congregation of participants in order to be shared and experienced by the community. Indeed, theatre and religion are siblings, both born from the stories told by our earliest ancestors around the fire.

These things are not, in and of themselves, meaning. Theatre may have an effect on me that is akin to “spiritual,” and I might just really like doing it, but that’s not what makes it meaningful. It’s not even enough to say that something in my life has meaning because I have chosen to bestow meaning upon it. Really, it’s the fact that I’m not at all sure that it has any meaning at all. Or that anything does.

For our lives to matter, and for what we do to have meaning, we have to endow it with meaning ourselves. But, remember, in the sense of some core, cosmic truth, meaning does not exist. So for me to bestow meaning on something is the same as my granting myself a knighthood. I can do all the bestowing I want, but it doesn’t make it so.

The point, then, is not to discover meaning. The point is to look for it. It’s the search, the investigation, and yes, the agonizing doubt. There are precious few creatures living, that we know of, that are blessed, or cursed, with the ability to even engage in this kind of inquiry. It is a quest to satisfy a yearning for that which can never truly be had.

And there is no single way one is supposed to go about it. “Suppostas” are meaning-repellents.

I was about 10 years old when I realized I was something of an alien among other humans. After college, a dear friend of mine told me I’d figure myself out by age 27, and that didn’t happen. At age 41, still fresh off of an autism diagnosis and a divorce, I looked at an actuarial table that showed that I was at the precise midpoint of my lifespan. Barring unfortunate events, I had lived the first half of my life. A few weeks ago, I stepped into the second half.

Maybe it’s age. Maybe I’m just too old at this point in my life to care anymore what people think of me. Maybe it’s not the result of personal enlightenment, but that I simply no longer have the energy to care. Or maybe being fatigued by all the pretending, all the masking, all the passing as “normal,” maybe that very exhaustion is what has allowed for clarity. I just know that my life is likely more than half over, and I’m tired of the suppostas.

I no longer want to fit in. I want everyone else to make room.

So now I actively combat my old instinct to worry about what it is I’m supposed to be like. It is a daily battle, but at least now I’m waging it. Now I am more interested in that yearning, the endless inquiry into meaning and mystery. And I often feel frustrated by the lack of solid answers and despairing of my failures, but I can also accept that the frustration and despair are themselves part of the story, as much as anything else.

It turns out the question was always the answer. And it just so happened that I would arrive at this understanding at this particular time in my life. So, in a way, the answer was, in fact, 42.

A New World Without Loss

Arthur C. Brooks writes about how Ludwig van Beethoven dealt with his gradual hearing loss, which, while crushing to a genius composer, ultimately lead him to new heights of greatness.

It seems a mystery that Beethoven became more original and brilliant as a composer in inverse proportion to his ability to hear his own — and others’ — music. But maybe it isn’t so surprising. As his hearing deteriorated, he was less influenced by the prevailing compositional fashions, and more by the musical structures forming inside his own head. His early work is pleasantly reminiscent of his early instructor, the hugely popular Josef Haydn. Beethoven’s later work became so original that he was, and is, regarded as the father of music’s romantic period. “He opened up a new world in music,” said French romantic master Hector Berlioz. “Beethoven is not human.”Brooks takes this as a lesson in loss. He says that here Beethoven shows us how losing something precious can open up new possibilities and ideas, and all of that is true. But that’s not the lesson I take.

When Beethoven lost his hearing, he could no longer be aware of what others in his field were doing. Whatever music was being lauded or pilloried at the time, Beethoven had no way to know what it sounded like. He had no way to compare his work to anyone else’s. All he had were his memories of what had come before.

To me, the lesson isn’t how Beethoven turned the tables on fortune and made something beautiful out of loss. (And I do have my own, albeit far less severe, experience of hearing loss to draw from here.) The lesson is that his loss meant that he was no longer burdened with his own perception of what great music is supposed to be. Beyond what he could still hear in his own mind from his musical memory banks, there was nothing for Beethoven to compare himself to. The energy spent and wasted on anxiety and self-doubt brought on by the desire to suit the tastes of the time, his genius was liberated, freeing him to make the best music he was capable of at that moment.

Before I sat down to write this, I caught myself wondering whether the traditional early-2000s-era blog format was still viable, whether anyone would want to read a post by a relative nobody responding to an article by a relative somebody about an indisputably significant somebody. I worried whether the format would make me seem unhip. I worried that whatever I wrote might better suit a magazine essay, which would never be written (nor published if it were), or if it might be best to simply tweet a condensed version of my thoughts, and leave it at that. In other words, I wasted time and energy on anxiety about what my writing is “supposed” to look like.

Imagine that I came to this piece with no preconceived notions of the form my thoughts should take. Imagine I had no respectable essays, eye-catching blog posts, or pithy tweets to compare myself to. Imagine that all I had were my thoughts and my skills as a writer, whatever they happened to be at this moment.

Beethoven’s loss forced him into a position of ignorance. His deafness gave him no choice, but that ignorance freed him. His earlier work sounded like somebody else’s, the work of people he thought were “doing it right.” When he could hear no one else, “doing it right” meant only what was right to him in his own mind.

I, and we, do not have to wait for loss. We do not have to be forced into a kind of ignorance. We can choose to learn from what others have done, build on what we have already accomplished ourselves, and then let everything go. Then we can be free, and we can know it, too. We can open up a new world without loss.

Beethoven is not human, and neither am I. Thank god.

Purposeless on Purpose

I seek to be at peace with my own irrelevance.

In earlier, less distracted, and less accountable years, I was a fount of creative energy. Free time was often spent on writing songs and recording music or writing essays and blogs. I have always been driven to create. That drive formed my earliest sense of identity.

Today, in my forties, raising two kids, and working at an intellectually demanding job, my sparse remaining energy usually feels insufficient for extracurricular creativity. Fumes make for a poor muse.

So I don’t write nearly as much anymore. I rarely pick up an instrument. Songwriting is now filed away in the dusty archives of my persona as ”something I used to do.”

But while the fatigue of existence is real, and my drive to create fires on fewer cylinders, these aren’t the real obstacles to creating. Nor can I lay the blame on the easy abundance of distractions provided by the internet, a phenomenon that had yet to saturate the culture when I was in my prolific twenties.

It used to be that as I worked, with every paragraph or stanza, I believed myself to be building toward something. I was laying the foundations of my career, one in which I would not just be a creator, but one that mattered. “Fame” isn’t quite the right word for what I was after (though I would not have shunned it by any means), but perhaps “prominence.” I would be known.

That didn’t happen. It’s not going to happen, either. For years now, this has been an inexhaustible source of regret and self-loathing. I’ve been dedicating a great deal of thought and work toward being at peace with the fact that whatever meager level of renown I’ve scraped together at this point is about as good as it’s ever going to get.

What does this mean for the creative drive I claim to still possess? Nothing good, I’ll tell you that!

I might become more accepting of my irrelevance to the wider world, but that very acceptance starves me of much of what once served as creative fuel. Why write an essay that only a handful of people will ever read, for which I will not be compensated, and which doesn’t lead to my work being discovered so that I can be placed into the demi-pantheon of People Whose Writing Matters?

In other words, why bother?

The wall of “why bother” is a big one. From any distance, its summit visibly looms over the top of my laptop’s screen. Large, white letters adorn the wall like the Hollywood sign promising “NO ONE CARES.” The letters are much brighter than the display on which I type.

One is not supposed to see things this way. Creation is supposed to be for its own sake. I have always had a great deal of trouble with “supposed to’s.”

So I seek out wisdom. In Zen and the Art of Archery, Eugen Herrigel questions his master about the purpose of his archery training. The master insists that Herrigel take no note of the target. The master insists that he not consider releasing the arrow. For what feels like ages, the master keeps him focused only on drawing back the bow, and nothing else. And Herrigel is utterly flustered. He says to his master that he is unable to lose sight of the fact that he draws the bow and lets loose the arrow in order to hit a target. There is a reason for all of this effort:

“The right art,” cried the Master, “is purposeless, aimless! The more obstinately you try to learn how to shoot the arrow for the sake of hitting the goal, the less you will succeed in the one and the further the other will recede.”They debate this point for a bit, and Herrigel asks:

“What must I do, then?”The idea that art, creation, is purposeless, is very difficult for me to internalize. I can intellectually understand and even appreciate it, but I can’t seem to accept it in my heart. The words “why bother” still ring in my head, and the “NO ONE CARES” sign still leaves a visual trace on my retinas when I close my eyes.“You must learn to wait properly.”

“And how does one learn that?”

“By letting go of yourself, leaving yourself and everything yours behind you so decisively that nothing more is left of you but a purposeless tension.”

“So I must become purposeless — on purpose?” I heard myself say.

“No pupil has ever asked me that, so I don’t know the right answer.”

“You will be somebody, the second you make peace with being nobody,” Heather Havrilesky has written. “You can create great things, the second you recognize that making misshapen, stupid, pointless things isn’t just part of the process of achieving greatness, it is greatness itself.”

Being purposeless on purpose is, itself, greatness? I want to believe. The idea that a creative work is supposed to be purposeless is a claim without evidence. It is less a truth than it is a statement of faith. One has to decide for oneself that the work itself is enough.

“Let go of the shiny, successful, famous human inside your head,” writes Havrilesky. “Be who you are right now. That is how it feels to arrive. That is how it feels to matter.”

I do believe that. I can work with that.

But she also says, “Being a true artist merely lies in recognizing that you already matter.” That, I don’t understand. How does she know what qualifies one as a true artist? How does the archery master know that one’s aim must be aimless?

Like many statements of faith, I suspect the value of the claim that art is purposeless lies less in its veracity, and more in the behavior it induces. Its value is in the discipline required to live that ideal. It may or may not be true that creative work is “supposed to” be purposeless. It may or may not be true that writing this essay right now, or any other, is a meaningful end in itself, regardless of whether it is ever read or appreciated by anyone.

I don’t know if these things are true. I doubt that they are. But I might need to take the leap of faith and live as though they are. Doing so will take a good deal of practice. Discipline. But unlike art, it would not be purposeless. For if I can manage it, I may begin to believe that I do matter right now, and that mattering right now, and at no other time nor to any other people, is enough.

In Between the Pictures is the Dance

I’m not a dancer by any stretch of the imagination, but I’ve taken my share of dance and movement classes in my previous life as an acting student. I don’t mind being able to tell people that “I studied dance at Alvin Ailey,” which is technically true, as that’s where the acting students in the Actors Studio graduate program had dance classes. I was a hard-working if mostly-hopeless student, and a frequent cause of eye-rolling and pity-sighs from our teacher Rodni, who moved with incredible control, strength, specificity, and power. It was not necessarily transferable.

I’m not a dancer by any stretch of the imagination, but I’ve taken my share of dance and movement classes in my previous life as an acting student. I don’t mind being able to tell people that “I studied dance at Alvin Ailey,” which is technically true, as that’s where the acting students in the Actors Studio graduate program had dance classes. I was a hard-working if mostly-hopeless student, and a frequent cause of eye-rolling and pity-sighs from our teacher Rodni, who moved with incredible control, strength, specificity, and power. It was not necessarily transferable.

The man who taught me more about dance and movement than anyone else in my life was Henry, the impossibly graceful, endlessly wise, and astoundingly patient head of the dance department at my undergraduate state college. Truly, there was something superhuman about the man (I assume there still is, he’s alive and well, and I imagine will be for many centuries to come). Taking a dance class with Henry was what I imagine taking a physics class with a gifted professor is like; it seemed as though every lesson had several “ah-ha” moments in which something marvelous about the body in space suddenly broke its way into my bewildered brain.

An example: What is walking? Henry would ask us as we ambled around the studio. The answer, which I was distinctly proud to call out in class when I had my eureka moment: Walking is falling. Think about it, you’ll get it.

Getting through to me was a doubly remarkable feat on Henry’s part, given that I’m autistic (Asperger’s, to be precise), which was unknown to me at the time, and surely made the job of teaching me how to move in a coordinated, graceful way exceedingly difficult. Rodni, gifted as he was, could have learned a few things from Henry, I have no doubt.

One particular “ah-ha” moment with Henry came outside of regular class time, when for some reason I can’t recall, he was looking over some of the choreography he had written for the school’s next big dance concert. I had never seen choreography written down before, only taught to me in person (an experience I do not envy any choreographer). Musical notation I could understand conceptually, of course, but how could one codify movement in unmoving glyphs?

I don’t know what most choreographers do, but Henry’s approach was pretty damned simple: stick figures. Much like a comic strip, the figures would be drawn in particular poses, indicating the moves the dancers would execute at various points in the music. There were probably arrows indicating direction and other marginalia scribbled throughout, but this is all I can remember.

I think I expressed my surprise that this was how choreography was written, that it could be done with stationary pictures even though the art form itself is based entirely on motion. Henry explained that rather than think of them as representations of movement, each picture should be thought of as points for the dancer to reach, marks to hit with their bodies. The stick figure poses were guideposts, “You Are Here” indicators.

“The pictures are the choreography,” explained Henry. “In between the pictures is the dance.”

There’s that cliché about the journey being of greater value than the destination, “it’s not where you go, it’s how you get there,” and so on. Maxims on that theme are so overused that they usually come off as trite to me, if not meaningless, or at least what Daniel Dennett might call a “deepity,” an idea that is true on its face in the most basic and obvious way, but without any of the profundity it’s presumed to convey.

I may be coming around.

Another fellow who, though I’ve never met him, I nonetheless consider one of my most important teachers, is the writer Alan Jacobs. One of his recent books is a short volume called, simply, How to Think, and truly, I feel like no one should be allowed to discuss politics or religion, write opinion columns, or use Twitter until they’ve read it.

The book warrants a substantive review of its own, but I want to call attention to one passage that had my neurons firing off like the 1812 Overture. Thinking, according to Jacobs, is a skill that has been wrongly equated with coming up with answers, decisions, and responses. Thinking becomes about being right, about winning. Jacobs explains what it’s really about:

This is what thinking is: not the decision itself but what goes into the decision, the consideration, the assessment. It’s testing your own responses and weighing the available evidence; it’s grasping, as best you can and with all available and relevant senses, what is, and it’s also speculating, as carefully and responsibly as you can, about what might be. And it’s knowing when not to go it alone, and whom you should ask for help.

Decisions, answers, conclusions; these are the final pose at the end of the music before the curtain falls. Each new piece of data acquired, each bit of information learned, are marks to hit, the guideposts that lead us on. They are static snapshots, pictures. But the thinking itself is what happens while we’re seeking those data points, hunting for information, and piecing it all together in our minds.

In between the pictures is the dance.

A few months ago, a friend of mine fervently insisted I read Mark Manson’s The Subtle Art of Not Giving a Fuck, one of those anti-self-help books that seem to hip right now. I was somewhat reluctant. (Oooh, it has “fuck” in the title! How edgy!) But I am so glad I did, because, much to my surprise, it taught me what happiness is.

That’s overstating it somewhat. But Manson offers a way of thinking about happiness that, for whatever reason, had never consciously occurred to me. Simply put, Manson says that happiness is not a state one achieves, but it is rather a process, it is what we experience when we are solving the problems we want to be solving.

That’s it. Happiness is not something to be attained, it’s just what happens while we’re solving problems. If we hate or don’t care about a set of problems, we’re miserable. If we do care about them, the process of solving them is what makes for a rewarding, meaningful existence. If I am spending my time and energies on tasks that hold no meaning for me, I’ll hate every moment of it.

But when I’m directing a play for my university students, for example, I can actually experience bliss, because I’m solving the problems presented by the production so that it can become its own living, breathing work of art. When it’s over, and the run of the play has finished, I almost always crash hard, and have serious trouble clambering my way out of a serious depression. This is largely because completing the play is not what brings me happiness (though averting a disaster for the production also averts severe psychological breakdowns).

It’s putting the play together that brings me meaning; helping the actors understand what they’re saying and why their characters do what they do; arranging the movement and positions of bodies on stage; coming up with ideas for costumes, sets, props, and sound; helping individual students overcome their hangups and anxieties so that they can grow into their roles and blossom. While it’s gratifying when each problem gets solved, checking off boxes on the great beast of a to-do list that a theatre production can be, each solved problem is one mark, one picture.

The struggle is the point. The joy is in the journey. Happiness is in the process. And in between the pictures is the dance.

Am I too old to have just figured some of this out? Having spent 40 years obsessing over goals and products, I never noticed that everything that mattered was in the reaching, in the creating. The doing, not the having-done. The -ing’s, not the -ed’s. Looking back, it becomes obvious.

I have time left, I think. I hope. I can’t have those previous 40 years back, but maybe I can reframe my memory, tell my story to myself that focuses on the journeys rather than the successes and failures. And maybe I can start the next story from this perspective, though not as a goal to be achieved — I must think differently about my life— but as a process, a discipline, an asymptotic odyssey.

Look, some goals must be achieved, whether they provide meaning or not. Marks do have to be hit and some boxes absolutely have to be checked. You know what kind of box-checking I mean, the Maslovian, bottom-of-the-triangle kind, the kind that provide for one’s life necessities, and that of those in one’s care. There is not always joy in hitting the most remedial marks of mere survival. Though maybe there sometimes is.

This is how love works too, isn’t it? Whether familial, platonic, or romantic, it’s the active cultivation of a relationship, the choice to give of oneself to another person, be it a child, friend, or lover. Like happiness, love can’t just be a feeling, a state that we achieve, or a spell cast upon us. It’s the choice to love — a choice we keep making, moment to moment, picture to picture — that gives it meaning, that makes it matter, that makes it real.

I think that has to be it.

Walking is falling, and in between the pictures is the dance. I between the answers is the thinking. In between the giving is the love.

In between the moments, in between the events, in between the accomplishments, in between the failures, in between the losses, in between the lessons, the steps, the miles.

In between the seconds is life. That’s where it is.

Please Talk Me Out of It

Here’s what I need to know.

I need to know that all is not lost. I don’t need to be told that all is not lost, I need to be convinced. I need proof. Without that proof, I either have to remain in this unbearable state of stomach-churning anxiety, or I have to accept the end and prepare for what’s truly next to come.

So this post is a request. Or maybe a cry for help.

Let me go back a bit. I left my theatre career in order to get involved in politics, because I believed that the good I could do in that arena would be more tangibly meaningful than whatever effect I could have as an actor on a stage. (I was almost certainly wrong, but that’s for another post.)

When I made that decision, George W. Bush had been re-elected president, and as bleak as that was, I knew that there were enough souls in this country to nudge the ship of state in a more positive, enlightened, and humanitarian direction, if only they could be moved to do so.

While the Democratic Party wasn’t exactly doing wonders for itself during this era, it still had the allegiance of about half the electorate, and they managed that following not with aw-shucks faux-average joes or slick media manipulators, but with statesmen. People like Al Gore and John Kerry may not have been the most charismatic politicians, and lord knows they were prone to screw-ups. A lot of folks even doubted the sincerity of their principles, but I didn’t.

There is always ugliness in politics. There are always egos of unusual size and tenderness, always those whose ambitions for power boggle the average citizen, always undesirables and deplorables, even within the wider orbits of leaders and representatives on unquestioned integrity. It will always be so. This is a given.

I always understood the Republican Party to be premised on a lie, on the claim that it was made up of men (and almost entirely men) who stood for traditions, stability, and safety. The reality was and is of course that, as long as I’ve been alive, it has stood for the perpetual acquisition of power for those who already have it. Some within the party and its ancillary groups and movements truly believed in the values the party pretended to care about, and, as all of us are wont, managed to rationalize every ethically or morally repugnant action taken on the party’s behalf; from senseless wars to pandering to theocrats to stoking xenophobia, racism, and disgust for the already-marginalized to decimating the mechanisms of society on which tens of millions of souls rely.

Just as evil men could launch themselves into the orbits of true-hearted leaders of character, well-meaning people could also find themselves pulled by the gravity of this plutocratic gas giant, and therefore in its thrall.

I have taken this all as given. This darkness, this oligarch-trained leviathan disguised as an American political party, was known.

Yet I believed that if the Truth could be successfully and thoroughly conveyed, if the public could only be persuaded to listen and think for a half a moment longer than our lizard brains are inclined, and if the body politic could be exposed to just the right appeal to our innate empathy and higher notions of ourselves, then we could win. I was never so naive as to think that there could ever be anything like a total victory, one in which our politics reflects the loftiest ideations of what true democratic discourse could and ought to be. But I did believe that there were sufficient numbers of us who, given the right nudge, could look past our lazy, atavistic aversions and foster something approaching a national generosity of spirit.

Lost elections didn’t necessarily mean total defeat, either. If the good guys couldn’t quite make their case on one go around the electoral track, we regroup, rethink, and run the race again.

And when a brilliant, professorial black guy whose name rhymes with “Osama” gets elected president, twice, despite running against a lionized maverick war hero, and later a man who was clearly grown in a pod for the purpose of becoming president, I think it’s understandable that I could come to believe that not only could we win sometimes, but that the tide had finally turned. We were winning.

During the Obama years, despite the pride I took in knowing that a truly good man was president, it was impossible to ignore the boiling magma of fear and hate that began cracking the surface of the public sphere and spewing jets of scalding rage and idiocy, disfiguring all who wandered too closely. So too, it was impossible to ignore the depths of cynicism, callousness, hypocrisy, and mendacity that Republican leaders and cultists were willing to employ for even the tiniest gains, at the national, state, and local levels.

I knew it was there, and it made me sick, physically ill. And yet I still couldn’t allow myself to believe that it was indicative of more than a disgruntled ruling class and a baffled, aging demographic lashing out like a cornered animal. If nothing else, it would only be a couple of decades before these increasingly anarchic tribes of aggrieved aristocrats, and the ignorant mobs to whom they distributed pitchforks, would simply die off.

Now it’s 2018. Every branch of government is not only utterly dominated by Republicans, but by the very worst kinds of Republicans. The grotesque horror that is the president is well established, but he is only one part of a triumvirate of depravity.

There may be no one living who encapsulates the word “soulless” better than Mitch McConnell. With truly inhuman coldness, he lies, schemes, and destroys. I find him terrifying.

Paul Ryan is a tool. If Republicans keep hold of the House, Kevin McCarthy will be a stupider tool. Less principled than Ryan, if that’s even possible, and without all those pesky brains to confuse matters. And the House Republicans themselves are not much better than the most conspiracy-crazed Tea Party rally, only wearing suits instead of eagle-emblazoned tank tops.

And there’s the latest tragedy, the courts. Among a Supreme Court conservative majority largely made up of partisan hacks, Brett Kavanaugh has asked America to hold his beer(s) as he proceeds to out-hack them all. He is the Platonic ideal of the aggrieved, old, rich, white guy, a Euclidean avatar of the spoiled, entitled country-clubber, who now feels that he has been wronged by Democrats and, more importantly, American women, who dared to question his right to their bodies. Well, now he gets to show them who’s boss.

Let’s not stop there! In state after state, legislatures and governors conspire to dismantle democracy itself. From the disenfranchisement of minorities and the poor to the revocation of municipalities’ right to local governance, Republicans are torching the fields and salting the soil.

If we’ve learned nothing else from the past decade, it’s that if Republicans can’t win through persuasion, they’ll simply rewrite the rules. They control Boardwalk and Park Place perpetually. It’s written right on the inside of the box, that they shall eternally passeth Go, over and over, forever and ever, amen.

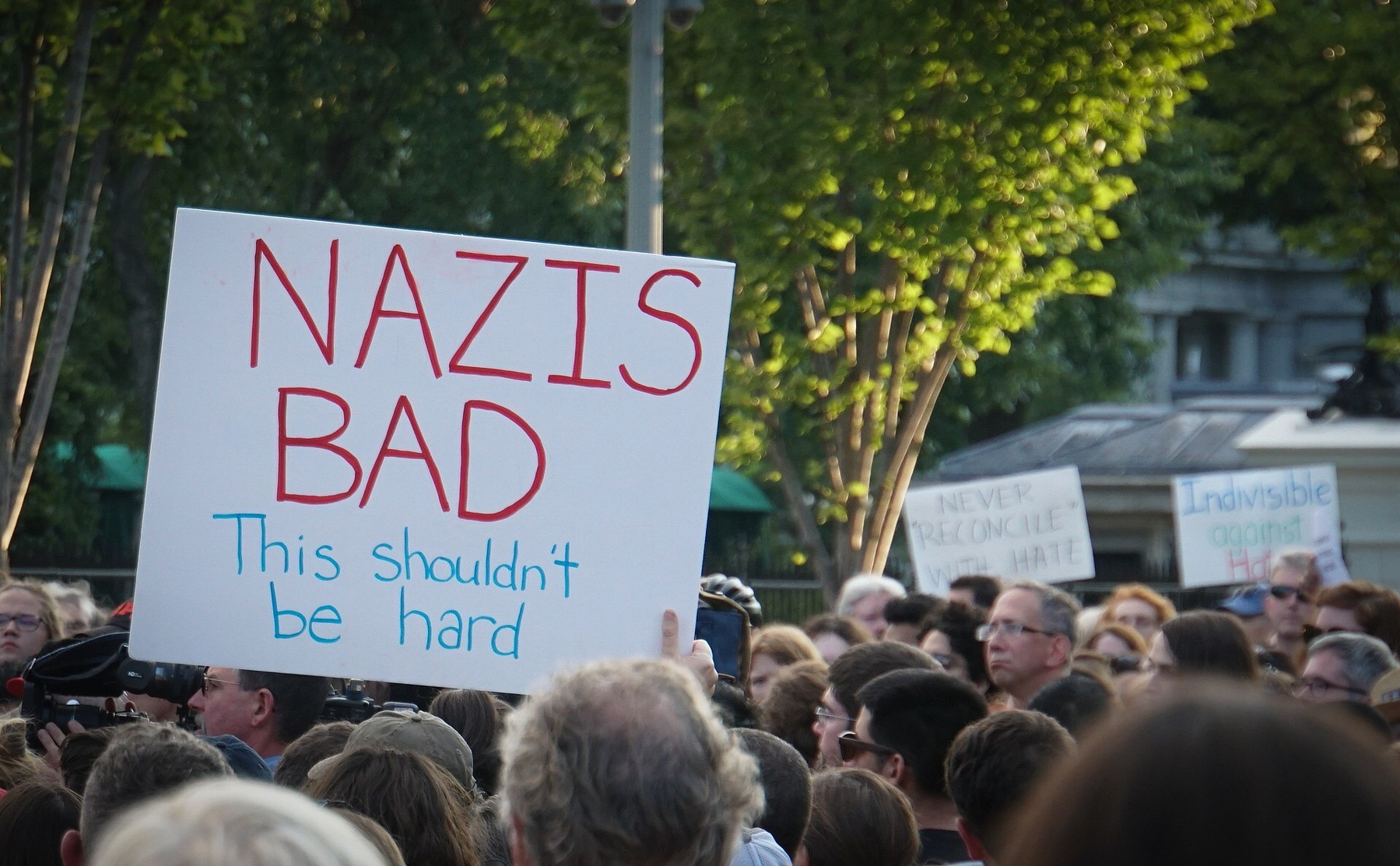

Today, those of us in the reality-based community, those of us who aspire to something more meaningful than personal power or status, those of us who feel a whit of empathy for those unlike ourselves, are scared. We are marching, we are rallying, we are donating time, money, and energy. We are sparking vital social movements and unleashing waves of compassion, creativity, and raw determination, the likes of which I cannot recall seeing in my lifetime. We sense the threat, the feeling of permanence to the darkness already snuffing out light after light. It feels like an emergency.

It is an emergency. I do believe that people are waking up to that simple fact. Many millions of people have come to realize that things have not only gone wrong, but horribly, existentially wrong. The republic is in mortal danger, and the blight will not be contained within our borders. It’s soaking into the Earth’s crust. It’s riding the oceans’ currents. It’s attached to the very molecules we breathe.

There’s no more nudging. We’re heading headlong into a new Dark Age, and a minor course correction will not suffice.

And my fear, my despair, is that it’s too late.

I fear that there aren’t enough good souls in the electorate to transfer power from the monsters in the Republican cult.

I fear that even if we do outnumber the bastards, that they have so twisted our electoral mechanisms that even the bluest of waves could not wash them from power.

I fear that Republicans and their allied extra-national agitators have so successfully sowed confusion and mistrust, not only of our institutions, but of reality itself, that there is no path back to a shared understanding of what is and is not so.

I fear that our better angels are simply no match for our worst demons.

I said this post was a request. I admit, it took me a while to get here. But this is it: Someone convince me I’m wrong.

Show me that the anti-democratic voting laws, the boots on the necks of the poor, the dehumanization of women, the tantrums of white men, the open racism, the soulless quislings, the partisan hacks, the bullies who cast themselves as victims, and the dumptrucks of money sloshing through the system do not spell the end of this American project.

We’re stealing children from their parents and putting them into camps. We’re destroying our ability to inhabit the only planet we have. We’re callously incarcerating generations of black and brown men. We’re revoking the ability of millions to vote. We’re robbing women of the right to control when and whether they give birth. We’re kissing the rings of sociopathic and psychopathic dictators and turning our backs on the world’s democracies. These are just a few things I just now thought of. I could go on.

How does this get fixed? Show me the math and illustrate the physics. Point me to those who are in a position to repair the damage to our democracy, and explain to me how they’ll even find the opportunity to do it. Make me understand how control of a grossly unrepresentative Congress will be wrenched from the iron grip of the evil men who currently wield power.

Persuade me that if the good guys start winning again, that the bad guys will even acknowledge it or allow it. Obviously, nothing is beneath them. The mask of civility has long been discarded, and I don’t believe for a second that they see any means as too savage or too depraved. They have proven this time and again. Ecological catastrophe is fine. Mass poverty is fine. Violence and brutality are fine. Nazis are fine. Sexual assault is fine. What depths are even left to plumb? Let your imagination run wild. They certainly let theirs.

If I’m wrong, if there’s real hope, show me. Make me see how Republicans lose control of Congress, the White House, the Supreme Court, the federal courts, the state capitols, the school boards, and how power gets into the hands of men and women who aren’t moral monsters. Convince me that the haze of misinformation that burns our eyes and ears is not the new normal, and that Americans can have something approaching a shared understanding of reality.

Point me to the light at the end of the tunnel, and prove to me that the tunnel hasn’t already caved in. Because I can’t see it, and it’s getting harder to breathe.

I have withdrawn not only from men, but from affairs, especially from my own affairs; I am working for later generations, writing down some ideas that may be of assistance to them. There are certain wholesome counsels, which may be compared to prescriptions of useful drugs; these I am putting into writing; for I have found them helpful in ministering to my own sores, which, if not wholly cured, have at any rate ceased to spread.

joel l. daniels, a book about things i will tell my daughter

alan jacobs on the commonplace book:

I think I can hazard this claim: Keeping a commonplace book is easy, but using one? Not so much. I started my first one when I was a teenager, and day after day I wedged open books under a foot of my ancient Smith-Corona manual typewriter and banged out the day’s words of wisdom. I had somewhat different ideas then of what counted as wisdom. The mainstays of that era—Arthur C. Clarke and Carl Sagan were perhaps the dominant figures—haven’t made any appearances in my online world. But even then I suspected something that I now know to be true: The task of adding new lines and sentences and paragraphs to one’s collection can become an ever tempting substitute for reading, marking, learning, and inwardly digesting what’s already there. And wisdom that is not frequently revisited is wisdom wasted.

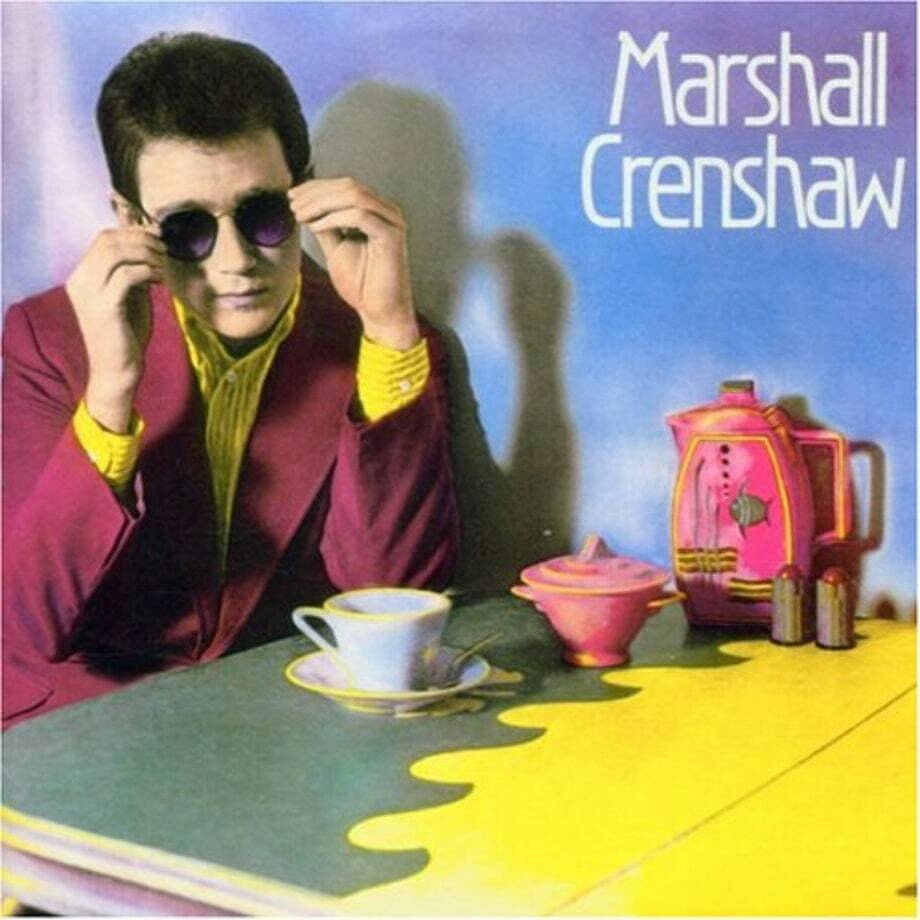

Cynical Boy: Thoughts on Marshall Crenshaw's 1982 Self-Titled Album

Inspired by The Incomparable podcast’s series of “album draft” episodes, I thought it might be an interesting exercise to write about some of the albums that have been the most meaningful to me. So whether or not I decide to do several of these kinds of posts, here’s my first stab at it.

I was very close to never having heard of Marshall Crenshaw. It just so happened that my dad had used a cassette copy of Crenshaw’s eponymous first album to mix down one of his own original songs (Billy Joel’s Nylon Curtain was on the other side, which I’ll probably get into in another post). One day while in my teens, I went searching through my dad’s tape collection to find his song, and gave it a listen. The tape kept playing after dad’s song, and suddenly this simple and engrossing little guitar riff grabbed my attention, and I was pretty much hooked from then on.

I was very close to never having heard of Marshall Crenshaw. It just so happened that my dad had used a cassette copy of Crenshaw’s eponymous first album to mix down one of his own original songs (Billy Joel’s Nylon Curtain was on the other side, which I’ll probably get into in another post). One day while in my teens, I went searching through my dad’s tape collection to find his song, and gave it a listen. The tape kept playing after dad’s song, and suddenly this simple and engrossing little guitar riff grabbed my attention, and I was pretty much hooked from then on.

That riff was, of course, the opening notes of Crenshaw’s “There She Goes Again," which remains one of my absolute favorite songs. It pretends to evince optimism and liberation in the face of separation and loss, but it’s all obviously a mask for the sickening weight of regret and the sting of rejection.

His album, Marshall Crenshaw (1982), largely remains in this vein, with nostalgically styled pop-rock tunes that sound like they could have been recorded in a basement, and I mean that as a compliment. It’s certainly polished, but it also has an immediacy and organic feeling, as though Crenshaw and his band are friends of yours who are working on their record right in front of you.

Once I discovered Crenshaw, I immediately related to him. He’s a smaller guy with glasses who likes hats, and he writes extraordinarily satisfying, hook-infused melodies and arrangements, almost all of which serve as wrappers for some sort of pain, self-doubt, or regret. This element is rarely overt, instead it comes out in comic self-deprecation, little jabs at his blunders, and a kind of hapless, “well what can you do?” persona. I really get that.

Anyway, the album. “Someday, Someway” is the album’s hit, which you’ll still hear once in a while on the radio or pop up in TV shows. It’s a very good song, but it’s not even one of the better ones on the record. Apart from the opening track, highlights include “Rockin’ Around in NYC," which is both bouncy and tense at the same, in which he sings, “I get the feeling that it really was worth coming after we tasted disaster”; and “Mary Anne” with its gorgeous counterpoint backing vocals and its resignation to someone’s else’s despair.

“The Usual Thing” and “Cynical Girl” are rather different in tone, but both are defiant love songs that embrace uniqueness and alienation. On “The Usual Thing,” he worries that giving himself over to someone else will cause him to “lose his energy,” which sounds to me like the lamentation of an introvert. “But,” he tells her, “if I didn’t think you were a little bit out-there too, I just wouldn’t bother with you.”

And on “Cynical Girl,” he longs for a partner who, like him, has “got no use for the real world.” He sings, “I hate TV. There’s gotta be somebody other than me who’s ready to write it off immediately.” Damn right.

I really like a lot of Crenshaw’s other albums, most particularly #447 and Miracle of Science, but Marshall Crenshaw is something truly special, a rare distillation of the delights of classic pop-rock and the pain of being “a little bit out-there.”

Fret No More

Time flies when you’re having fun, and it flies at Mach 5 when you’re not. When I hear my kids complain, “I’m bored,” I tell them how much I envy them. Oh, to be bored! To have no immediate demands on my time, energy, and attention! Boredom may appear to be an unpleasant state, but it’s also a harbinger and a breeding ground of things worth doing. It’s the preamble for activities of choice, not obligation.

By mere coincidence I read in succession two pieces on how terrible we humans are at perceiving time and its passage, and how we might alter those perceptions in a more meaningful and satisfying way. They are both entirely convincing, and yet they each offer conflicting ideal states of mind. Or they might not.

First, Alan Jacobs in The Guardian. (I have never met this man, but I swear I count him among the most valuable teachers of my life.) Jacobs refers to our culture, as driven by our various media, as “presentist.” He writes, “The social media ecosystem is designed to generate constant, instantaneous responses to the provocations of Now.” There’s no way to think deeply or consider alternate or broader perspectives because the fire hose of stimuli never ceases.

The only solution is to cultivate “temporal bandwidth,” which Jacobs defines as “an awareness of our experience as extending into the past and the future.” Less “now” and more “back then, now, and later.” And the way we do that is to read books. Old books, preferably. “To read old books is to get an education in possibility for next to nothing.”

That education sets the stage for one’s mind to not only absorb the wisdom and the mistakes of the past, but to contemplate how they “reverberate into the future”:

You see that some decisions that seemed trivial when they were made proved immensely important, while others which seemed world-transforming quickly sank into insignificance. The “tenuous” self, sensitive only to the needs of This Instant, always believes — often incorrectly — that the present is infinitely consequential.But cultivating temporal bandwidth is happening less and less, it seems. And as Jacobs says in a separate post, “Those who once might have been readers are all shouting at one another on Twitter.”

But while Jacobs recommends steering us away from believing the present to be of prime significance, David Cain at Raptitude urges us to grasp the present more tightly, and let concerns about the past and future fade to periphery.

And it is all to address the same basic problem: we feel washed away by the force and flow of time. Comparing an adult’s perceptions of time to a child’s, Cain writes:

As we become adults, we tend to take on more time commitments. We need to work, maintain a household, and fulfill obligations to others. […] Because these commitments are so important to manage, adult life is characterized by thoughts and worries about time. For us, time always feels limited and scarce, whereas for children, who are busy experiencing life, it’s mostly an abstract thing grownups are always fretting about. There’s nothing we grownups think about more than time — how things are going to go, could go, or did go.Cain doesn’t point to social media or cultural illiteracy as culprits, but rather our disproportionate fixation on the past and the future. It may be that Cain is largely discussing a different scale of time than is Jacobs. Cain seems to be referring to our fixation on what has happened in the relatively recent past (10 minutes ago or 10 years ago, for example) and what the immediate future bodes (say, the next couple of hours or the next couple of months). Jacobs, by emphasizing the reading of “old books” (and by quoting lines from Horace) is certainly thinking of a much deeper past and a more distant future, spans that transcend our own lifetimes.

But as I said, Cain recommends regarding the past and future less, and home in on the present. “The more life is weighted towards attending to present moment experience, the more abundant time seems,” he says. And the way to attend to that present moment, as clichéd as it might sound these days, is through mindfulness, which can mean meditation or any activities “that you can’t do absent-mindedly: arts and crafts, sports, gardening, dancing.” Here’s why:

It’s only when we’re fretting about the future or reminiscing over the past that life seems too short, too fast, too out of control. When your attention is invested in present-moment experience, there is always exactly enough time. Every experience fits perfectly into its moment.Note that Cain never mentions reading as one of those activities that one can’t do absent-mindedly. I don’t know about you, but if I read absent-mindedly I’m probably not actually reading at all, or at least not in such a way that I’ll retain anything. So whether or not he intended it or agrees with it, I’m throwing “reading books” into that list.

This is the bridge that connects these seemingly-conflicting viewpoints, making them complementary. Much of this rests on the difference in time scale I referred to, which, if taken into account, begins to form a complete picture. Few would argue with the idea that fretting about the immediate past and future is detrimental to one’s experience of time, or that contemplation and consideration of history and the long-term repercussions of our actions is a waste of time.

They key word here might indeed be “fretting.” In this sense, the definition of “fretting” isn’t limited to “worrying,” but describes a broader practice of wasting energy and attention on things within a narrow temporal scope without taking any meaningful action to address whatever concerns might be contained within. We fret about choices we’ve made and what such-and-such a person is thinking about us or how we’ll ever manage to get through the day, week, or year with our sanity intact. We rarely fret about how the Khwarazmian Empire was woefully unprepared for the Mongol army under Genghis Khan in 1219, or how the human inhabitants of TRAPPIST-1d will successfully harvest the planet’s resources to support a growing populace.

And of course, nothing engenders fretting like social media. Already primed for fretting by the demands of work, family, and self-doubt, now we can fret in real time (and repeatedly) over anything relatives, acquaintances, total strangers, politicians, celebrities, and algorithms flash before our awareness. It is possible to exist in a state of permanent fret.

Let me tell you, time really freaking zooms when you’re fretting.

So let’s combine the recommendations of Jacobs and Cain to address our temporal-perception crisis. Let’s get off of Facebook and Twitter, let’s turn off the television, and let’s get to that stack of books (or list of ebooks if you prefer) and read. Let’s allow our brains to expand our awareness, considerations, and moral circle beyond this moment, this year, this era. Let’s not burden ourselves with the exhausting worries about what we’re reading or how long it will take to read it or what else we should be reading but aren’t. Let’s make time to chat with our kids and our parents, and write, tinker, draw, arrange, organize, build, repair, or tend as best suits us. Let’s stop and breathe and think of nothing for a few minutes as we focus on the present instant in time and space, even to the atomic level. And then let’s think big, daring, universe-spanning thoughts beyond all measure.

Let’s be bored, and let that boredom nudge, inspire, or shock us into activity, be it infinitesimal or polycosmic.

It will take practice. It will not be easy. Let’s accept that this, too, is a journey of time and effort and moments.

And let us fret no more.

If you feel so inclined, you can support my work through Patreon.

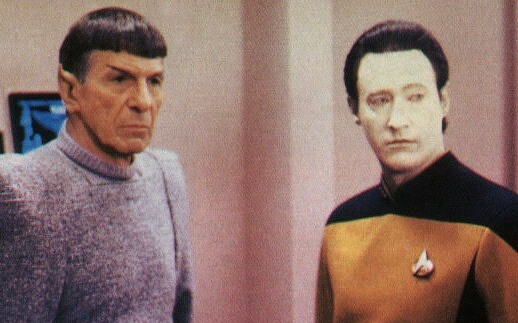

Spocks and Datas

SPOCK: He intrigues me, this Picard.DATA: In what manner, sir?

SPOCK: Remarkably analytical and dispassionate, for a human. I understand why my father chose to mind-meld with him. There’s almost a Vulcan quality to the man.

DATA: Interesting. I have not considered that. And Captain Picard has been a role model in my quest to be more human.

SPOCK: More human?

DATA: Yes, Ambassador.

SPOCK: Fascinating. You have an efficient intellect, superior physical skills and no emotional impediments. There are Vulcans who aspire all their lives to achieve what you’ve been given by design.

DATA: You are half human.

SPOCK: Yes.

DATA: Yet you have chosen a Vulcan way of life.

SPOCK: I have.

DATA: In effect, you have abandoned what I have sought all my life.

- Star Trek: The Next Generation, “Unification Part 2” (1991)

For the socially alienated, such as autistics like myself, the characters of Spock and Data from Star Trek are immediately relatable. Not because of their lack of emotion, but because of their estrangement from their peers. Extraordinarily intelligent, yet unable to understand the motivations or the social and emotional needs of the humans around them. Though full members of their respective crews and fully equal members (eventually, for Data) of their adopted societies, they are nonetheless alone.But apart from being non-human, the sources of Spock’s and Data’s alienation are quite different. Spock, genetically half-human and half-Vulcan, aspires to overcome the psychological weaknesses he believes his human side burdens him with. Data, the creation of humans, has put himself on a quest to exhibit the qualities of humanity as faithfully as possible. While he may be confused by human weaknesses, he nonetheless wishes to replicate them.

Framed this way, Data may be the more relatable to the socially alienated. Those with Asperger’s like me, for example, are obviously the product of humans, and live and work among other humans, but struggle to make meaningful social and emotional connections with the neurotypical majority. This is painful, and there seems to be no remedy. No matter how hard they try to ape the behavior of neurotypicals, it is just that, an aping. And yet they, we, pine for that connection. For belonging.

Spock represents something that I would guess is less common, the socially alienated person who wishes to remain alienated, because to assimilate would be to corrupt oneself, to debase oneself. Surely there are those intellectuals and savants who identify with Spock in this, and surely they too experience the discomfort of alienation. But I suspect that is the Datas among us that are truly suffering from their estrangement.

Spock represents something that I would guess is less common, the socially alienated person who wishes to remain alienated, because to assimilate would be to corrupt oneself, to debase oneself. Surely there are those intellectuals and savants who identify with Spock in this, and surely they too experience the discomfort of alienation. But I suspect that is the Datas among us that are truly suffering from their estrangement.

To the normals and the neurotypicals, I have to assume that these two dispositions, the Spock and the Data, are more or less indistinguishable. Both exhibit as emotionally distant. Both are prone to say things that, to the normals, are considered inappropriate, offensive, or bizarre, despite innocent or benign intentions. Both invite varying degrees of pity or condescension from normals for what they perceive as naivete or “disability.”

For a Data, there is a constant pull toward the group, a tug toward the tribe. The Data will practice the mannerisms and idioms of the normals, and often fail laughably. For a Spock, the social distance is actively maintained. Rather than gravitate toward inclusion, they prefer to observe from a safe and less distracting distance. There is no attempt to do as the Romans do. To the Spock, the Romans are silly.

From my own point of view, to adopt the Spock approach would be a luxury. While I do not believe that a Spock-type never suffers in her alienation, she certainly suffers less. A Spock has already decided that there is little to be gained from full social inclusion, and little to envy from the normals’ mindset. What a relief that would be.

The Data, however, is all too aware of the myriad ways she does not match up to her normal peers. She suffers from the humiliation of failed attempts to assimilate, and she suffers from her solitude. And unlike the character of Data the android, Data-types definitely experience emotions, often severely. It is a sisyphean way to live, except that everyone is watching and audibly commenting on how weirdly one is pushing the rock up the hill.

The Data, however, is all too aware of the myriad ways she does not match up to her normal peers. She suffers from the humiliation of failed attempts to assimilate, and she suffers from her solitude. And unlike the character of Data the android, Data-types definitely experience emotions, often severely. It is a sisyphean way to live, except that everyone is watching and audibly commenting on how weirdly one is pushing the rock up the hill.

In a previous piece, I chose another Star Trek character as an Aspie-analogue, and reflecting on it now, it seems to fill a kind of middle-ground between the Spock and the Data. I’m talking about Odo. I wrote:

If Spock and Data show us two poles of how the socially alienated cope with their weirdness, Odo shows us the consequences of all that work. What does the outcast do after all the failed attempts to commune, or after a day of navigating the incomprehensible absurdities of the normals’ behavior? What toll does it take?Though he takes a humanoid form as best he can, no one thinks Odo, the changeling, really looks like them. He doesn’t understand humanoid behavior, but he does try to map it out in order to follow others’ motivations and how they lead to actions. He is impatient with the things that humanoids seem to find fulfilling and important, which to him seem pointless and wasteful. He comes off as mean when he doesn’t intend to. He craves companionship, but knows he can’t have it. And when it all comes down to it, when he’s tired of pretending to be one of the “solids,” he must — absolutely must — return to his bucket. He must resume his true liquid form, stop pretending, find total solitude, and rest.

Odo shows us. We must return to our bucket, or we dissolve.

Please consider supporting my work through Patreon.

Busted Heart

How’s this for an eventful couple of years: I discovered that I was autistic. I lost much of the hearing in my right ear for reasons unknown. I turned 40.

And now—let’s go ahead and rip this excruciating band-aid off—my marriage of ten years has ended.

(This is not going to be a post about what lead to this, nor will it be about the ongoing cascade of pain, depression, and fear I’ve experienced, as I’m just not ready for that, so adjust your expectations accordingly.)

The cliche about turning 40 is that I am now “over the hill,” and if so, the timing for that could not be worse. Over the course of two years I have made the most profound self-discoveries of my life, having the nature of my brain, personality, quirks, aversions, talents, and handicaps revealed to me as products of Asperger’s syndrome. In the midst of this, I was given opportunities to put my talents into practice in new ways; directing plays, doing a residency at a writers’ refuge, hosting a podcast with an actual audience, writing for an excellent technology website, and soon, the publication of my work in a journal near and dear to my heart. Of course I’ve also been learning to deal with my hearing loss.

The end of my marriage, obviously, is quite something else. It is utterly disorienting. It gives me the feeling of being uncontrollably adrift, like an astronaut on a space walk whose tether has been severed. This is particularly so considering that Maine is not my home turf. We came to live here to be near my wife’s family. While they have gone out of their way to make certain that I feel that I am still and will always be a part of that family, it remains that I have no circle of friends here of my own. Almost all of my acquaintances are second-degree connections from the marriage. Because of the love of these wonderful in-laws (former in-laws?), I am not actually alone. But because I have no social or familial foundation of my own, in some important ways, I am indeed alone.

I keep thinking of the song “Busted Heart” by the band Bishop Allen, which says:

Follow me To the shipwreck shores Of a dark and strange country I was born A stranger thinking out loud In a foreign tongueThis reminds me of how I feel in any new environment, really, but seems particularly apt for suddenly finding myself spouse-less in Maine.I was out of place I was looking all around Just a trying to find a friendly face But they’re all gone

What a thought. At the dawn of my fifth decade, I am forced to reset. I begin 40 without nearby close friends, without nearby relations, and without a significant other. (In fact, I haven’t been “single” for more than 16 years.) I begin 40 with a new debilitation, my hearing loss, and with a still-new and bewildering understanding of why I am as weird as I am, my autism.

In one positive sense, it’s a refreshing chance to “start over,” and begin a fresh, new life with a deeper understanding of who I am, what I’m capable of, and what I’m not. But it’s not really starting over, because the time has still passed. I don’t get to start from 18 again. I still have to go from 40.

And so it must be. When I was diagnosed as autistic, part of me mourned for the years I had lost in which I had no idea why I was the way I was, why I couldn’t meet others’ expectations of normalcy, why I couldn’t bring myself to share others’ priorities or interests, and why I felt like a member of some different species.

The second verse of “Busted Heart” reminds me of what it’s like to be weird like me, to have Asperger’s:

And wisdom is a whisper And I’m trying to understand What I say, what I think, Where I sleep, when I breathe What I do with my handsSo perhaps I am now in a dark and strange country, but maybe it means I have the chance to re-enter that country with this greater understanding, but instead of laboring to apologize and make up for my oddness, I can embrace it, and advocate for my right to be the way I am. More than that, maybe I can “be like what I’m like,” and consider my differences to be positive, distinguishing qualities.

Maybe.

No, really. Maybe. The song is called “Busted Heart,” which is a sad thought. But read the lyrics of the chorus:

And a busted heart Is a welcome friend And when that heart leaves What will you do then?Really, my heart was busted long before my marriage, long before I grew up. In a way, I was born with a busted heart. But you know what? A busted heart is a welcome friend. Not to me, but to others. I’m a little broken, and I think out loud in a foreign tongue, but because of that, not in spite of it, I might be worth having around...to someone.

I’m 40. I’m over the hill. Over that hill is a dark and strange country. But maybe the people there will be cool.

Maybe.

[youtube www.youtube.com/watch

Hearing, Loss

It’s the late autumn of 2017, and I’m in Point Reyes Station, California for a two-week writers’ retreat. I was walking down a remote road, taking one of my regular strolls into town for supplies, a bit of exercise, and to take in the landscape, which was stunningly beautiful. The weather was nearly perfect, and being so removed from everything, cars and other pedestrians on the road were quite rare. I was alone and enjoying the movement and the environment.

The wind picked up a little and it whooshed deeply in my ears. You know the sound, the low thup-thup as the air pummels your earlobes. Maybe I hear it more than others because my ears are little on the bigger side, so they scoop up a bit more air.

Only something was off. The whooshing sound was there, but it was only coming in on the right side of my head. That was weird. I must have just happened to be facing in such a direction that the wind was hitting my head at that particular angle. So I checked.

I pivoted my head in different directions, while walking, while standing still, and nothing changed. I walked to different parts of the road with different landscape features; fewer trees, fewer houses, atop an incline, then toward the bottom. Still the same. I wasn’t hearing the wind in my right ear at all.

I snapped my fingers in both ears, and noticed no meaningful difference. I rubbed my finger along the surface of my earlobes and ear canals. In the left ear, I could hear the deep rubbing and rumbling sounds of the friction. In my right ear, I heard a faint and wispier sound, like something soft brushing on paper, at a distance.

I got out my headphones and attached them to my phone. I played some songs, and only listened through one earbud at a time. In the left ear, the full, rich sound came through that I had come to expect and enjoy from this particular pair of headphones. In my right, the bass and mids were, alarmingly, almost nonexistent, save for the high-frequency sounds of strings being scratched or plucked. All I heard were higher-end sounds, such as vocals, snares, and cymbals, only much tinnier, thinner, weaker.

Finally, I tried listening to a voicemail to see if I could hear a phone call. Again, the expected normal sound of the voice came through the phone’s little speaker into my left ear. Putting the phone up to my right ear, the voice sounded like it was coming from a tin can stuffed with cotton. I could hear the voice, but barely.

This was unmistakable. I wasn’t being paranoid. I had lost hearing in my right ear.

*

It’s the spring of 1994 in Absecon, New Jersey. I’m a 16-year-old junior in high school, in an exurban basement. It’s the house of one of my friends from marching band, Chris, and by way of some now-forgotten confluence of agreements and compromises, I have formed a crappy little band with him and two other friends; Chris on drums (talented thrash metal devotee), my best friend Rob on bass (had never played, and was borrowing my dad’s sort-of vintage bass guitar), me on lead guitar (I had no business being a lead guitarist but I could play chords and learn songs by ear relatively easily), and one guy I met through Chris, Corey, our lead vocalist, a kind of Axl Rose/grunge type (and who was tone deaf).I told you it was a crappy band.

Nonetheless, it was my band, and my sole outlet for playing with a full set of musicians on a few songs I really liked (and some I really didn’t, but like I said, agreements and compromises). In the year or so we played together, I don’t know that we ever got to the point of being “good,” but we did manage to scrape together a handful of songs that we could enjoyably hack our way through. It was fun, at least some of the time.

On this occasion, we’ve been a band for a few months, and Corey and Chris have brought with them a friend of theirs, another guitarist who was straight from the Metallica/Megadeth school of metal. He had the requisite long hair and patchy teenage facial hair, including that mustache so many of those guys wore back then that usually signaled to me, for some reason, that I should be wary of them. I don’t remember his name, so let’s just call him “Patchy-stache.”

Apart from having some obviously advanced skills in metal lead guitar, Patchy-stache also brought with him something else we didn’t have: a giant-ass stack of huge amplifiers. For our usual rehearsals, I hauled back and forth my dad’s ancient Vox tube amp and a very small beginner’s amp that I’d gotten as a birthday present. Corey had a decent amp and PA for his vocals and occasional guitar playing. With what we had, we could barely hear ourselves over the astounding pound of Chris’s drums. That guy did not mess around behind that set. Usually I wore earplugs to protect my hearing, though not always. I was afraid it made me seem like a wuss.