essays

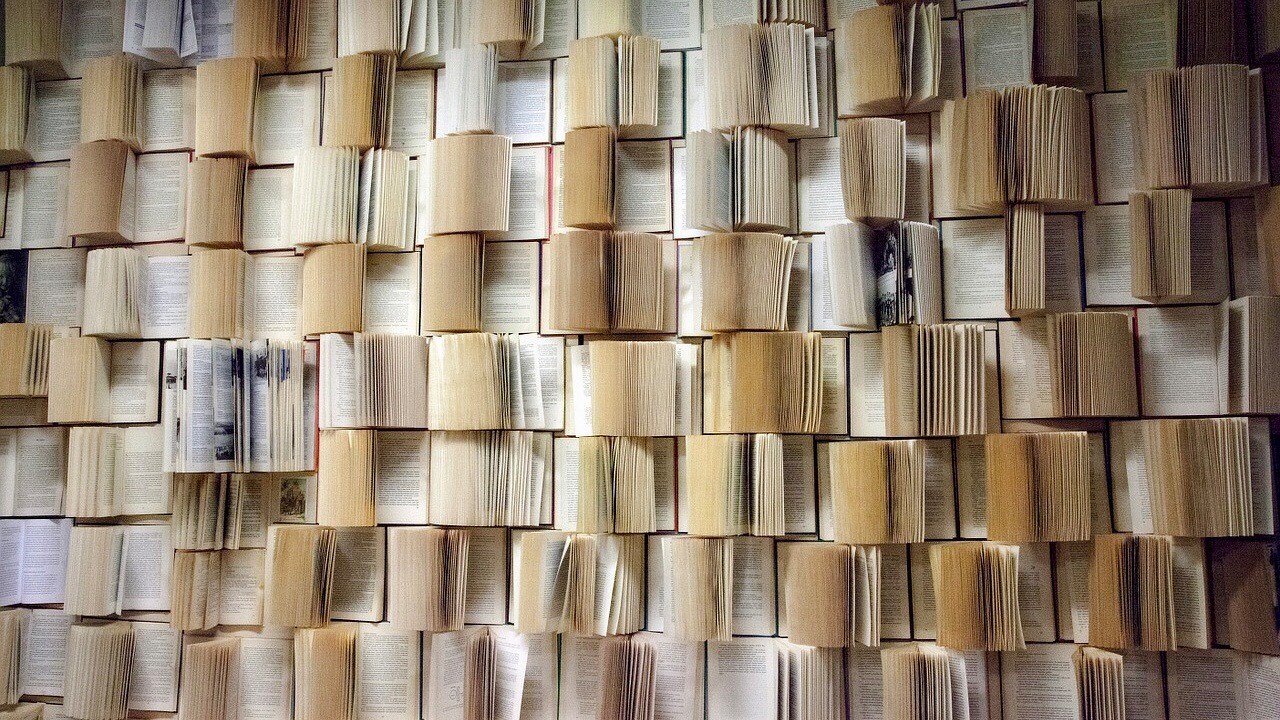

Surround Yourself with Books, Save Humanity

Although I certainly have little patience for the fetishization of books as decorative status symbols, I have a deep affection for the physical, dead-tree book as a medium. Unlike an electronic device, to see and hold a single volume is for me to feel the thoughts and ideas it contains seething within its closed pages, like there is a flow of energy that is eager for a conduit through which it can propagate. I love that. And I feel it both before and after having read a meaningful book.

Although I certainly have little patience for the fetishization of books as decorative status symbols, I have a deep affection for the physical, dead-tree book as a medium. Unlike an electronic device, to see and hold a single volume is for me to feel the thoughts and ideas it contains seething within its closed pages, like there is a flow of energy that is eager for a conduit through which it can propagate. I love that. And I feel it both before and after having read a meaningful book.

As a consumer of books, however, I also find ebooks almost miraculous in their convenience and utility. In a single device I can have literally thousands of books at the ready, which expands to millions if my device is connected to the Internet. I can infinitely annotate these books, entirely nondestructively. The device even provides its own damn reading light. Books feel great, I adore them, but to dismiss the ebook and particularly ebook readers like the Kindle is absurd.

But in one crucial way, ebooks’ greatest strength also is their greatest weakness. And I mean weakness, not flaw, as I’ll explain.

I’m thinking about this because of Timothy Snyder’s On Tyranny, a book that is all at once easy, enriching, and gut-wrenching to read. Among Snyder’s 20 lessons for avoiding life under some kind of Trumpian Reich are his recommendations that we a) support print journalism and b) read more books. Now, it’s fairly obvious why good journalism needs to be bolstered in times such as these, for it may very well be the last layer of defense we have from a media entirely made up of propaganda. He writes:

The better print journalists allow us to consider the meaning, for ourselves and our country, of what might otherwise seem to be isolated bits of information. But while anyone can repost an article, researching and writing is hard work that requires time and money.That’s very clear. But by print journalism, does he merely mean deeply researched, sourced, and fact-checked reporting regardless of medium, or does he also mean that this quality journalism must be, by necessity, literally printed on paper? I’ll return to that in a bit.

Back to books. Right now, my 7-year-old son is enamored with a series of kids’ nature books in which one animal is pitted against another in a “who would win” scenario (like crab vs. lobster or wolverine vs. Tasmanian devil, for example). He’s collected eight or so of these slim little books, and he loves them so much, he’s taken to carrying them – all of them – around with him wherever he can.

“Daddy, I don’t know what it is,” he says, “but these books have just made me, well, love books!”

I’m delighted that he’s so attached to these books, that he has this affection for them. I know that wouldn’t be possible if he only had access to their contents on a tablet. The value of the content is no different, but he can show his enthusiasm in a real, physical way that a digital version wouldn’t allow. The objects, being self-contained with the words and pictures he loves, take on more meaning. And by assigning so much meaning to the objects, he imbues the content itself more meaning too.

What does a kids’ book with a tarantula fighting a scorpion have to do with resistance to tyranny? Let’s see what Snyder has to say about the contrast between books and digital/social media:

The effort [of propagandists] to define the shape and significance of events requires words and concepts that elude us when we are entranced by visual stimuli. Watching televised news is sometimes little more than looking at someone who is also looking at a picture. We take this collective trance to be normal. We have slowly fallen into it.Snyder cites examples from dystopian literature in which the fascist state bans books and, as in 1984, the consumption of pre-approved electronic media is monitored in real time, and in which the public is constantly fed the state’s distortion and reduction of language, all “to starve the public of the concepts needed to think about the present, remember the past, and consider the future.“

What we need to do, what we owe it to ourselves to do, is to actively seek information and perspectives from well outside official channels, to fortify our consciousness from being co-opted and anesthetized, and to expand our understanding of the world beyond the daily feed. Snyder says:

When we repeat the same words and phrases that appear in the daily media, we accept the absence of a larger framework. To have such a framework requires more concepts, and having more concepts requires reading. So get the screens out of your room and surround yourself with books.But what if the screen is displaying the same concepts as those books? “Staring at a screen” when one is reading an ebook is a very different practice than staring at it for Facebook-feed-induced dopamine squirts. Even more so if the screen with the ebook is on a dedicated e-reader like a Kindle, which intentionally withholds many of the distractions immediately available on a phone or tablet. Heck, I read Snyder’s book on my Kindle.

You won’t see me arguing that ebooks are inferior to physical books when we’re talking about the usual day-to-day reading of books, hell no. But in the context of this discussion, think about how we get ebooks onto our devices. They exist digitally, of course, and in the vast majority of cases they come from a given corporation’s servers with the ebook files themselves armed with some kind of digital rights management in order to prevent anyone from accessing those files on a competitor’s device. (Not all ebook sales are done this way, but they are very much the exception.) When we buy an ebook, in most cases, we’re not really “buying” it, we’re licensing it to display on a selection of devices approved by the vendor. And so it is with most music and video purchases.

Those ebooks are then transmitted over wires and/or wireless frequencies that are owned by another corporation, access to which we are once again leasing. So even if you are getting DRM-free, public domain ebooks in an open format like ePub that is readable on a wide variety of devices, you probably can’t acquire it unless you use a means of digital transfer that someone else controls.

You see what I’m getting at. Ebooks come with several points of failure, points at which one’s access to them can be cut off for any number of reasons. Remember a few years back when, because of a copyright dispute over the ebook version of 1984 (of all things), Amazon zapped purchased copies of the book from many of its customers’ Kindles. It didn’t just halt new sales, or even just cut off access to the files it had stored on its cloud servers. It went into its customers’ physical devices and deleted the ebooks – again, ebooks they had paid for. Customers had no say in the matter.

This was more or less a benign screwup on Amazon’s part. Presumably it had no authoritarian motives, but it makes plain how astoundingly easy it is for a company to determine the fate of the digital media we pretend we own.

This is about permanence. A physical book, once produced, cannot be remotely zapped out of existence. While some fascist regime could indeed close all the libraries, shut down all the book stores, and even go house to house rounding up books and setting them ablaze, physical books remain corporeal objects that can be held, passed along, hidden, smuggled, and even copied with pen and paper by candlelight. If the bad guys can’t get their actual hands on it, they can’t destroy it. And it can still be read.

But for ebooks, all it would take would be a little bit of acquiescence from the vendor (or the network service provider, or the device manufacturer) and your choice to read what you want could be revoked in an instant. Obviously, the same goes for video, music and other audio, and of course, journalism. The ones and zeroes that our screens and speakers convert to media can be erased, altered, or replaced and we wouldn’t even know it was happening until it was too late.

Physical books, along with print journalism (literal print), come with real limitations and inconveniences that electronic media obviate. But those same limitations also make them more immutable. It fortifies them and the ideas contained within them. Though constrained by their physical properties, they also offer the surest path to an expanded, enriched, and unrestricted consciousness. One that, say, an authoritarian state can’t touch.

Here’s an example of what I mean, once again from Snyder, with my emphasis added:

A brilliant mind like Victor Klemperer, much admired today, is remembered only because he stubbornly kept a hidden diary under Nazi rule. For him it was sustenance: “My diary was my balancing pole, without which I would have fallen down a thousand times.” Václav Havel, the most important thinker among the communist dissidents of the 1970s, dedicated his most important essay, “The Power of the Powerless,” to a philosopher who died shortly after interrogation by the Czechoslovak communist secret police. In communist Czechoslovakia, this pamphlet had to be circulated illegally, in a few copies, as what east Europeans at the time, following the Russian dissidents, called “samizdat.”If those had been the equivalent of online articles, they’d have been deleted before they ever reached anyone else’s screens.

There’s one additional step to this, one more layer of intellectual “fortification.” It’s about the act of reading as something more than a diversion, more than pleasure. Because if we only read the digital content that’s been algorithmically determined to hold our attention, or even if it’s one of our treasured print books that we read for sheer amusement, we’re still missing something.

Today I happened to see Maria Popova of Brain Pickings share a snippet from a letter written by Franz Kafka to a friend, in which he explains what he thinks reading books is for (emphasis mine):

I think we ought to read only the kind of books that wound and stab us. If the book we’re reading doesn’t wake us up with a blow on the head, what are we reading it for? So that it will make us happy, as you write? Good Lord, we would be happy precisely if we had no books, and the kind of books that make us happy are the kind we could write ourselves if we had to. But we need the books that affect us like a disaster, that grieve us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves, like being banished into forests far from everyone, like a suicide. A book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us. That is my belief.We don’t need books to achieve mere happiness. To expand our intellectual and moral horizons; to give our minds the armor they need to withstand the assaults of misinformation and stupification; to be made wiser, more empathetic, and more creative than we are, we need to read those books that affect us, “like a disaster” or otherwise.

To fully ensure that we have those books, that they can be seen and held and smelled and shared and recited and experienced outside the authority of a state or corporation, they need to be present, corporeal objects. They need to exist in the real world.

So, please, do use that Kindle for all it’s worth; use it to read all the books that wake you up, blow your mind, and change your life.

But also, if you can, surround yourself with books. In a very real way, they might just save us all.

iPad Pro 10.5": Wonderfully Unnecessary

I had lost interest in tablets for a while. I hate owning redundant possessions, and as large-screen phones became my norm, owning a tablet as well felt decadent. No one needs a tablet.

Eventually I remembered that “need” isn’t the point. As I discussed in my iPad Air review many years ago, the tablet is the device you choose to use when you are no longer compelled by necessity to use a phone or a PC. It’s for the things you want to do as opposed to the things you have to do. Your phone and PC can do things you want as well, but the tablet would ideally be specifically suited to activities of non-compulsion. I’m talking about things like reading (books, articles, comics, etc.), browsing, watching videos, playing certain kinds of games, as well as, for many, drawing, designing, making music, and for me in particular, creative writing.

Not writing for work. I’ve become something of a stickler for intentionally separating my work machine from my leisure machine, even though I work from a home office using my own laptop. Most of the time, the laptop is for work-work, and the tablet is for the writing and creative work that I do by my own whim.

To sum up, here is my Theory of Devices:

- Generally speaking, though with countless exceptions, phones and PCs (laptops or desktops) are “lean-in” devices of necessity. One squints and scrunches one’s attention (and fingers) on the small screen of the phone in order to accomplish the tasks demanded by the moment. One hunches over the keyboard and display of a laptop, studying the contents of the screen and dutifully typing away to, again, satisfy the demands of the moment. They require a kind of tunnel vision.

- Tablets (and e-readers like Kindles) are “lean-back” devices of choice. Generally hand-held, but large enough to encourage the user to kick back and absorb content rather than actively scrutinize it. If one wishes to more deeply engage and create or “work,” that’s fine. There is a psychological separation between the work machines and the diversion machine.

Late last year I got the iPad Pro 9.7”. It was more than I absolutely needed, as an iPad Air 2 would have more than sufficed for almost all my tablet needs, but I was too intrigued by the possibilities presented by the Apple Pencil to settle. Having used a couple of Galaxy Notes, I knew very well the vast difference between just using any old stylus on a touchscreen, and having a stylus specifically built for your particular machine, a machine with software and hardware tuned to interact with that stylus. (This is part of why a strongly considered a Surface Pro 4, but decided it was both too expensive and too close to being a work machine.) So iPad Pro it would have to be.

I loved it. I loved it more as the months went by. I kept finding myself impressed by its speed, fluidity, responsiveness, and the sheer loveliness of its display. I made lots of fun pictures with 53’s Paper app, and even made delightful musical arrangements with iOS GarageBand (which has become really quite an astounding application in recent years). I did a little writing on it as well, but not nearly as much as I’d like, partly I think because I failed to find a keyboard solution I was truly comfortable with. More on that later.

But I always wanted a slightly bigger screen than iPads offered. Having seen Surface Pros, the Pixel C, and the pre–2015 Samsung Tab S’s, I knew that a larger canvas would really open the device up for me. The 12.9” iPad Pro was always utterly intriguing, but I knew that it would be too unwieldy to be the lean-back device I needed it to be.

Then Apple announced the new 10.5” iPad Pro, and I was ready to pounce. Not because of any flaws in the 9.7” Pro, but because a slightly-larger super-iPad was What I’d Always Wanted. I would later describe it as the first-worldiest of purchases. But shit, life is short, and this is all I spend money on. And now a very nice Swappa user in New York City now has my 9.7” Pro, and I have his money. Or, I did. I gave that money to Apple. Again.

I’ve had the iPad Pro 10.5” for about a week. I haven’t pushed it to its limits (nor do I know how I would go about that), but I’ve used it for all of the things I would normally use a tablet for, and as you’ll see, I don’t need much else to go on.

*

So how is it?It’s a really good iPad. You already know what an iPad is and does, so, yes, the 10.5” iPad Pro is the best at all those things, with a little bit more room on the screen on which to enjoy those things. It’s the same weight as iPads have been since the iPad Air in 2013, about a pound, and it’s super thin.

The expanded screen size is very nice, and there are times I pick the thing up and turn it on and I’m taken aback by that little increase in visual immersion. But in regular use, it’s not world-changing. It’s a little bit nicer, and it makes the software keyboard easier to use accurately.

If anything, it reminds me of the Google Pixel C, which was my “pro” tablet of choice before the iPad, but I gave up on after it suffered from technical failures (such as a screen that quickly went on the fritz) and abysmally poor customer support for said failures. But one of the great things about the Pixel C was its screen size at 10.2", so having an iPad with about the same screen size is a way for me to get back some of what I really loved about Google’s tablet.

The iPad Pro, regardless of the change in screen real estate, has kept the same pixel density at 264 ppi. I’m frankly disappointed that Apple hasn’t bumped this up even a little bit since the introduction of the iPad 3 in 2012. I’ve been using quad-HD phones, and the Pixel C had a gorgeous 308 ppi display. Hell, even the iPad mini line has 326 ppi.

It really doesn’t matter, though. I almost never notice the lower pixel density of the iPad Pro, and Apple’s done so much to make this screen crisp and beautiful in so many other ways that no one else even attempts, let alone achieves. TrueTone, though unnecessary, is a nice adaptive-color technology that is better to have than not. The display itself is just about painted onto the glass, so there’s no sense of gawking at your content as though it’s beneath a window pane. I would certainly like the ppi to be higher, and I know I’d notice it and appreciate it, but I have no complaints about the iPad Pro’s display.

I can talk about performance, but honestly, the real test of that will come with iOS 11 this fall, when the operating system transforms from giant-phone-OS to something that genuinely seems ready to be used as a full-power computing device. Other than that, everything is as fast as you’d imagine it to be. But of course the same was true for the 9.7” Pro, so I doubt anyone would perceive any difference between the two.

The bigger change is this boost from a 60hz refresh rate to 120hz. This does indeed make scrolling and animations more fluid. At times it looks so good it’s otherworldly, but you also just get used to it and it’s no big deal. Again, better to have than not, for sure. Some are describing this change as almost akin to the difference between Retina and non-Retina, and I don’t agree…yet. I do really appreciate it, but I suspect that once again its utility will become more apparent with iOS 11.

The refresh rate boost is also supposed to improve the display’s interaction with the Apple Pencil, reducing latency to almost imperceptible levels. I can feel the difference in apps like Apple’s Notes and 53’s Paper, but not in other drawing apps. This might be because they haven’t taken advantage of the new hardware yet and likely will, but right now there’s no difference I can sense in many Pencil-related apps. This is another area where there were no problems with the performance on the 9.7” Pro, and the Pencil on the 10.5” does it a little better.

*

I’m trying to decide whether Apple’s own Smart Keyboard is good and useful enough to justify holding onto. I purchased it alongside the iPad, assuming it would be almost necessary to get the full “Pro” experience. But, like the iPad, it was not cheap.It is much nicer to type on than its predecessor for the 9.7" Pro, with keys more widely spaced, but also like 9.7’s it also makes for a clumsy iPad cover. It’s heavy for a cover, and its weight is (necessarily) uneven. While it’s wonderfully easy to take on and off, it’s too expensive to casually toss aside like you might do with a plain cover (which are also grossly overpriced). It is somewhat deceptive in that it doesn’t look like an expensive piece of electronics, but it is, and one does not want to have it snap in half because you didn’t know it was sticking out of the couch cushions before you sat or laying on the floor as you smash it with your feet.

As before, it pairs with the iPad immediately upon magnetic contact, so there’s no fiddling. One little annoyance I’ve discovered is that if before you attached the Smart Keyboard you had been using a third-party software keyboard, the Smart Keyboard gets a little confused. I like to use Gboard as my software keyboard, but if it’s the most recent one I’ve enabled when I attach the Smart Keyboard, at least one key (the apostrophe) doesn’t work. Maybe others fail too, but that’s the one I noticed. Cycling back to enabling the default keyboard solves the problem.

Oh, and once again, it doesn’t have a place to stow the Apple Pencil. Argle blargle.

For a couple of years now I’ve had the Microsoft Universal Mobile Keyboard, and it is very good for what it is, and tablets and phones alike sit nicely in it’s little device slot. I don’t think it’s quite as nice to type on as the Smart Keyboard, and, obviously, it doesn’t have the advantage of being physically attached to the iPad. You have to go get it to use it. The Apple Smart Keyboard is always there, either on the iPad itself or within arm’s reach.

I don’t really trust any of the other keyboard cases I’ve seen because in each of them the keys have at least the potential to rub up against, and thereby scratch, the screen. That’s not gonna fly. With the Smart Keyboard, the keys fold away and make no contact with the display, ever.

I believe I may be convincing myself to keep it. As much as I’d like to recoup that cash. I should experiment with the Microsoft keyboard again, just to be sure, so as I write this, I’m just not certain about the Smart Keyboard.

And quite frankly, I often prefer typing on the software keyboard. I wouldn’t even consider an external keyboard if the software keyboard didn’t take over so much of the screen. But I’m using it now to type this, and I suppose this is another benefit of the 10.5” screen: a more comfortable on-screen keyboard and more remaining space for the content.

*

Some smaller things worth noting:- I am overly sensitive to devices that get too warm. It was perhaps my greatest source of dissatisfaction about iPads 3 and 4, and was a rollercoaster struggle with the Nexus 6, among other devices. I have yet to feel this tablet get meaningfully warm. The 9.7” Pro never bothered me either, though I could notice changes in temperature. So far, I can only attribute any warmth to the 10.5” Pro to the heat from my own hands.

- The speakers are excellent for a super-thin wafer of a computer. Better than any other device I’ve used that isn’t itself a dedicated speaker or sound system.

- I used to much prefer using any tablet in portrait mode, seeing it as the “correct” orientation, particularly for lean-back uses, but something about the increase in screen size makes landscape nice for more passive use as well, in that you can easily split the screen between two apps and still feel like you’re looking at two iPad mini-size devices.

- The camera is apparently amazing, but I’ve used it almost not at all. I have no idea if this will change, but I am definitely not one of those “omg never use a tablet to take pictures” people. Seriously, use whatever gadget you have the way you want to. Your tablet has a camera and a giant-ass viewfinder. Go ahead and take pictures. (Just don’t be obnoxious about blocking people’s view with it.) It’s supposed to be an iPhone 7-quality camera, which sounds great. Hard for me to see when I’d take advantage of this, but hey, it’s there.

- There is a problem with Google Photos that hasn’t been addressed yet, where the application grinds to a halt when trying to edit any photo. This did not happen with the 9.7” Pro, and a couple folks online have had the same experience. I have no idea why this would be, but I hope a software update comes quickly.

*

Clearly, the 10.5” iPad Pro is a fantastic tablet. Almost certainly it’s the best tablet available, and by several orders of magnitude. It’s more tablet, and really, more computer, than almost any one in the market could possibly need. And that’s good, because if there’s one thing even Apple was surprised to learn, it’s that people buy iPads and then hold on to them and use them for many years. This iPad will fare very well over those years, I predict.But here’s the thing: I didn’t need this at all. The 9.7” iPad Pro was far and away the best tablet in the world, and upon the release of the 10.5” it became an extremely close second. Almost negligibly close.

Having used the 10.5 for a few days, but before iOS 11’s arrival, I can confidently say that if you have a 9.7” Pro, you’re good right now. You’ll probably be good for a long time. If you’re in the market for a powerful and/or stylus-optimized tablet, but don’t want to spend $700, do go and find a 9.7” Pro. You’ll love it.

I loved it. And I also love this one. The 10.5” iPad Pro is everything I loved about the 9.7”, plus a little more. I’m really glad I got it, I’m enjoying the hell out of it, but I also know I could most certainly have gone without it.

Also, if you want a tablet for just the lean-back stuff, and you want it to last many years, ignore this whole review and get one of those new vanilla iPads for a little over $300. You’ll love it.

Don’t get a Pixel C, because Google’s support it the absolute worst. (Example: In order to help me with a problem with the hinge on my Pixel C’s external hardware keyboard, they insisted I reboot my tablet and put it in safe mode. For a hinge. On a physically separate object. Sorry, no.)

*

No one needs a tablet at all. I certainly don’t. But as a lover of technology, as a big consumer of news and writing, as an artist and musician, and indeed as an autistic introvert, there’s something wonderful about these things. I’m so fortunate to be able to scrape together the means to own an object that facilitates so many of the things that bring me joy and meaning in life, and is also comfortable and appealing, such that I am drawn to it and encouraged to play, explore, create, and find a little peace.I don’t need this tablet. I’m damn glad that I have it anyway.

Hey, if you like my work, maybe you’ll think about supporting it through Patreon. That’d be cool of you.

If Trump Goes Down

Before we get too excited about what could befall President Trump as a result of this or that high crime and/or misdemeanor, I thought I’d run down a few things that might be useful to keep in mind.

Presumably, what many folks are hoping for is the impeachment of Trump and his removal from office. I share this desire to see him removed, of course, but as satisfying as his ultimate defeat and humiliation would be, there will also be unpleasant consequences.

Obviously, I’m talking about the presidency of Mike Pence. I am more or less certain that Pence would be a preferable president to Trump, if for no other reason than Pence is not a demented man-child.

But of course it also means that Pence will be far more competent in the execution of a horribly destructive right-wing agenda. Whereas Trump was happy to roll over for religious conservatives, President Pence will be the thick-necked, silver-haired paladin to usher in Revelation. Establish the Republic of Gilead, in which all the rich white dudes are now “commanders” and women are incubators.

Oh, and the cabinet. What might we expect? Say, Attorney General Ted Cruz? Education Secretary Jerry Falwell Jr.? Defense Secretary Jerry Boykin? Secretary of State John Bolton?

Vice President Mike Fucking Huckabee.

I assume Scott Pruitt stays.

And you’re likely wondering, where’s Sarah Palin?

President Mike Pence can’t abide women in his cabinet, because First Lady Karen Pence can’t be there all the time.

But hey, you think, there’s no way President Pence, forever stained by the scandal of Trump, could survive a general election against a half-acceptable Democrat.

You sure?

The closest analogue to this we have is Gerald Ford taking over for Nixon after his resignation. President Ford, of course, lost his bid for election. But not by much, and had the election happened a week or so later, it’s an even chance he would have won. It’s not a given that a destroyed administration’s back-up president is a sure bet for defeat. The silver lining to that example is that Ford was by all accounts a good and decent man, and had he won, it’s not as though much would have changed or gone off the rails.

Mike Pence is not a good and decent man, but boy does he play the hell out of one on TV. Ford, basically a good egg, couldn’t convince a sufficient percentage of voters of his good-egg-ness. Pence, a sinister, opportunistic fanatic, comes across on TV as sane, stable, comforting, and fatherly. If Trump could con enough of us to squeeze him into office, do you think the far more presentable Pence couldn’t?

And all of this is just what could happen if Trump is successfully removed from office. But it could also be that a great deal of political capitol is spent on trying to oust him, and it never takes. His base of support never wavers, Republicans in Congress remain loyal, and the public grows tired of hearing from perpetually-outraged Democrats.

This is not an argument against impeachment. Trump is dangerous in countless ways, a genuine existential threat to the country and the world. President Pence would also be a threat, but at least in ways that we can count on one or two hands. There’s a playbook for dealing with him and his type. Trump is something else.

But I also think there’s something to be said for toughing out the next three and a half years, containing Trump’s damage and allowing his idiocy to wear thin the patience of the electorate. Democrats gain in the midterms, perhaps winning one of the two houses of Congress, effectively shutting down any of Trump’s legislative goals. And in 2020 a competent Democrat can, hopefully, defeat him fair and square.

Of course, he could win then too.

So, yeah. Alright. Impeach the fucker. We’ll take on the commander next.

Please consider supporting my work through Patreon.

Immeasurable

I have lately discovered in myself a kind of sympathy with a certain flavor of religious belief and practice, which, when approached from a very particular angle, I find relatable, even laudable. To be clear, I don’t mean religion in the sense of unquestioning belief in absurd cosmological claims or even magical thinking about some silly “universal spirit” or what have you. This has more to do with things like yearning, reverence, discipline, peace, and one other thing.

That other thing, interestingly, is part and parcel with the very ideals I work to promote in my professional life advancing reason and secularism: Doubt.

It’s kind of a funny thing. I live a life positively drenched in doubt. My self-doubt is, of course, the stuff of legend, and it spills over into grave doubts about all manner of external things, from the intentions of others to the sustainability of human civilization. I’m just not so sure about any of it. No, that’s too flip. I deeply distrust all of it. Everything. It’s, as they say, crippling.

At the same time, I have a mind that strives for certainty. This is to be expected from someone with Asperger’s (which I only became aware of a few months ago), and true to the stereotype I grasp for recognizable patterns and hard-and-fast explanations for everything. Perhaps this was a primary factor as to why I found the secular-skeptic movement so appealing: Well at least I know those people are wrong!

This need for the concrete is, I think, a major reason as to why I soured on the arts about a decade ago. I didn’t feel like its benefits to humanity were sufficiently tangible. At the time I was making these considerations, things were very dark in American politics (which looks rosy compared to today), and I felt that all hands were needed on deck to fight back and make the world a better place. I did still believe that performing Shakespeare had the power to do some good, but that the effect I could have was too small, too localized. I needed to expand my do-gooder blast radius.

Politics, I thought, would bring concrete solutions, eventually. Successes there would do more than lift the spirits of a few upper-class theatre-goers; they would improve society as a whole, helping people who needed it, as opposed to just those who could afford a ticket to a play.

But I think I was missing something, something I couldn’t be expected to understand at that time in my life, at that age. I’m not sure I understand it now, but I do think I undervalued what I was doing at the time. But I couldn’t quantify it, I couldn’t see it. I doubted it.

I couldn’t live with that doubt. The irony of course is that I now utterly doubt the ability of politics and advocacy to make lasting positive change, given, you know, how things have shaken out.

But aside from the abysmal state of things in that particular arena, it remains that political advocacy is largely mechanical. Yes, of course, there is as much poetry as prose involved in the whole mess of politics and government, but all of that poetry is meant, in the end, to get some dials adjusted on the machinery of government; to get particular gears of society to move or speed up, and get others to slow or stop. Meaning can be measured.

I couldn’t measure what made a performance of Othello or As You Like It meaningful, just as I can’t measure the meaning of the songs I write and record, or even the meaning of these words. I have metrics for attention paid, surely, in clicks, downloads, listens, views, likes, shares, tweets, and all that. But there is no measuring the impact, no quantifying to what degree the world has gotten better as a result, if at all. Indeed, I have so little understanding of this that I often doubt the things I do have any meaning at all.

In the quantifiable world, the readings on the gauge are very grim. The wrong gears are moving, the right gears are being removed from the inner workings, and the dials are pointed in all the wrong directions. It is dark. And I realize this darkness is due to an emptiness, a void. It’s not a lack of good ideas or good campaign strategies. It’s a void in the human heart, a vacuum instead of open air. It is dark.

The thing about darkness, though, is that little lights become really freaking important. I’m directing a production of Into the Woods with the local university, and it might be great, or we might just eke out a passable showing by the skin of our teeth. But that’s not really the point. The point is that this group of young people are throwing their hearts and minds and energies into telling this beautiful story with this beautiful music that is full of joy and pain and fear and yearning. Whatever happens, I am certain that this show will be a little light in the dark. It already is. Before it’s even been performed, it’s already made the world a better place, made all those who have been a part of it, myself included, better people.

I can’t measure that. But only in this time of darkness do I realize how badly we need it anyway. How bad we’ve always needed it, and always will.

Here’s a thing I read recently by Dougald Hine that helped focus my thinking about this:

Art can teach us to live with uncertainty, to let go of our dreams of control. And art can hold open a space of ambiguity, refusing the binary choices with which we are often presented – not least, the choice between forced optimism and simple despair.If religion, for you, is something that is not about theological certainties or following the revealed will of the creator of the universe, but like art is about yearning, reverence, discipline, peace, and doubt, then I think I am beginning to understand that. I can’t take at all seriously any claims about some mystical being or force that has willed us into existence and interconnectedness. But I am interested in a way of thinking that yearns for this connection, that reveres the vastness of our knowledge and ignorance, that partakes in a discipline to explore and strive for this connection, that seeks and achieves moments of bliss, harmony, and peace in this practice, and that doubts every bit of it, so as to power the continuation of the cycle. Maybe that’s what faith is supposed to be about, or what it ought to be about anyway, having faith that there’s something to strive for. Against all evidence.These are strange answers. For anyone in search of solutions, they will sound unsatisfying. But I don’t think it’s possible to endure the knowledge of the crises we face, unless you are able to draw on this other kind of knowledge and practice, whether you find it in art or religion or any other domain in which people have taken the liminal seriously, generation after generation. Because the role of ritual is not just to get you into the liminal, but to give you a chance of finding your way back.

This is what the arts, the humanities, are for. Not only their products, but the practice, the making, the discipline. That’s what’s holy about one more goddamned performance of a show I’ve been doing for a year. The ritual. This is what I think I missed all those years ago, or was not yet capable of understanding. It’s what I think I misunderstood about certain key aspects of religion, and what I suspect the vast majority of religious people misunderstand, or neglect, as well.

My Aspie brain struggles painfully with this. “Why bother” is the mantra of my subconscious mind whenever I even consider undertaking some effort in writing, music, or what have you, especially given that I am not making my living this way anymore. “To what end?” asks my brain. “What good will it do, for you or anyone else?”

Daunting, invigorating, and frustrating, the only response is that it is, in every sense of the word, immeasurable.

Upsight

It might just be that there’s nowhere else for me to be. I’m just here. I’m in this place, at this time, with these people, and under these circumstances.

I have so many ideas about a better, more fulfilling, less strained situation that I might have wound up in, or that I imagine I would like to find myself in, but they are only ideas. Each, if realized, would necessarily bring with it innumerable stresses, strains, frustrations, and regrets, begetting yet more ideation about further alternate scenarios. Or maybe they wouldn’t. There’s actually no way to know.

But I do know that I am here, right now. Here and now is full of problems and pain and regrets and anxieties and miseries and dread. Here and now is also just fine. Here and now also has its joys and releases and creations and surprises and fulfillments and upsights.

And even if it didn’t, even if it doesn’t, it’s still the only here and now available to me. This is when and where I am.

I think that might be okay.

I am who I am, the amalgamation of almost 40 years of experiences—those had, avoided, and missed. I made a lot of choices, and sometimes chose not to choose. Those choices have now been made, and they’re done. Those choices, experiences, both had and not had, led to me, right now, right here, writing this.

And there’s no other way it could be. There were infinite opportunities in the past at which different choices could have been made so that something else might have been, but no longer. I am this person with these flaws and these talents and these thoughts and these inclinations and these loves and these hates and these fears and these hopes and these traumas and these disorders, in this body with its shape and color and weight and usefulness and potential and injuries and atrophies and scars and conditions and strength and genes and state of decay. I have literally nothing else to work with, nor could it be any other way. Maybe it might have been some other ways, perhaps fewer than infinite, but they are, all of them, irrelevant now.

This is where and when and who I ended up. And this is where and when and who I start with now.

I still think that might be okay.

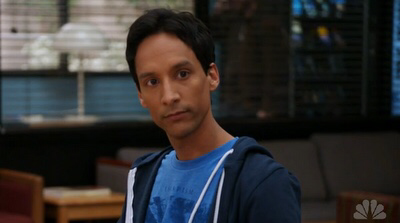

Emulating Abed

Abed Nadir from the show Community is, apparently, supposed to have Asperger’s syndrome, though it’s never stated explicitly in the show (I’m only on season 2 so maybe there’s more coming). As a newly-minted Aspie, I can’t help but look to his portrayal as a means to better understand myself. Of course I know that this is a highly fictionalized portrayal of an Aspie, and that the show itself exists in a kind of magical reality in which Abed is not only different but almost superhuman in some ways.

Abed Nadir from the show Community is, apparently, supposed to have Asperger’s syndrome, though it’s never stated explicitly in the show (I’m only on season 2 so maybe there’s more coming). As a newly-minted Aspie, I can’t help but look to his portrayal as a means to better understand myself. Of course I know that this is a highly fictionalized portrayal of an Aspie, and that the show itself exists in a kind of magical reality in which Abed is not only different but almost superhuman in some ways.

But along with being an oddball with Asperger’s, he’s also beloved. Not just in spite of, but because of his quirks, he’s adored by fans and the characters in his world. I can’t help but envy that.

One of Abed’s marquee quirks is his obsession with movies, and his desire to reenact them. Though fully secure with himself (as he even tells his friends in the first season), he nonetheless sees life through the lens of well, lenses. Movie camera lenses. In his mind, he frequently hops in and out of the personas and scenes of films.

I wonder if this isn’t itself a clue to the Aspie mind. As I grew up, and became increasingly alienated from my peers and the culture at large, I looked to the screen to instruct me on how to be. Since no one ever enrolled me in a course in “how to be a person in the world,” I had to look to the television to fill me in. How did people actually talk to each other? What did they wear? What did they value? What did they feel hostile toward? What kinds of people did they avoid or hate? What did they do with their hair? How did they stand or sit? What was funny to them? What quirky traits could be accepted or loved by others, and which ones would they reject? TV, and popular culture, was all I had to go on. I studied it when I should have been studying my schoolwork.

I think I may have had this tendency to look for role models on TV and in popular culture even before the feelings of alienation set in. This is where the overlap with Abed comes in. Because maybe if I’d never felt so utterly rejected by the normals, I’d have continued to model the behavior of fictional characters, but benignly, as a pastime that could inform creative endeavors.

So let’s look back. Let’s pop into the mind of Paul at different stages in his life to see who he considered modeling himself after and why. Maybe we…well, maybe I can learn something from the exercise.

Charlie Brown

I was not unhappy in my single-digit years, but I knew I was different. I knew I was good-different in more ways than I was bad-different, a state of mind I can barely imagine now. I knew I was smart and funny, but I also thought about things like death and futility and longing and why we bother doing the things we do. I also thought of myself as something of a screw-up, even though I can’t remember why I thought that. I mean, what had I had a chance to screw up when I was 7? I think I lost at a lot of games. And, well, anything involving sports.

Anyway, Charlie’s angst rang very true to me. His despair was like an echo of something I didn’t know I’d already been hearing in my own mind. He couldn’t quite understand why the people around him did what they did, and neither did I. I think at that age I assumed I’d eventually understand other people, and that Charlie would too.

Alex P. Keaton

Around the age of 9 or so, I decided that I would contradict by parents’ politics and declare myself a Republican, all because Alex P. Keaton on Family Ties was. Alex’s values were orthogonal to those of his family, but he was also intellectually superior and had a cutting wit. I admired that deeply, and being as short as Michael J. Fox, I appreciated this example of a loved lead male character who stood out for his brains. And his quirks. So I could be a Republican and a hyperintellectual. Wrong on both counts.

Judge Harry Stone

Harry couldn’t stop performing. He didn’t really belong on the bench, as he explained in the first episode. Technically qualified, he was the bottom of the barrel for judges, and his behavior baffled all those around him. Card tricks, dumb jokes, and a glorification of the past all served to alienate Harry from the already-bizarre world of Night Court, and yet as the show went on, his quirks went from an annoyance to a source of nurturing, his goofiness was an indication that you were safe in this place. In a crazy world, the crazy – and good – man was king.

I was funny. Right? I was smart. Wasn’t I? I was misunderstood, but given time I thought people could come around and find my oddness reassuring. I could don the hat, make the jokes, and maybe even learn to love Mel Torme.

Data

An aspirational ideation. I knew I wasn’t and could never be as intellectually and physically superior as Data the android was, but like me, he found the behavior of those around him impossible to intuit. When he tried to ape their behavior, the results were comical, and would have embarrassed anyone who was capable of feeling embarrassment.

But he wasn’t! He just kept trying! He had no feelings!

In middle and high school, the time this show was in full swing, I would have loved to have had no feelings. I couldn’t emulate Data, but only wish to be him.

Comedians

I realized that my only chance to survive middle school and high school would be through humor when my rip-off of Dana Carvey’s George Bush impression garnered laughs even from bullies and popular kids. I obviously wasn’t an athlete, nor was I sufficiently proficient in academics to ever be considered one of the “smart kids.” I could be the funny one, though.

A great deal of my pop culture study was devoted to comedians, who won approval through the inducement of laughter. I could do all of Carvey’s impressions, which came in handy. In the meantime, I absorbed every ounce of wry standup that I could, from Dennis Miller to George Carlin to David Letterman. Yes, even Seinfeld. They stood outside the world and revealed its absurdities. I stood outside the world, so I could do the same, right?

But to emulate those comedians that I watched at all hours of the night, every night, I’d need to display a level of confidence that, while probably also faked by many of those comics, I could never, ever muster. Yes, I’d develop my comedic skills, but I’d never be able to live them.

Garp, etc.

After college I got into John Irving novels. I don’t relate to wrestling, the German language, or bears, but I do relate to men who seek to be writers and have trouble making sense of their relationships to other people. I tried to imagine myself in those roles, in the life of Garp, John Wheelwright, or, even more strongly, Fred Trumper (lord, does that name not work anymore). While I certainly didn’t want to experience the tragedies that seemed to rain down on some of his characters, I did aspire to the lives of the mind they had achieved, all the while aware that they didn’t quite belong in the worlds they inhabited, due to their own failings, passions, and, yes, quirks. They were outsiders, but managed to thrive on the inside nonetheless.

Sam Seaborn, Josh Lyman, Toby Ziegler

As my thoughts moved from theatre to politics in my middle to late 20s, I saw much to envy in the fictional working lives of the characters of The West Wing. In Sam, I emulated his intense earnestness and desire to communicate that earnestness through prose. In Josh, I emulated his ability to find novel solutions to bizarre situations, despite his bafflement and his obliviousness to the effects of his own behavior. In Toby, I emulated his concision, his brusqueness, and the intentional concentration of his wit, experience, and intelligence.

But in Toby I also shared his weariness, his impatience for niceties and for the extraneous. (His advice to Will to eschew pop culture references, because they gave a speech “a shelf life of twelve minutes,” truly struck a chord with me.) And what hit me in the gut the hardest were the words of his ex-wife with whom he longed to reunite. “You’re just too sad for me, Toby.” I was too sad, too.

Blackadder, House, Sherlock

Unapologetic jerks have always held a special attraction for me in the idolization game. Not because they were jerks, per se, but because they were almost entirely uninterested in how their behavior, which included the cold analysis of the normal people around them doing ridiculous normal-person things, impacted their standing with others. If something needed saying, they’d say it. Or even if it didn’t need saying, because, well, fuck it!

Blackadder almost doesn’t count here, because he was a conniver, and an amoral one. But his verbal evisceration of those in his way (despite his failures to overcome them) was liberating to me in its own way, even though I never attempted to mimic him.

House and Sherlock, however, have been hinted to be Aspies themselves, their incredible intellects a kind of superpower that has allowed them to thrive among the normals despite the pain they cause. With all three of these characters, I envied – I envy – their shamelessness, as in, their total lack of shame for who they are. It’s not even conscious. They obviously didn’t “decide” to disavow the approval of others, it just simply isn’t a factor in their view of themselves. Forget being a clever jerk. Heck, forget being clever at all. I’d just like to have that superpower of shamelessness.

Odo

This is less about someone I wish to be like, and more about a character I suddenly understand and feel for in a striking new way.

Though he takes a humanoid form as best he can, no one thinks Odo, the changeling, really looks like them. He doesn’t understand humanoid behavior, but he does try to map it out in order to follow others’ motivations and how they lead to actions. He is impatient with the things that humanoids seem to find fulfilling and important, which to him seem pointless and wasteful. He comes off as mean when he doesn’t intend to. He craves companionship, but knows he can’t have it. And when it all comes down to it, when he’s tired of pretending to be one of the “solids,” he must – absolutely must – return to his bucket. He must resume his true liquid form, stop pretending, find total solitude, and rest.

Odo wasn’t someone I related to when Deep Space Nine first aired. But he is now.

Kirk Gleason, Abed Nadir

This brings us to today. I’ve previously written about Kirk from Gilmore Girls, how I so admire not his weirdness, per se, but his ownership of his weirdness. Do the people of Stars Hollow find Kirk a bother? Do they think he’s terribly strange? Do they find many of his actions troubling, annoying, or even destructive? Hell yes. But he doesn’t care. And he seems to fit in all the more for not caring.

Abed cares, but about the right things. He isn’t normal, and he knows it. His abnormality doesn’t bother him, nor does it bother him that people don’t get him, just as he doesn’t get them. He isn’t bothered until something about him hurts his friends or pushes them away. Then he adjusts. But not from a place of shame, but as an acknowledgement that his quirks aren’t always compatible with all the people he cares about. His adjustments are out of love, not out of shame.

“I’ve got self-esteem falling out of my butt,” says Abed. “That’s why I was willing to change for you guys. When you really know who you are and what you like about yourself, changing for other people isn’t such a big deal.”

I’m not as smart as Abed. I’m also not as overtly weird as Abed. And Abed isn’t real. But dammit, Abed, I want to live like that. Maybe one day I can be more like Abed when I grow up.

The End of the Innocence, the Wolf at the Door

I don’t want to glorify the recent past, and certainly not the crimes, both legal and moral, of the George W. Bush administration. It is difficult to overstate the damage done by that regime, the horrors of which persist in the form of various gaping, oozing wounds around the globe. Their manipulation, circumvention, and neglect of the various strands of government power were unforgivable.

I don’t want to glorify the recent past, and certainly not the crimes, both legal and moral, of the George W. Bush administration. It is difficult to overstate the damage done by that regime, the horrors of which persist in the form of various gaping, oozing wounds around the globe. Their manipulation, circumvention, and neglect of the various strands of government power were unforgivable.

And yet as we await the inauguration of Donald Trump, there is something halcyon about the years between 2001 and 2008. How could that be? With the Bush years, we saw the cynically power-mad invasion of a bystander nation, the bizarre theocratic and apocalyptic delusions of Christianists, the government sanction of torture and the wriggling out of international agreements against inhumane practices, the pillaging and demolition of the world financial system, the jaw-dropping disinterest in the destruction of New Orleans, the refusal to act on the planetary threat of climate change, and the million little ways that rights were eroded, facts were downplayed, crises were ignored, and nativist paranoias were stoked for political benefit.

And yet I’d reinstate Bush, Cheney, and the whole crew of bastards all over again if it meant we could avoid a Trump presidency. Why? Rather hyperbolic, don’t you think?

Here is where, perhaps, I am guilty of tinting my spectacles with a rosy hue. Because it seems to me that, most of the time, when norms, laws, or basic moral tenets were violated, it was done within the framework of a system that, even when abused, remained more or less intractable. In order to torture, the lawyers had to twist themselves into knots to legally justify it. When Iraq was invaded for absolutely no reason based in reality, diplomatic boxes were checked and approval was granted by great deliberative bodies. Even the failed schemes of the era were done within this framework: Bush and his allies wanted so badly to privatize Social Security, but even with their near total control of the federal government, could not muster the political force to make it happen.

They bent some of the beams and they loosened many of the rivets, but the framework held. It held so well that they were able to be defeated electorally, by congressional Democrats in 2006 (though it was to be disturbingly short-lived), and by Barack Obama in 2008 and 2012.

But this framework is imaginary, of course. And I don’t just mean that it’s a metaphor. I mean that the system itself is imaginary, a social construction, in the same way that money is. “We hold these truths to be self-evident” and all that. We collectively decide that we’re all going to abide by these rules, live within the framework. We might skirt this rule, bend that one, and others break altogether. We may break rules entirely and may lie about what we’ve done. But in all of those cases, we all acknowledge that the rules are there. The Constitution, the law, and even the unwritten norms of a democratic republic. Crimes, abuses, and neglect all happen within the framework that we all pretend is there.

Donald Trump, I fear, does not acknowledge the framework. He seems to refuse to accept its legitimacy, he makes little pretense of playing along. He may even be intellectually unable to grasp it, and in that way, he is not unlike an embodiment of the state of nature. We humans take very seriously the sovereignty of our homes, and take it for granted that our fences and walls and property lines clearly delineate our inviolable domains, but other species do not. They can’t possibly understand these concepts, and if they could, they’d certainly not take them seriously or feel beholden to them.

The social construction of our system of government, our framework, is like a home, and Trump is a wolf at the door. The wolf doesn’t know or care that you might “own” the plot of land upon which your house sits. If he can get in, he won’t feel any compunction to respect the integrity of the house, nor the lives of the people inside.

Warnings about the potentially dire consequences of a Trump presidency are not new, of course. Alarms are sounding all over the place. But even so, I read and hear a great deal of very smart, experienced people saying that Trump and his ascendant marauders will find it rather difficult to enact the kind of sweeping, draconian changes they seek. The public will have to be sold on much of it, they say. Major projects will have to be funded. The vast, sprawling federal bureaucracy will not be so easy to turn on a dime to pursue ends counter to their very reasons for being. The military will outright refuse to execute some of the more horrific orders that Trump has promised to issue.

I am not so confident. Remember back to the Bush administration, where at the very least efforts were made to justify offenses within the structure of the framework. The politicking, the legal gymnastics, the feigned diplomacy, all of it at least acknowledged there was a system to abuse. Even for those who considered the rule of law subservient to the authority of their religion were at least subject to a different framework, the even-more-imaginary dictates of their God.

My fear is that a Trump administration will not respect this imaginary framework. They will act without feeling the need to justify through legal interpretation or moral imperative. They will simply act. The Republican Party has shown itself, conclusively, to be acquiescent to Trump, and they will now control all three branches of federal power. If they choose to reject the framework, there is literally nothing they can’t do. The Democrats in Congress might have an investigation? Ignore it. Accused of breaking the law? We are the law. The public is unhappy? Lie to them. Scare them. Or don’t. What can they do? Vote you out? Elections are as meaningless now as everything else.

I fear that future generations will look back on this time of transition as the end of an innocence, when we humans thought we had built a stable, robust political and social system that existed only in our heads. How naive we were, to think that we could head off utter disaster because some rules we’d written down somewhere would serve as a bulwark against those with voracious appetites for power and wealth. That we could get the wolf to leave our doorstep by pushing a strongly-worded note through the mail slot.

Don’t you know you’re not allowed to eat the people in this house, Mister Wolf? Don’t you know it’s against the rules? Now don’t make me come out there and explain these rules to you.

Oh, alright, if I must. But you have to promise me you won’t eat me while I’m talking to you.

Please consider supporting my work through Patreon. Image by ElenaTurtle (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0).

This Situation is Awkward, and I Can't Stand Being In It

I don’t know how to react to it, and I’m worried that I may not feel enough at the time to make the right sorts of expressions on my face. How am I supposed to look? Am I supposed to tear up? Eugh. The situation is awkward, and I can’t stand being in it.This is the nearly daily experience of having Asperger’s syndrome, which I was diagnosed with this past August at the age of 38. Shortly after finding out, I read a book called Asperger’s on the Inside by Michelle Vines, a woman who around the same age discovered that the difficulties she had wrestled with her whole life were also attributable to Asperger’s. A friend of mine recommended her as a potential source for perspective after she was a guest on my organization’s podcast Point of Inquiry, and I must say, so many of Vines’ experiences and challenges mirror my own.

Not all, of course. On the whole, I’d say Vines is more interested in assertively establishing friendships and social groups than I am. In her efforts to do so, yes, there are some truly eye-opening similarities between us, but I, so often being burned by the social world, have opted out. She took a different approach, seeing her social struggles as a problem to solve, a puzzle. I wish I had more of an attitude like that.

Rather than go into a deep review of her book, which as you can imagine I mostly enjoyed (though I thought some of the attempts at humor were a little forced), I’d simply highlight some passages that were meaningful to me and reflect on them. This isn’t by any means exhaustive, but a selection of highlights that I felt I had something to say about.

On Aspie emotions:

Another example [of the challenges Aspies face] is the intense difficulties we Aspies can have with emotional regulation, which I’ve experienced firsthand. Emotional regulation is a technical term I’ve seen in online articles—sorry to feed you technobabble. In simple terms, it means that when we feel an extreme emotion, such as sadness, we can stay in that emotionally extreme state for a long time with little ability to make the feelings go away.This is definitely true for me. Often this manifests just as you’d expect; as panic, intense anxiety, or overwhelming depression (or all of the above).

Sometimes it expresses itself far more deeply within me, which is often interpreted as my holding something resembling a grudge, “dwelling,” or rudely closing off entirely. But the reality is that sometimes the feelings are so powerful or painful, the cognitive effort required to just stay afloat means I have to shut off everything external, and present a kind of low, blank disposition toward others. It’s almost as though I’m booting into “safe mode” so I can devote all my processing power to working through my overwhelming feelings. I’m sure it looks weird.

On appearing normal:

So, as you may have guessed, I, like many Aspies, was not born with an interest in fashion and clothing, or at least it wasn’t there when I was young. In my childhood and early teen years, I remember being teased occasionally on free dress days for wearing the odd daggy[19] thing my mum bought me. No one told me that you don’t tuck your T-shirt into your jeans! What’s wrong with black shoes and white trousers? Or the fluorescent-pink parachute tracksuit that my mum got me for my birthday?Oh how I wished I’d had some guidance on this kind of basic social blending knowledge, just an early seed of understanding that other people would care so goddamn much about this kind of thing, and that in order to get through the day with one obstacle fewer, it’d be wise to just check these boxes.

But no one told me. No one told me what to wear, and I didn’t care in the least, and was in fact barely aware of what I was wearing, so people made fun of my clothes. No one told me what to do with one’s hair, so it got too long and out of control, and people made fun of my hair. In southern New Jersey – which is largely populated by olive-skinned, beach-loving people of Italian descent – having a tan was considered table stakes for presentability. But I abhorred the sun, the heat, and the overall beach culture, and my genes had given me extremely pale skin that burns very easily, so I was made fun of for that all the time as well.

Also, I’m rather short, but I guess there was nothing I could do about that, though my grandmother used to tell me I failed to become tall because I refused to hang upside-down by my knees on the jungle gym. So I blamed myself for being short, too.

On communicating one’s challenges:

I started going through possible ways she and my father-in-law could respond [to my difficulties with people]. Was I going to get a talk on how I was “viewing everything wrong” or how I “need to change X and just get in there and do Y and stop overthinking it”? I guess I expect these sorts of comments, because they’re the usual reaction I get from people when I make little hints that something might be hard for me. People so often downplay my issues. “Everyone else deals with Z, so you should be fine dealing with Z too.” “Nobody likes working, but we all do it.” So that’s what I waited to hear.Asperger’s or not, this is a common refrain whenever I’ve discussed my difficulties in school, in jobs, or anywhere else. “Everyone feels that way sometimes.” The implication is, of course, that since everyone else deals with it, and yet here I am particularly aggrieved by it, there’s something wrong with me, I’m especially weak or lazy or overly sensitive for no good reason. I’m having trouble, and it’s my own fault for being effected by it.

But no, everyone doesn’t feel like this. Not like I do.

It’s interesting that I made the automatic assumption that I need to debate to justify my views and people won’t naturally respect my opinions and feelings. Being me and explaining myself has typically been so exasperating.Preach. This is a big reason why I think I overshare on my blog and on Twitter; it’s where I can, at my own speed, work through my thoughts and feelings and communicate in far more precise way. This isn’t to say that it’s always successful. But it’s better than most other means of communicating for me.

On processing information:

I am astoundingly bad with directions. I have just the worst time navigating through and orienting myself in space. This not only applies to things like how to drive from one location to another, but to things like depth perception, where parallel parking induces sweats, or playing video games (especially first-person perspective games) where I am constantly confused about my location in relation to everything else going on.

And when directions are explained to me verbally, my brain simply can’t process them. I try, I try very hard. I understand the meaning of the words being said to me, but it’s almost as though my brain immediately garbles the words so that as a whole, they are just gibberish. Even just being given a short list of basic instructions or tasks is a big mental load for me, and I have to concentrate intensely, repeat things out loud, and almost rehearse the actions in my head to be sure they actually make sense to me. Imagine how frustrating that is for my wife, who before this Asperger’s business couldn’t help but assume I just wasn’t listening.

Here’s Vines on this topic:

Sometimes, we just can’t function with so much sensory and verbal input and real-time speed. Or if the topic is not of interest, it may be hard for us to keep our focus on it in the face of other input. And I particularly wanted to bring it up in this chapter because, for such a long time, I really thought it was some sort of memory glitch that I had, and I used to kick myself for how bad I was at grasping and remembering the little details that people would tell me about themselves. I must be selfish, right? To never be able to remember the details of other people’s lives? Everyone else cares enough about other people to remember that stuff. What was wrong with me? It took me a long time to figure that one out—and a lot of guilt, I might add. So, when does this so-called memory issue affect me? Well, unfortunately, I can be pretty bad with directions.Yep. And I’m also the same with details of others’ lives. I care about other people, of course, but I also frankly suffer from an acute lack of curiosity about those details. So they never, ever stick.

On being outdoors:

How many times have people said to me, “It’s a beautiful sunny day,” or, “I hope the sun will be out tomorrow,” and I’ve privately thought, “I really hope not! I hope for a pleasant, overcast day. Please give me miserable weather! The kind that makes me relax and feel at peace.” I know that other people love frolicking out in the sun and enjoying the brightness of summer, but for me, having that direct sun on me drains my energy and has always made me, subconsciously, that little bit tenser.Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes. See my essay on the seasons from a couple of years ago, long before I knew anything about my Asperger’s.

On coping in the workplace:

I’ve had some jobs I’ve deeply, deeply hated. I know, everyone has. But while these jobs caused me unspeakable anxiety, stress, and depression, I’ve often found that I couldn’t communicate to others why I was so unhappy. When asked, “What didn’t you like about your job?” I’d find myself almost inventing reasons, or exaggerating small grievances, because I couldn’t find a way to express what was really wrong. Here’s a window into that from Vines’ own work experiences:

Within a month of starting, I began to dread going to work. On the train heading in, I would have dreams about the train crashing and sending me to hospital or the city being bombed (preferably overnight while empty of people!). I became depressed and numb Monday to Friday and spent most of Sunday crying, feeling ill because I had to go to work again the next day. I was in no way “okay.”This all rings very true. In face, the Sunday evening stress sessions became so common that my wife gave them a name: The SNAS (pronounced “snazz”): Sunday Night Anxiety Show.

When I mentioned it to people, I frequently got nonchalant replies such as, “Yeah, nobody likes working, but we all have to do it.” So after a while, I learnt to stop complaining. At the time, I had no idea that I had Asperger’s. And while I always had the sense that it must be worse for me than for other people, I couldn’t justify that feeling. …Take special note of that last thought, about dealing with unfamiliar people, and then consider that I have spent most of my post-theatre career as a PR director. Yeah, great move, right?Every place I worked, I had an overwhelming desire to get out of there. I had trouble focusing on the work and interacting with people at the same time. I would feel frustrated or angry inside and often felt like snapping at people (although I didn’t). I dreaded having to do tasks that involved dealing with unfamiliar people. It exhausted me.

The paragraph continues:

I disliked having to figure out how to do new things. Most of the time, I was given new things constantly, and I really had to force myself to start them. I had trouble remembering verbal instructions and needed to write things down. … In hindsight, perhaps I didn’t do and say the right things to project the best image of myself and promote myself to others. I needed to do things my way and plan my own time. Being micromanaged by others was too stressful. I felt sick and started to hate going to work. All I could conclude was that the common factor was me.There is a terrible fear I have of being scrutinized by coworkers or bosses. Like Vines, I want them to trust I will get the job done, but I can’t bear to have my methods or practices judged. Why? Because I always assume I’m doing it wrong, getting away with something.

Dr. Loveland, who diagnosed me, explained that these workplace experiences I describe weren’t uncommon for people with Asperger’s and that she’d heard stories like mine before. She explained to me that that “sick” feeling I talked of was the result of bottling up frustration and anxiety all day, every day. Built up over time, I suppose it manifests physiologically, causing me stomach upset, low weight, and a general feeling of being unwell.And this is why I spent my aforementioned post-theatre career in a state of sub-optimal health, to say the least. It got so bad when I worked for the 2008 Hillary Clinton presidential campaign, with the 15-hour days of intense stress, scrutiny, and pressure while packed in a giant room with people (many of whom were themselves very intense), I fell apart. It resulted in a trip to the emergency room, a scare that I might have brain cancer (I didn’t), neurological problems that manifested in my limbs and fingers, and a full-body muscle spasm or tic that I have to this day.

Had I known I had Asperger’s then, I never would have taken that job. Or I would have at least found another way to do it.

On talking to people:

I don’t usually want to, unless I have a specific reason to be curious about them, or I have some kind of investment in them, like a close friend or family member. So I don’t talk a lot around people I don’t know well, unless of course I’m the only one there, or I feel there’s an expectation, and then I blather like an imbecile.

And as I mentioned earlier, a big part of the problem is that no matter how much I try, no matter how much I know I should, I simply can’t muster any curiosity about other people. And that’s not a good start for making small talk.

Which I hate.

Here’s Vines on that:

We find [small talk] mind numbing, lacking in content, and tiresome, because we’re mainly tuning into the details and not focusing on the social or emotional purpose of the conversation, probably in the same way that typical people can find our conversation intense, overly technical, detailed, and exhausting. For me, it’s hard to come up with anything to say in a conversation that, on the whole, seems lacking in purpose.I have frustrated many a significant-other over this. “Why were you so quiet?” and “Why didn’t you ask anybody any questions?” Well, because I didn’t have any questions. I didn’t realize there was a kind of social ritual being played out.

So one tactic I might use to fill verbal space is to talk about my own take on a topic, or my own experience, and I find that this very often falls rather flat. Again, turns out it’s because I haven’t tuned into what the whole ritual is about.

As an Aspie it feels natural to respond to a conversation by relating our experiences, especially when the topic is emotional. We’re basically saying, “I know how you feel/what you are experiencing because I’ve had a feeling/experience like that myself.” To us, it’s a display that we’re actually connecting to a person’s feelings and are bonding with them. However, typical people don’t need to have had a similar experience to feel what a friend might be feeling, and they don’t need to relate that experience to show they understand. Changing the topic this way on occasion is fine, but when we do it frequently, all a typical person hears is, “me me me.”Alas.

On self acceptance:

I am not close to being in the place Vines has achieved. But I aspire.

What I really feel the need to say here is that there is nothing wrong with me. I’m just different. And any difficulties I have are the result of trying to live in a world where everyone around me is so different from me, not because I myself am faulty. I think Tony Attwood hit the nail on the head when he said, “People don’t suffer from Asperger’s Syndrome. They suffer from other people.” I’m not “wrong.” I’m everything I’m supposed to be and more. But both the social world and the business world that I live in aren’t set up for someone like me. I’m the proverbial square peg trying to fit in a round hole, and I can’t function effectively like this. I have so much potential to be useful, creative, even ingenious. The world just has to find a way to utilize me better. …The world isn’t set up for me. And I can’t make the world change for me. But maybe I can stop attacking myself over the dissonance I perceive. I play my song, you play yours. I hope I can.…

It doesn’t matter what label you carry or what cause you stand for. If you approach the world with an assured attitude and pride in who you are, other people will love and respect you for it. It’s only when you hide things about yourself that you convey that something is wrong or shameful about you that needs to be hidden.

If you like my work, please consider supporting it through Patreon.

Impact Without Agency: On the Peculiar Character of 2016

The skeptic in me – the one whose rationality was inspired by Carl Sagan, the one that must force himself to be politic when talk of God, psychic abililities, or superstitions come up, the one whose actual job is to be the voice of an entire skeptics’ organization – knows, for certain, that there is no curse attached to the calendar year 2016. There is nothing special about this particular trip around the Sun for our planet, nor is there any negative “energy” or force particular to this year that makes it any more or less eventful or tragic. 2016 has no magic power for killing celebrities.

I know that tens of thousands of people die every day. (And as my podcast co-host Brian Hogg is wont to remind us, the real tragedy there is that we never know that any of them ever existed.) And celebrities also die. That they seem to be dropping at a higher rate this year is attributable to any number of banal things.

Terrible national and global events happen in every year. Is it’s not political upheaval in one country its a natural disaster in another. Usually it’s both. 2016 may seem more tumultuous simply because this time it’s happening to us in the United States, you know, the Only Country That Really Matters™.

And of course, we all lead lives of varying degrees of drama, triumph, and misery. We all go through major life changes, endure challenges, learn new things about ourselves, and all the while the people we love do too. In some years more, in some years less.

And yet.

I had been thinking about writing about this subject – the “cursed” 2016, the Year of the Dumpster Fire – for some time, but I kept holding off, guessing that something might yet still happen, some big kick in the face, punch in the gut, or other metaphorical impact with a body part. I or a family member might find our lives upended, another beloved public figure might unexpectedly drop dead, another world event might Change Everything once again.