Books: Too Sexy for Words

I love physical books. I also love my Kindle Paperwhite and I also love my iPad. All of them are wonderful objects, and oh yes, they allow me to read. The reading, you see, is the important part.

You wouldn’t know it, though, from the testimonials of some who dismiss ebooks and swear only by physical codices. In her essay in The Guardian, Paula Cocozza gives a slight nod to the pleasures of reading on paper versus screens, which I do not disagree with, but much of the column is a celebration of the physical book, not for its contents, but for its physical properties and how they can be creatively embellished upon:

Once upon a time, people bought books because they liked reading. Now they buy books because they like books. “All these people are really thinking about how the books are – not just what’s in them, but what they’re like as objects,” says Jennifer Cownie, who runs the beautiful Bookifer website and the Cownifer Instagram, which match books to decorative papers, and who bought a Kindle but hated it. Summerhayes thinks that “people have books in their house as pieces of art … Everyone wants sexy-looking books,” she says.Do they? And if they do, well, so what? People want sexy-looking everything!

This obviously doesn’t speak to the superiority of books over ebooks as means to reading. It’s a display of fetishism for a product, the reduction of the book from medium to fashion item. If overly expensive smartphones are gaudy status symbols, then what do you call artsy displays of shelved volumes that are never actually opened?

I’ve actually come to appreciate physical books more than ever lately as I have tried very hard to steer my attention away from the constant stress and panic of social media. Kindles are actually great for that all on their own, since they can’t do much of anything other than display, notate, research, or purchase book content. (Oh, and they’re self-illuminating, which is a huge leg up on mere paper.) But there is that one additional step of removal from the online swarm that one can achieve with a physical book that is often deeply refreshing, and I am finding at times necessary. I am re-learning to treasure that.

And as much as I do appreciate a book’s physical properties (yes I am one of those “I love the smell of old books” weirdos), I don’t concern myself with books as art objects or accessories. My positive associations with books as objects, the reason I like the smell of paper, dust, and glue, has almost entirely to do with what’s inside them, how the words affect me, and how the experience of reading saves me from the world.

It’s fine to argue that physical books are better than ebooks. But if all you’re talking about is which makes for a better subject for photographic projects, you’re missing the whole point.

# # #

Because you like me so much, please consider supporting my work financially through Patreon.

Immeasurable

I have lately discovered in myself a kind of sympathy with a certain flavor of religious belief and practice, which, when approached from a very particular angle, I find relatable, even laudable. To be clear, I don’t mean religion in the sense of unquestioning belief in absurd cosmological claims or even magical thinking about some silly “universal spirit” or what have you. This has more to do with things like yearning, reverence, discipline, peace, and one other thing.

That other thing, interestingly, is part and parcel with the very ideals I work to promote in my professional life advancing reason and secularism: Doubt.

It’s kind of a funny thing. I live a life positively drenched in doubt. My self-doubt is, of course, the stuff of legend, and it spills over into grave doubts about all manner of external things, from the intentions of others to the sustainability of human civilization. I’m just not so sure about any of it. No, that’s too flip. I deeply distrust all of it. Everything. It’s, as they say, crippling.

At the same time, I have a mind that strives for certainty. This is to be expected from someone with Asperger’s (which I only became aware of a few months ago), and true to the stereotype I grasp for recognizable patterns and hard-and-fast explanations for everything. Perhaps this was a primary factor as to why I found the secular-skeptic movement so appealing: Well at least I know those people are wrong!

This need for the concrete is, I think, a major reason as to why I soured on the arts about a decade ago. I didn’t feel like its benefits to humanity were sufficiently tangible. At the time I was making these considerations, things were very dark in American politics (which looks rosy compared to today), and I felt that all hands were needed on deck to fight back and make the world a better place. I did still believe that performing Shakespeare had the power to do some good, but that the effect I could have was too small, too localized. I needed to expand my do-gooder blast radius.

Politics, I thought, would bring concrete solutions, eventually. Successes there would do more than lift the spirits of a few upper-class theatre-goers; they would improve society as a whole, helping people who needed it, as opposed to just those who could afford a ticket to a play.

But I think I was missing something, something I couldn’t be expected to understand at that time in my life, at that age. I’m not sure I understand it now, but I do think I undervalued what I was doing at the time. But I couldn’t quantify it, I couldn’t see it. I doubted it.

I couldn’t live with that doubt. The irony of course is that I now utterly doubt the ability of politics and advocacy to make lasting positive change, given, you know, how things have shaken out.

But aside from the abysmal state of things in that particular arena, it remains that political advocacy is largely mechanical. Yes, of course, there is as much poetry as prose involved in the whole mess of politics and government, but all of that poetry is meant, in the end, to get some dials adjusted on the machinery of government; to get particular gears of society to move or speed up, and get others to slow or stop. Meaning can be measured.

I couldn’t measure what made a performance of Othello or As You Like It meaningful, just as I can’t measure the meaning of the songs I write and record, or even the meaning of these words. I have metrics for attention paid, surely, in clicks, downloads, listens, views, likes, shares, tweets, and all that. But there is no measuring the impact, no quantifying to what degree the world has gotten better as a result, if at all. Indeed, I have so little understanding of this that I often doubt the things I do have any meaning at all.

In the quantifiable world, the readings on the gauge are very grim. The wrong gears are moving, the right gears are being removed from the inner workings, and the dials are pointed in all the wrong directions. It is dark. And I realize this darkness is due to an emptiness, a void. It’s not a lack of good ideas or good campaign strategies. It’s a void in the human heart, a vacuum instead of open air. It is dark.

The thing about darkness, though, is that little lights become really freaking important. I’m directing a production of Into the Woods with the local university, and it might be great, or we might just eke out a passable showing by the skin of our teeth. But that’s not really the point. The point is that this group of young people are throwing their hearts and minds and energies into telling this beautiful story with this beautiful music that is full of joy and pain and fear and yearning. Whatever happens, I am certain that this show will be a little light in the dark. It already is. Before it’s even been performed, it’s already made the world a better place, made all those who have been a part of it, myself included, better people.

I can’t measure that. But only in this time of darkness do I realize how badly we need it anyway. How bad we’ve always needed it, and always will.

Here’s a thing I read recently by Dougald Hine that helped focus my thinking about this:

Art can teach us to live with uncertainty, to let go of our dreams of control. And art can hold open a space of ambiguity, refusing the binary choices with which we are often presented – not least, the choice between forced optimism and simple despair.If religion, for you, is something that is not about theological certainties or following the revealed will of the creator of the universe, but like art is about yearning, reverence, discipline, peace, and doubt, then I think I am beginning to understand that. I can’t take at all seriously any claims about some mystical being or force that has willed us into existence and interconnectedness. But I am interested in a way of thinking that yearns for this connection, that reveres the vastness of our knowledge and ignorance, that partakes in a discipline to explore and strive for this connection, that seeks and achieves moments of bliss, harmony, and peace in this practice, and that doubts every bit of it, so as to power the continuation of the cycle. Maybe that’s what faith is supposed to be about, or what it ought to be about anyway, having faith that there’s something to strive for. Against all evidence.These are strange answers. For anyone in search of solutions, they will sound unsatisfying. But I don’t think it’s possible to endure the knowledge of the crises we face, unless you are able to draw on this other kind of knowledge and practice, whether you find it in art or religion or any other domain in which people have taken the liminal seriously, generation after generation. Because the role of ritual is not just to get you into the liminal, but to give you a chance of finding your way back.

This is what the arts, the humanities, are for. Not only their products, but the practice, the making, the discipline. That’s what’s holy about one more goddamned performance of a show I’ve been doing for a year. The ritual. This is what I think I missed all those years ago, or was not yet capable of understanding. It’s what I think I misunderstood about certain key aspects of religion, and what I suspect the vast majority of religious people misunderstand, or neglect, as well.

My Aspie brain struggles painfully with this. “Why bother” is the mantra of my subconscious mind whenever I even consider undertaking some effort in writing, music, or what have you, especially given that I am not making my living this way anymore. “To what end?” asks my brain. “What good will it do, for you or anyone else?”

Daunting, invigorating, and frustrating, the only response is that it is, in every sense of the word, immeasurable.

Upsight

It might just be that there’s nowhere else for me to be. I’m just here. I’m in this place, at this time, with these people, and under these circumstances.

I have so many ideas about a better, more fulfilling, less strained situation that I might have wound up in, or that I imagine I would like to find myself in, but they are only ideas. Each, if realized, would necessarily bring with it innumerable stresses, strains, frustrations, and regrets, begetting yet more ideation about further alternate scenarios. Or maybe they wouldn’t. There’s actually no way to know.

But I do know that I am here, right now. Here and now is full of problems and pain and regrets and anxieties and miseries and dread. Here and now is also just fine. Here and now also has its joys and releases and creations and surprises and fulfillments and upsights.

And even if it didn’t, even if it doesn’t, it’s still the only here and now available to me. This is when and where I am.

I think that might be okay.

I am who I am, the amalgamation of almost 40 years of experiences—those had, avoided, and missed. I made a lot of choices, and sometimes chose not to choose. Those choices have now been made, and they’re done. Those choices, experiences, both had and not had, led to me, right now, right here, writing this.

And there’s no other way it could be. There were infinite opportunities in the past at which different choices could have been made so that something else might have been, but no longer. I am this person with these flaws and these talents and these thoughts and these inclinations and these loves and these hates and these fears and these hopes and these traumas and these disorders, in this body with its shape and color and weight and usefulness and potential and injuries and atrophies and scars and conditions and strength and genes and state of decay. I have literally nothing else to work with, nor could it be any other way. Maybe it might have been some other ways, perhaps fewer than infinite, but they are, all of them, irrelevant now.

This is where and when and who I ended up. And this is where and when and who I start with now.

I still think that might be okay.

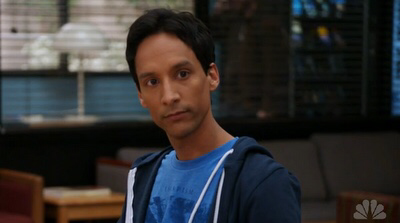

Emulating Abed

Abed Nadir from the show Community is, apparently, supposed to have Asperger’s syndrome, though it’s never stated explicitly in the show (I’m only on season 2 so maybe there’s more coming). As a newly-minted Aspie, I can’t help but look to his portrayal as a means to better understand myself. Of course I know that this is a highly fictionalized portrayal of an Aspie, and that the show itself exists in a kind of magical reality in which Abed is not only different but almost superhuman in some ways.

Abed Nadir from the show Community is, apparently, supposed to have Asperger’s syndrome, though it’s never stated explicitly in the show (I’m only on season 2 so maybe there’s more coming). As a newly-minted Aspie, I can’t help but look to his portrayal as a means to better understand myself. Of course I know that this is a highly fictionalized portrayal of an Aspie, and that the show itself exists in a kind of magical reality in which Abed is not only different but almost superhuman in some ways.

But along with being an oddball with Asperger’s, he’s also beloved. Not just in spite of, but because of his quirks, he’s adored by fans and the characters in his world. I can’t help but envy that.

One of Abed’s marquee quirks is his obsession with movies, and his desire to reenact them. Though fully secure with himself (as he even tells his friends in the first season), he nonetheless sees life through the lens of well, lenses. Movie camera lenses. In his mind, he frequently hops in and out of the personas and scenes of films.

I wonder if this isn’t itself a clue to the Aspie mind. As I grew up, and became increasingly alienated from my peers and the culture at large, I looked to the screen to instruct me on how to be. Since no one ever enrolled me in a course in “how to be a person in the world,” I had to look to the television to fill me in. How did people actually talk to each other? What did they wear? What did they value? What did they feel hostile toward? What kinds of people did they avoid or hate? What did they do with their hair? How did they stand or sit? What was funny to them? What quirky traits could be accepted or loved by others, and which ones would they reject? TV, and popular culture, was all I had to go on. I studied it when I should have been studying my schoolwork.

I think I may have had this tendency to look for role models on TV and in popular culture even before the feelings of alienation set in. This is where the overlap with Abed comes in. Because maybe if I’d never felt so utterly rejected by the normals, I’d have continued to model the behavior of fictional characters, but benignly, as a pastime that could inform creative endeavors.

So let’s look back. Let’s pop into the mind of Paul at different stages in his life to see who he considered modeling himself after and why. Maybe we…well, maybe I can learn something from the exercise.

Charlie Brown

I was not unhappy in my single-digit years, but I knew I was different. I knew I was good-different in more ways than I was bad-different, a state of mind I can barely imagine now. I knew I was smart and funny, but I also thought about things like death and futility and longing and why we bother doing the things we do. I also thought of myself as something of a screw-up, even though I can’t remember why I thought that. I mean, what had I had a chance to screw up when I was 7? I think I lost at a lot of games. And, well, anything involving sports.

Anyway, Charlie’s angst rang very true to me. His despair was like an echo of something I didn’t know I’d already been hearing in my own mind. He couldn’t quite understand why the people around him did what they did, and neither did I. I think at that age I assumed I’d eventually understand other people, and that Charlie would too.

Alex P. Keaton

Around the age of 9 or so, I decided that I would contradict by parents’ politics and declare myself a Republican, all because Alex P. Keaton on Family Ties was. Alex’s values were orthogonal to those of his family, but he was also intellectually superior and had a cutting wit. I admired that deeply, and being as short as Michael J. Fox, I appreciated this example of a loved lead male character who stood out for his brains. And his quirks. So I could be a Republican and a hyperintellectual. Wrong on both counts.

Judge Harry Stone

Harry couldn’t stop performing. He didn’t really belong on the bench, as he explained in the first episode. Technically qualified, he was the bottom of the barrel for judges, and his behavior baffled all those around him. Card tricks, dumb jokes, and a glorification of the past all served to alienate Harry from the already-bizarre world of Night Court, and yet as the show went on, his quirks went from an annoyance to a source of nurturing, his goofiness was an indication that you were safe in this place. In a crazy world, the crazy – and good – man was king.

I was funny. Right? I was smart. Wasn’t I? I was misunderstood, but given time I thought people could come around and find my oddness reassuring. I could don the hat, make the jokes, and maybe even learn to love Mel Torme.

Data

An aspirational ideation. I knew I wasn’t and could never be as intellectually and physically superior as Data the android was, but like me, he found the behavior of those around him impossible to intuit. When he tried to ape their behavior, the results were comical, and would have embarrassed anyone who was capable of feeling embarrassment.

But he wasn’t! He just kept trying! He had no feelings!

In middle and high school, the time this show was in full swing, I would have loved to have had no feelings. I couldn’t emulate Data, but only wish to be him.

Comedians

I realized that my only chance to survive middle school and high school would be through humor when my rip-off of Dana Carvey’s George Bush impression garnered laughs even from bullies and popular kids. I obviously wasn’t an athlete, nor was I sufficiently proficient in academics to ever be considered one of the “smart kids.” I could be the funny one, though.

A great deal of my pop culture study was devoted to comedians, who won approval through the inducement of laughter. I could do all of Carvey’s impressions, which came in handy. In the meantime, I absorbed every ounce of wry standup that I could, from Dennis Miller to George Carlin to David Letterman. Yes, even Seinfeld. They stood outside the world and revealed its absurdities. I stood outside the world, so I could do the same, right?

But to emulate those comedians that I watched at all hours of the night, every night, I’d need to display a level of confidence that, while probably also faked by many of those comics, I could never, ever muster. Yes, I’d develop my comedic skills, but I’d never be able to live them.

Garp, etc.

After college I got into John Irving novels. I don’t relate to wrestling, the German language, or bears, but I do relate to men who seek to be writers and have trouble making sense of their relationships to other people. I tried to imagine myself in those roles, in the life of Garp, John Wheelwright, or, even more strongly, Fred Trumper (lord, does that name not work anymore). While I certainly didn’t want to experience the tragedies that seemed to rain down on some of his characters, I did aspire to the lives of the mind they had achieved, all the while aware that they didn’t quite belong in the worlds they inhabited, due to their own failings, passions, and, yes, quirks. They were outsiders, but managed to thrive on the inside nonetheless.

Sam Seaborn, Josh Lyman, Toby Ziegler

As my thoughts moved from theatre to politics in my middle to late 20s, I saw much to envy in the fictional working lives of the characters of The West Wing. In Sam, I emulated his intense earnestness and desire to communicate that earnestness through prose. In Josh, I emulated his ability to find novel solutions to bizarre situations, despite his bafflement and his obliviousness to the effects of his own behavior. In Toby, I emulated his concision, his brusqueness, and the intentional concentration of his wit, experience, and intelligence.

But in Toby I also shared his weariness, his impatience for niceties and for the extraneous. (His advice to Will to eschew pop culture references, because they gave a speech “a shelf life of twelve minutes,” truly struck a chord with me.) And what hit me in the gut the hardest were the words of his ex-wife with whom he longed to reunite. “You’re just too sad for me, Toby.” I was too sad, too.

Blackadder, House, Sherlock

Unapologetic jerks have always held a special attraction for me in the idolization game. Not because they were jerks, per se, but because they were almost entirely uninterested in how their behavior, which included the cold analysis of the normal people around them doing ridiculous normal-person things, impacted their standing with others. If something needed saying, they’d say it. Or even if it didn’t need saying, because, well, fuck it!

Blackadder almost doesn’t count here, because he was a conniver, and an amoral one. But his verbal evisceration of those in his way (despite his failures to overcome them) was liberating to me in its own way, even though I never attempted to mimic him.

House and Sherlock, however, have been hinted to be Aspies themselves, their incredible intellects a kind of superpower that has allowed them to thrive among the normals despite the pain they cause. With all three of these characters, I envied – I envy – their shamelessness, as in, their total lack of shame for who they are. It’s not even conscious. They obviously didn’t “decide” to disavow the approval of others, it just simply isn’t a factor in their view of themselves. Forget being a clever jerk. Heck, forget being clever at all. I’d just like to have that superpower of shamelessness.

Odo

This is less about someone I wish to be like, and more about a character I suddenly understand and feel for in a striking new way.

Though he takes a humanoid form as best he can, no one thinks Odo, the changeling, really looks like them. He doesn’t understand humanoid behavior, but he does try to map it out in order to follow others’ motivations and how they lead to actions. He is impatient with the things that humanoids seem to find fulfilling and important, which to him seem pointless and wasteful. He comes off as mean when he doesn’t intend to. He craves companionship, but knows he can’t have it. And when it all comes down to it, when he’s tired of pretending to be one of the “solids,” he must – absolutely must – return to his bucket. He must resume his true liquid form, stop pretending, find total solitude, and rest.

Odo wasn’t someone I related to when Deep Space Nine first aired. But he is now.

Kirk Gleason, Abed Nadir

This brings us to today. I’ve previously written about Kirk from Gilmore Girls, how I so admire not his weirdness, per se, but his ownership of his weirdness. Do the people of Stars Hollow find Kirk a bother? Do they think he’s terribly strange? Do they find many of his actions troubling, annoying, or even destructive? Hell yes. But he doesn’t care. And he seems to fit in all the more for not caring.

Abed cares, but about the right things. He isn’t normal, and he knows it. His abnormality doesn’t bother him, nor does it bother him that people don’t get him, just as he doesn’t get them. He isn’t bothered until something about him hurts his friends or pushes them away. Then he adjusts. But not from a place of shame, but as an acknowledgement that his quirks aren’t always compatible with all the people he cares about. His adjustments are out of love, not out of shame.

“I’ve got self-esteem falling out of my butt,” says Abed. “That’s why I was willing to change for you guys. When you really know who you are and what you like about yourself, changing for other people isn’t such a big deal.”

I’m not as smart as Abed. I’m also not as overtly weird as Abed. And Abed isn’t real. But dammit, Abed, I want to live like that. Maybe one day I can be more like Abed when I grow up.

The End of the Innocence, the Wolf at the Door

I don’t want to glorify the recent past, and certainly not the crimes, both legal and moral, of the George W. Bush administration. It is difficult to overstate the damage done by that regime, the horrors of which persist in the form of various gaping, oozing wounds around the globe. Their manipulation, circumvention, and neglect of the various strands of government power were unforgivable.

I don’t want to glorify the recent past, and certainly not the crimes, both legal and moral, of the George W. Bush administration. It is difficult to overstate the damage done by that regime, the horrors of which persist in the form of various gaping, oozing wounds around the globe. Their manipulation, circumvention, and neglect of the various strands of government power were unforgivable.

And yet as we await the inauguration of Donald Trump, there is something halcyon about the years between 2001 and 2008. How could that be? With the Bush years, we saw the cynically power-mad invasion of a bystander nation, the bizarre theocratic and apocalyptic delusions of Christianists, the government sanction of torture and the wriggling out of international agreements against inhumane practices, the pillaging and demolition of the world financial system, the jaw-dropping disinterest in the destruction of New Orleans, the refusal to act on the planetary threat of climate change, and the million little ways that rights were eroded, facts were downplayed, crises were ignored, and nativist paranoias were stoked for political benefit.

And yet I’d reinstate Bush, Cheney, and the whole crew of bastards all over again if it meant we could avoid a Trump presidency. Why? Rather hyperbolic, don’t you think?

Here is where, perhaps, I am guilty of tinting my spectacles with a rosy hue. Because it seems to me that, most of the time, when norms, laws, or basic moral tenets were violated, it was done within the framework of a system that, even when abused, remained more or less intractable. In order to torture, the lawyers had to twist themselves into knots to legally justify it. When Iraq was invaded for absolutely no reason based in reality, diplomatic boxes were checked and approval was granted by great deliberative bodies. Even the failed schemes of the era were done within this framework: Bush and his allies wanted so badly to privatize Social Security, but even with their near total control of the federal government, could not muster the political force to make it happen.

They bent some of the beams and they loosened many of the rivets, but the framework held. It held so well that they were able to be defeated electorally, by congressional Democrats in 2006 (though it was to be disturbingly short-lived), and by Barack Obama in 2008 and 2012.

But this framework is imaginary, of course. And I don’t just mean that it’s a metaphor. I mean that the system itself is imaginary, a social construction, in the same way that money is. “We hold these truths to be self-evident” and all that. We collectively decide that we’re all going to abide by these rules, live within the framework. We might skirt this rule, bend that one, and others break altogether. We may break rules entirely and may lie about what we’ve done. But in all of those cases, we all acknowledge that the rules are there. The Constitution, the law, and even the unwritten norms of a democratic republic. Crimes, abuses, and neglect all happen within the framework that we all pretend is there.

Donald Trump, I fear, does not acknowledge the framework. He seems to refuse to accept its legitimacy, he makes little pretense of playing along. He may even be intellectually unable to grasp it, and in that way, he is not unlike an embodiment of the state of nature. We humans take very seriously the sovereignty of our homes, and take it for granted that our fences and walls and property lines clearly delineate our inviolable domains, but other species do not. They can’t possibly understand these concepts, and if they could, they’d certainly not take them seriously or feel beholden to them.

The social construction of our system of government, our framework, is like a home, and Trump is a wolf at the door. The wolf doesn’t know or care that you might “own” the plot of land upon which your house sits. If he can get in, he won’t feel any compunction to respect the integrity of the house, nor the lives of the people inside.

Warnings about the potentially dire consequences of a Trump presidency are not new, of course. Alarms are sounding all over the place. But even so, I read and hear a great deal of very smart, experienced people saying that Trump and his ascendant marauders will find it rather difficult to enact the kind of sweeping, draconian changes they seek. The public will have to be sold on much of it, they say. Major projects will have to be funded. The vast, sprawling federal bureaucracy will not be so easy to turn on a dime to pursue ends counter to their very reasons for being. The military will outright refuse to execute some of the more horrific orders that Trump has promised to issue.

I am not so confident. Remember back to the Bush administration, where at the very least efforts were made to justify offenses within the structure of the framework. The politicking, the legal gymnastics, the feigned diplomacy, all of it at least acknowledged there was a system to abuse. Even for those who considered the rule of law subservient to the authority of their religion were at least subject to a different framework, the even-more-imaginary dictates of their God.

My fear is that a Trump administration will not respect this imaginary framework. They will act without feeling the need to justify through legal interpretation or moral imperative. They will simply act. The Republican Party has shown itself, conclusively, to be acquiescent to Trump, and they will now control all three branches of federal power. If they choose to reject the framework, there is literally nothing they can’t do. The Democrats in Congress might have an investigation? Ignore it. Accused of breaking the law? We are the law. The public is unhappy? Lie to them. Scare them. Or don’t. What can they do? Vote you out? Elections are as meaningless now as everything else.

I fear that future generations will look back on this time of transition as the end of an innocence, when we humans thought we had built a stable, robust political and social system that existed only in our heads. How naive we were, to think that we could head off utter disaster because some rules we’d written down somewhere would serve as a bulwark against those with voracious appetites for power and wealth. That we could get the wolf to leave our doorstep by pushing a strongly-worded note through the mail slot.

Don’t you know you’re not allowed to eat the people in this house, Mister Wolf? Don’t you know it’s against the rules? Now don’t make me come out there and explain these rules to you.

Oh, alright, if I must. But you have to promise me you won’t eat me while I’m talking to you.

Please consider supporting my work through Patreon. Image by ElenaTurtle (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0).

This Situation is Awkward, and I Can't Stand Being In It

I don’t know how to react to it, and I’m worried that I may not feel enough at the time to make the right sorts of expressions on my face. How am I supposed to look? Am I supposed to tear up? Eugh. The situation is awkward, and I can’t stand being in it.This is the nearly daily experience of having Asperger’s syndrome, which I was diagnosed with this past August at the age of 38. Shortly after finding out, I read a book called Asperger’s on the Inside by Michelle Vines, a woman who around the same age discovered that the difficulties she had wrestled with her whole life were also attributable to Asperger’s. A friend of mine recommended her as a potential source for perspective after she was a guest on my organization’s podcast Point of Inquiry, and I must say, so many of Vines’ experiences and challenges mirror my own.

Not all, of course. On the whole, I’d say Vines is more interested in assertively establishing friendships and social groups than I am. In her efforts to do so, yes, there are some truly eye-opening similarities between us, but I, so often being burned by the social world, have opted out. She took a different approach, seeing her social struggles as a problem to solve, a puzzle. I wish I had more of an attitude like that.

Rather than go into a deep review of her book, which as you can imagine I mostly enjoyed (though I thought some of the attempts at humor were a little forced), I’d simply highlight some passages that were meaningful to me and reflect on them. This isn’t by any means exhaustive, but a selection of highlights that I felt I had something to say about.

On Aspie emotions:

Another example [of the challenges Aspies face] is the intense difficulties we Aspies can have with emotional regulation, which I’ve experienced firsthand. Emotional regulation is a technical term I’ve seen in online articles—sorry to feed you technobabble. In simple terms, it means that when we feel an extreme emotion, such as sadness, we can stay in that emotionally extreme state for a long time with little ability to make the feelings go away.This is definitely true for me. Often this manifests just as you’d expect; as panic, intense anxiety, or overwhelming depression (or all of the above).

Sometimes it expresses itself far more deeply within me, which is often interpreted as my holding something resembling a grudge, “dwelling,” or rudely closing off entirely. But the reality is that sometimes the feelings are so powerful or painful, the cognitive effort required to just stay afloat means I have to shut off everything external, and present a kind of low, blank disposition toward others. It’s almost as though I’m booting into “safe mode” so I can devote all my processing power to working through my overwhelming feelings. I’m sure it looks weird.

On appearing normal:

So, as you may have guessed, I, like many Aspies, was not born with an interest in fashion and clothing, or at least it wasn’t there when I was young. In my childhood and early teen years, I remember being teased occasionally on free dress days for wearing the odd daggy[19] thing my mum bought me. No one told me that you don’t tuck your T-shirt into your jeans! What’s wrong with black shoes and white trousers? Or the fluorescent-pink parachute tracksuit that my mum got me for my birthday?Oh how I wished I’d had some guidance on this kind of basic social blending knowledge, just an early seed of understanding that other people would care so goddamn much about this kind of thing, and that in order to get through the day with one obstacle fewer, it’d be wise to just check these boxes.

But no one told me. No one told me what to wear, and I didn’t care in the least, and was in fact barely aware of what I was wearing, so people made fun of my clothes. No one told me what to do with one’s hair, so it got too long and out of control, and people made fun of my hair. In southern New Jersey – which is largely populated by olive-skinned, beach-loving people of Italian descent – having a tan was considered table stakes for presentability. But I abhorred the sun, the heat, and the overall beach culture, and my genes had given me extremely pale skin that burns very easily, so I was made fun of for that all the time as well.

Also, I’m rather short, but I guess there was nothing I could do about that, though my grandmother used to tell me I failed to become tall because I refused to hang upside-down by my knees on the jungle gym. So I blamed myself for being short, too.

On communicating one’s challenges:

I started going through possible ways she and my father-in-law could respond [to my difficulties with people]. Was I going to get a talk on how I was “viewing everything wrong” or how I “need to change X and just get in there and do Y and stop overthinking it”? I guess I expect these sorts of comments, because they’re the usual reaction I get from people when I make little hints that something might be hard for me. People so often downplay my issues. “Everyone else deals with Z, so you should be fine dealing with Z too.” “Nobody likes working, but we all do it.” So that’s what I waited to hear.Asperger’s or not, this is a common refrain whenever I’ve discussed my difficulties in school, in jobs, or anywhere else. “Everyone feels that way sometimes.” The implication is, of course, that since everyone else deals with it, and yet here I am particularly aggrieved by it, there’s something wrong with me, I’m especially weak or lazy or overly sensitive for no good reason. I’m having trouble, and it’s my own fault for being effected by it.

But no, everyone doesn’t feel like this. Not like I do.

It’s interesting that I made the automatic assumption that I need to debate to justify my views and people won’t naturally respect my opinions and feelings. Being me and explaining myself has typically been so exasperating.Preach. This is a big reason why I think I overshare on my blog and on Twitter; it’s where I can, at my own speed, work through my thoughts and feelings and communicate in far more precise way. This isn’t to say that it’s always successful. But it’s better than most other means of communicating for me.

On processing information:

I am astoundingly bad with directions. I have just the worst time navigating through and orienting myself in space. This not only applies to things like how to drive from one location to another, but to things like depth perception, where parallel parking induces sweats, or playing video games (especially first-person perspective games) where I am constantly confused about my location in relation to everything else going on.

And when directions are explained to me verbally, my brain simply can’t process them. I try, I try very hard. I understand the meaning of the words being said to me, but it’s almost as though my brain immediately garbles the words so that as a whole, they are just gibberish. Even just being given a short list of basic instructions or tasks is a big mental load for me, and I have to concentrate intensely, repeat things out loud, and almost rehearse the actions in my head to be sure they actually make sense to me. Imagine how frustrating that is for my wife, who before this Asperger’s business couldn’t help but assume I just wasn’t listening.

Here’s Vines on this topic:

Sometimes, we just can’t function with so much sensory and verbal input and real-time speed. Or if the topic is not of interest, it may be hard for us to keep our focus on it in the face of other input. And I particularly wanted to bring it up in this chapter because, for such a long time, I really thought it was some sort of memory glitch that I had, and I used to kick myself for how bad I was at grasping and remembering the little details that people would tell me about themselves. I must be selfish, right? To never be able to remember the details of other people’s lives? Everyone else cares enough about other people to remember that stuff. What was wrong with me? It took me a long time to figure that one out—and a lot of guilt, I might add. So, when does this so-called memory issue affect me? Well, unfortunately, I can be pretty bad with directions.Yep. And I’m also the same with details of others’ lives. I care about other people, of course, but I also frankly suffer from an acute lack of curiosity about those details. So they never, ever stick.

On being outdoors:

How many times have people said to me, “It’s a beautiful sunny day,” or, “I hope the sun will be out tomorrow,” and I’ve privately thought, “I really hope not! I hope for a pleasant, overcast day. Please give me miserable weather! The kind that makes me relax and feel at peace.” I know that other people love frolicking out in the sun and enjoying the brightness of summer, but for me, having that direct sun on me drains my energy and has always made me, subconsciously, that little bit tenser.Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes. See my essay on the seasons from a couple of years ago, long before I knew anything about my Asperger’s.

On coping in the workplace:

I’ve had some jobs I’ve deeply, deeply hated. I know, everyone has. But while these jobs caused me unspeakable anxiety, stress, and depression, I’ve often found that I couldn’t communicate to others why I was so unhappy. When asked, “What didn’t you like about your job?” I’d find myself almost inventing reasons, or exaggerating small grievances, because I couldn’t find a way to express what was really wrong. Here’s a window into that from Vines’ own work experiences:

Within a month of starting, I began to dread going to work. On the train heading in, I would have dreams about the train crashing and sending me to hospital or the city being bombed (preferably overnight while empty of people!). I became depressed and numb Monday to Friday and spent most of Sunday crying, feeling ill because I had to go to work again the next day. I was in no way “okay.”This all rings very true. In face, the Sunday evening stress sessions became so common that my wife gave them a name: The SNAS (pronounced “snazz”): Sunday Night Anxiety Show.

When I mentioned it to people, I frequently got nonchalant replies such as, “Yeah, nobody likes working, but we all have to do it.” So after a while, I learnt to stop complaining. At the time, I had no idea that I had Asperger’s. And while I always had the sense that it must be worse for me than for other people, I couldn’t justify that feeling. …Take special note of that last thought, about dealing with unfamiliar people, and then consider that I have spent most of my post-theatre career as a PR director. Yeah, great move, right?Every place I worked, I had an overwhelming desire to get out of there. I had trouble focusing on the work and interacting with people at the same time. I would feel frustrated or angry inside and often felt like snapping at people (although I didn’t). I dreaded having to do tasks that involved dealing with unfamiliar people. It exhausted me.

The paragraph continues:

I disliked having to figure out how to do new things. Most of the time, I was given new things constantly, and I really had to force myself to start them. I had trouble remembering verbal instructions and needed to write things down. … In hindsight, perhaps I didn’t do and say the right things to project the best image of myself and promote myself to others. I needed to do things my way and plan my own time. Being micromanaged by others was too stressful. I felt sick and started to hate going to work. All I could conclude was that the common factor was me.There is a terrible fear I have of being scrutinized by coworkers or bosses. Like Vines, I want them to trust I will get the job done, but I can’t bear to have my methods or practices judged. Why? Because I always assume I’m doing it wrong, getting away with something.

Dr. Loveland, who diagnosed me, explained that these workplace experiences I describe weren’t uncommon for people with Asperger’s and that she’d heard stories like mine before. She explained to me that that “sick” feeling I talked of was the result of bottling up frustration and anxiety all day, every day. Built up over time, I suppose it manifests physiologically, causing me stomach upset, low weight, and a general feeling of being unwell.And this is why I spent my aforementioned post-theatre career in a state of sub-optimal health, to say the least. It got so bad when I worked for the 2008 Hillary Clinton presidential campaign, with the 15-hour days of intense stress, scrutiny, and pressure while packed in a giant room with people (many of whom were themselves very intense), I fell apart. It resulted in a trip to the emergency room, a scare that I might have brain cancer (I didn’t), neurological problems that manifested in my limbs and fingers, and a full-body muscle spasm or tic that I have to this day.

Had I known I had Asperger’s then, I never would have taken that job. Or I would have at least found another way to do it.

On talking to people:

I don’t usually want to, unless I have a specific reason to be curious about them, or I have some kind of investment in them, like a close friend or family member. So I don’t talk a lot around people I don’t know well, unless of course I’m the only one there, or I feel there’s an expectation, and then I blather like an imbecile.

And as I mentioned earlier, a big part of the problem is that no matter how much I try, no matter how much I know I should, I simply can’t muster any curiosity about other people. And that’s not a good start for making small talk.

Which I hate.

Here’s Vines on that:

We find [small talk] mind numbing, lacking in content, and tiresome, because we’re mainly tuning into the details and not focusing on the social or emotional purpose of the conversation, probably in the same way that typical people can find our conversation intense, overly technical, detailed, and exhausting. For me, it’s hard to come up with anything to say in a conversation that, on the whole, seems lacking in purpose.I have frustrated many a significant-other over this. “Why were you so quiet?” and “Why didn’t you ask anybody any questions?” Well, because I didn’t have any questions. I didn’t realize there was a kind of social ritual being played out.

So one tactic I might use to fill verbal space is to talk about my own take on a topic, or my own experience, and I find that this very often falls rather flat. Again, turns out it’s because I haven’t tuned into what the whole ritual is about.

As an Aspie it feels natural to respond to a conversation by relating our experiences, especially when the topic is emotional. We’re basically saying, “I know how you feel/what you are experiencing because I’ve had a feeling/experience like that myself.” To us, it’s a display that we’re actually connecting to a person’s feelings and are bonding with them. However, typical people don’t need to have had a similar experience to feel what a friend might be feeling, and they don’t need to relate that experience to show they understand. Changing the topic this way on occasion is fine, but when we do it frequently, all a typical person hears is, “me me me.”Alas.

On self acceptance:

I am not close to being in the place Vines has achieved. But I aspire.

What I really feel the need to say here is that there is nothing wrong with me. I’m just different. And any difficulties I have are the result of trying to live in a world where everyone around me is so different from me, not because I myself am faulty. I think Tony Attwood hit the nail on the head when he said, “People don’t suffer from Asperger’s Syndrome. They suffer from other people.” I’m not “wrong.” I’m everything I’m supposed to be and more. But both the social world and the business world that I live in aren’t set up for someone like me. I’m the proverbial square peg trying to fit in a round hole, and I can’t function effectively like this. I have so much potential to be useful, creative, even ingenious. The world just has to find a way to utilize me better. …The world isn’t set up for me. And I can’t make the world change for me. But maybe I can stop attacking myself over the dissonance I perceive. I play my song, you play yours. I hope I can.…

It doesn’t matter what label you carry or what cause you stand for. If you approach the world with an assured attitude and pride in who you are, other people will love and respect you for it. It’s only when you hide things about yourself that you convey that something is wrong or shameful about you that needs to be hidden.

If you like my work, please consider supporting it through Patreon.

Impact Without Agency: On the Peculiar Character of 2016

The skeptic in me – the one whose rationality was inspired by Carl Sagan, the one that must force himself to be politic when talk of God, psychic abililities, or superstitions come up, the one whose actual job is to be the voice of an entire skeptics’ organization – knows, for certain, that there is no curse attached to the calendar year 2016. There is nothing special about this particular trip around the Sun for our planet, nor is there any negative “energy” or force particular to this year that makes it any more or less eventful or tragic. 2016 has no magic power for killing celebrities.

I know that tens of thousands of people die every day. (And as my podcast co-host Brian Hogg is wont to remind us, the real tragedy there is that we never know that any of them ever existed.) And celebrities also die. That they seem to be dropping at a higher rate this year is attributable to any number of banal things.

Terrible national and global events happen in every year. Is it’s not political upheaval in one country its a natural disaster in another. Usually it’s both. 2016 may seem more tumultuous simply because this time it’s happening to us in the United States, you know, the Only Country That Really Matters™.

And of course, we all lead lives of varying degrees of drama, triumph, and misery. We all go through major life changes, endure challenges, learn new things about ourselves, and all the while the people we love do too. In some years more, in some years less.

And yet.

I had been thinking about writing about this subject – the “cursed” 2016, the Year of the Dumpster Fire – for some time, but I kept holding off, guessing that something might yet still happen, some big kick in the face, punch in the gut, or other metaphorical impact with a body part. I or a family member might find our lives upended, another beloved public figure might unexpectedly drop dead, another world event might Change Everything once again.

Of course, “2016” didn’t kill Carrie Fisher. Or George Michael. Or Prince or Bowie or Rickman. 2016 didn’t elect Donald Trump, or push the North Carolina state government to reject democracy. 2016 didn’t set loose the horrors of Syria or the attacks in Berlin, Nice, Orlando, or anywhere else. I know this.

But I also think it’s okay to recognize that these things did all happen during this year. Arbitrary and invented as it may be, the calendar is how we human beings conceptualize the passage of time and how we understand our history. So whether or not there is any preexisting or preordained “meaning” to the gathering of events between one January and another, we can’t help but experience it as a whole, of a piece. 2016, whether it’s logical or not, has a particular character to it.

For me, the year has been truly extraordinary, with highs, lows, and major discoveries that I’m just beginning to comprehend. Just off the top of my head: I found out that I’m autistic and my brother was diagnosed with fucking eye cancer (and then dozens of people pitched in to help him pay for medical expenses).

(I also went through far fewer phones than last year, only two tablets, and one pair of headphones. Take that, 2015!)

And while 2016 isn’t cursed, events do cascade to initiate other events. For example, it now seems clear that the madness of the GOP presidential primaries, both horrifying and hilarious at the time, could not be contained within the strict confines of a singular political party’s zealots. The fire raged into the general electorate, and Donald Trump wound up being elected by technicality. It didn’t happen “because it’s 2016,” but it did happen in 2016 because events that also happened to take place in temporal proximity set its eventuality in motion.

There are still four days left in 2016 as I write this. I can’t help but feel genuine anxiety about what yet may come during that time. And if some new earth shattering event occurs on January 1, 2017, it simply won’t feel like it’s part of the same whole. It will be its own era, a new volume to the chronicles. But it will also be irrevocably knocked askew by the events of 2016.

Not because a vaguely-sentient 2016 made them happen. But because they did happen in 2016. And it’s okay to take that in, to feel it in your chest. You don’t have to ascribe agency to the year to acknowledge its impact. It’s okay to think of that particular arrangement of four numerals, then pause for a moment, and feel a sense of dreadful awe.

If you like my work, please consider supporting it through Patreon.

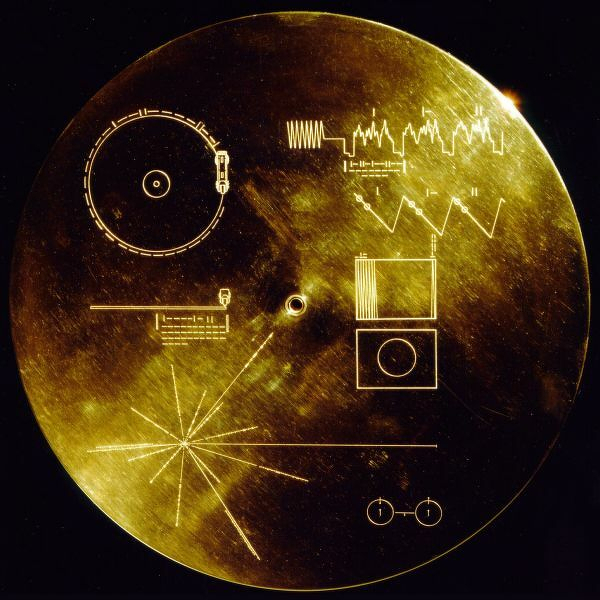

In a Dark, Confusing World: Carl Sagan, 20 Years Gone

Ten years ago today I wrote a piece about the impact Carl Sagan had on my life, commemorating what was then the tenth anniversary of his death.

Ten years ago today I wrote a piece about the impact Carl Sagan had on my life, commemorating what was then the tenth anniversary of his death.

Today, obviously, Carl Sagan is 20 years gone, so I’ve dusted off the original piece to see if it still holds up. It does. Every word of it remains true. (Except I might today not talk about being “excited” to live in the world, but, you know, I grow more curmudgeonly and Asperger-y as I age.)

So, to mark two decades of being Carl-less, here’s “Why Paul Was Sad That Day,” written December 20, 2006. I’ll have additional thoughts at the end of the original piece.

*

I don't remember where I was when I first heard that Carl Sagan had passed away, but I do remember where I was later that night. I was in college, hanging out at my friend's apartment. A few close friends were there, and I brought up the news item of Dr. Sagan's death.“Carl Sagan died today,” I said, sadly.

“Who’s Carl Sagan?” was the reply.

I was totally surprised, because I assumed everyone knew who he was. I didn’t expect that most people had read a bunch of his books, or had seen Cosmos (recently, anyway), but surely he was famous enough to warrant recognition by my friends at least. I mean, Johnny Carson had imitated him! “Billions and billions!” Come on people!

I tried to convey to them why it was so bad that we had lost this important man, and while my friends played along and humored me, I really couldn’t get my message across. I would have to grieve a little more privately. It was too lonely to be openly morose about the death of a man who, to everyone I was with, was no more than some guy that nerds worship for space or something. Maybe now, ten years later, I can have another go at it.

When Cosmos first aired, I was too young to understand any of it, at age three or four. It wasn’t long after, though, maybe only a couple of years, that my dad played me the series, recorded on videotape (on Beta, no less). He knew I was interested in space, but only inasmuch as it was a location where Star Wars took place and the Transformers came from. Would I sit still for a lengthy PBS series on the real thing?

Not only did I love the series as a child, but I would continue to love it as I grew up. Having the entire series on videotape was a tremendous blessing, as I would watch it in its entirety every couple of years for most of my childhood, well into college. In our house, Carl Sagan was a huge celebrity, frequently cited (and imitated). We would be delighted to see him appear on other shows, or be referenced or made fun of by comics. But what was it that was so great about him?

Carl Sagan was a gifted storyteller. Even to a fifth grader, the story of evolution, the birth of the solar system, the building of DNA, or the death of a star were all as fascinating as any fictitious story about monsters or aliens. While these things were no doubt of passing interest to me as long as I can remember, Carl Sagan made them thrilling.

As I got older, and read his books, I realized that he was about more than appreciating how cool outer space was. My appreciation for his work deepened tenfold when I heard his call to rationality. His dismissal of superstition and shortsightedness was influential to me even in the early part of my life, but it was upon reading The Demon-Haunted World that I had a framework to discuss it. I had a means to verbalize and visualize what had always been to me simply an abstraction, wanting to be logical and thoughtful. Carl Sagan shifted, in my mind, from a celebrity to a role model.

With Dr. Sagan, you didn’t need to layer on any supernatural hocus-pocus for the world to inspire and overwhelm. Biology, chemistry, and physics were plenty astounding on their own. And it wasn’t for science’s sake, or even for wonder’s sake. It was for our sake. Sagan knew that to understand our Universe, and to marvel at life on our planet, was to cherish it, and to work to preserve it. And by preserving it, we preserve ourselves. If there’s anything I think Carl Sagan wanted, it was for humans to survive into the millennia, so we can get a fair shot at growing, evolving, and unlocking more of the Universe’s secrets. He essentially wanted us to stay alive, and not to stay put.

I have been a professional actor and musician for many years, and I am now moving into the world of professional politics. I am not, and probably never will be, a scientist. But if Carl Sagan’s goal was to open the wonders of science and the value of reason to non-scientists, I am his poster boy. I think Sagan’s purpose was not necessarily to make scientists, but to sow an appreciation and enthusiasm for the Universe as it actually is. Even though my career and career-to-be are not strictly about the workings of the world at the quantum level, the appreciation for those things that Sagan has fostered in me has made me excited to live in this world and inspired me to understand it and work toward its welfare.

I have been a professional actor and musician for many years, and I am now moving into the world of professional politics. I am not, and probably never will be, a scientist. But if Carl Sagan’s goal was to open the wonders of science and the value of reason to non-scientists, I am his poster boy. I think Sagan’s purpose was not necessarily to make scientists, but to sow an appreciation and enthusiasm for the Universe as it actually is. Even though my career and career-to-be are not strictly about the workings of the world at the quantum level, the appreciation for those things that Sagan has fostered in me has made me excited to live in this world and inspired me to understand it and work toward its welfare.

Today, I read the works of folks like Richard Dawkins, Tim Ferris, and Brian Greene, and I devour their words and delight in the struggle to wrap my brain around concepts like branes, supersymmetry, and Bussard collectors. The problem is that I never would have taken the plunge into the world these scientists inhabit if Carl Sagan had not opened the door for me in the first place. I fear that without someone like him today, someone who can ignite the imagination as he could, far too few people will be drawn to science and reason. In a dark, confusing world that seems to be shying further and further away from those very things, I mourn the loss of Carl Sagan anew, on this day, the tenth anniversary of his death. I wish so very much he was still with us, because we need him today more than ever.

And that, my college friends of 1996, is why I was so sad that day.

*

Back to 2016. That last sentiment, that we need Sagan now more than ever, has only become more true. Only yesterday, our Electoral College formalized the election of a man to the presidency who embodies the brazen rejection of everything good Sagan represented. Misinformation is the rule now, not the exception. Conspiracy theory and emotion-fueled irrationality is the coin of the realm. Planetary-level existential threats, the kinds that Sagan would have given all of his energies to working against, are now accelerated.

If there exists an individual or individuals who have the inspirational power that Sagan possessed, I’m not aware of him or her. Many come close. But I’m afraid that they don’t come close enough. I do hope I am wrong.

If you like my work, please consider supporting it through Patreon.

On Trump and Dying

Postulated model for the series of emotions experienced by electorally defeated voters to the imminent inauguration of Donald Trump.

Stage 1

Something must have gone wrong with the voting process. Recounts of close states will reveal that the vote had been tampered with by the Republicans. Or the Russians. Or both. There’s no way America is home to so many racists and fools. It’s just not conceivable. Something is up.

Stage 2

GOD DAMN THOSE RACIST MOTHERFUCKERS. This is all those idiots’ fault! And James Comey and the FBI, those BASTARDS had it in for Hillary from the beginning! But of course that wouldn’t have mattered if it weren’t for those lazy, entitled millennials who COULDN’T BE BOTHERED TO TURN OUT even though the stakes were so high. That’s goddamn BERNIE’S fault! And why the hell did the Clinton campaign ignore Wisconsin and Michigan? ARE THEY COMPLETE IDIOTS?

And WHY is NO ONE just SCREAMING IN THE STREETS about RUSSIA???

Fuck everybody!

Stage 3

Listen, electors. C’mere. Listen. Guys. And ladies. I know you’re not going to let this happen. Come on. Seriously. Let’s talk. Russia messed with us. Trump’s going to ruin everything. You know it, I know it, and you know what? We can do something about that, right now. You all can be goddamned heroes. You Trump electors have to vote for Clinton. After all, she won the popular vote by a huge margin! Almost 3 million votes! Democracy! You should switch sides and vote for Clinton.

Okay, fine, then we should all pick a consensus Republican that we can all feel good about. Let’s talk President Romney. President Kasich. Clinton electors, you can get down with that, right? Better than the alternative, right? Right? You know I’m right.

Fine fine fine. Okay. Listen. We just need enough of you Trump electors to vote for anyone else. Literally anyone else. Okay? Then we’ll throw the election to the House, and then we’ll talk to them. Maybe we can get President Pence. One of you electors, vote for Pence, okay?

Guys?

Stage 4

It’s over. America. It’s over. And it’s our fault. All of us. I could have done more. I could have donated more, I could have knocked on doors. But I didn’t. Neither did you. We’re terrible. We deserve this. America. We stare at our TVs and our phones, we fall for fake news and obvious bullshit, we eat it up. We’re an empire in rapid decline, and we brought it all on ourselves. With our consumerism and our coastal hubris. There’s nothing to be done. Everything is going to fall apart. Why bother even giving a shit? I don’t care anymore.

Stage 5

This is going to be exactly as bad as we think it is. And we have to get through it. Somehow.

Get ready.

If you like my work, please consider supporting it through Patreon.

The Electors' Moral Duty

I am entirely opposed to the Electoral College as a means of choosing the President of the United States. I proudly worked for an organization that had repeal of the Electoral College, replacing it with a national popular vote, as one of its three or four prime reasons for existing.

But that’s what we’ve got right now. While I’m horrified that it has allowed Donald Trump to become the president-elect, I don’t believe that his election is “unfair” just because Hillary Clinton overwhelmingly won the popular vote. Both campaigns ran to win the Electoral College vote, not the popular vote, and Trump succeeded. That’s the game both of them were playing. If it had been a popular vote contest, they absolutely would have run entirely different campaigns, and it’s impossible to say for sure what that outcome would have been (though we can guess). Hillary knows it. Al Gore knew it. Them’s the breaks.

As the electors themselves are about to vote, there is a lot of noise about whether some of them will “defect,” as it were, and that some of those who are pledged to Donald Trump will vote for someone else, or not at all. There are talks of secret discussions, compromise candidates, legal challenges, intelligence briefings, and postponements.

I don’t think anything is actually going to happen. Sure, one or two electors may ultimately vote in contradiction to their pledge, but I do not believe we’re going to see anything that changes the result of the election.

But I do support the efforts to do so, and I hope I am wrong that nothing will change.

It’s not a simple matter. Changing the result of the election will have enormous consequences, the likes of which we can’t yet predict. Put aside the legal and constitutional questions, put aside the totally unprecedented confusion over transitions and appointments that will transpire.

Merely imagine for a moment a scenario in which, by one mechanism or another, Trump is denied the presidency in favor of another candidate, be it Clinton or a GOP compromise candidate. I cannot believe that such a reversal would not spark chaos among the populace. I’m talking actual riots and violence from angry Trump supporters, supporters who are not exactly peaceful and friendly in victory, let alone defeat. People will be hurt, some may be killed, the economy will take a rollercoaster ride, and whatever regime does wind up taking power will be debilitated in myriad ways: choked by a thick cloud of illegitimacy, pilloried by hails of lunatic conspiracy theories and vicious opposition from the far right, and who knows what else. It will be awful.

But it will pass, eventually, and even in the worst imaginings, it will be better than a Donald Trump presidency.

I know I am on record months ago as believing that Trump was preferable to, say, a Cruz or Rubio presidency, but I of course have been thoroughly disabused of this, and I would gladly welcome a President Ted Cruz over what we’re about to endure. More likely, if there was some kind of alteration of the election, we’d be looking at a President Mitt Romney, Mike Pence, or John Kasich. Fine. Great. Welcome to the Oval Office. Nice to have you.

Why is this better than just coping with the status quo and dealing with whatever comes of a Trump administration? Here are some things a Trump presidency will, with near certainty, mean. They require almost no speculation, just common sense:

- Climate change will accelerate beyond the point that humans could do anything to mitigate

- The Supreme Court will lurch far to the right, perhaps for generations

- Putin’s Russia will become far more powerful and audacious

- Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and other badly needed social programs will be gutted or destroyed entirely

- The Affordable Care Act will be mutilated or repealed, and millions of Americans will lose their insurance

- American police will become even more militarized, and incarcerations will go way up

- Public education will lose funding in favor of private and religious schools

- The EPA and the FDA will be neutered, if not abolished altogether, or else turned into marketing tools for the industries they are supposed to regulate, putting millions of lives in danger

- The poorest Americans will become poorer

- Minority groups will have their voting rights strangled to the point of de facto disenfranchisement

- The press will be stifled and under constant threat of retaliation from the government

- Nazis, white supremacists, men’s rights advocates, and other blights on humanity will complete their exit from the shadows and become normal parts of American public life and politics

The members of the Electoral College, I feel, have a moral duty to stop this.

I think it’s worth the short-term risk of chaos and the loss of confidence in the Electoral College system. It’s worth these citizens violating their vows to vote as directed by their states. The electors are human beings, Americans who have to live in this country, and on this planet, too. But they are also Americans who by dint of circumstance have the power to save us, and one chance to do it.

They won’t. I’m nearly sure of it. But I really hope they do.

If you like my work, please consider supporting it through Patreon.

P.S.; Here’s an interview Lawrence Lessig just did with the Washington Post, discussing his initiative to confidentially assist any electors who are considering taking action like this.

Hereafter, in a Better World Than This...

This is a song I wrote in 2006 for a production of As You Like It that suddenly felt rather appropriate for this moment. So I thought I’d sing it for you all.

The old world we knew is falling away; It's proven difficult to accept. And I had been feeling like I'd lost my way Before I'd taken my first step.[youtube [www.youtube.com/watch](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8JGdnQMuk-M?rel=0])

What We Told Our Kids Today

Our two children, our 6-year-old son and 4-year-old daughter, were very enthusiastic about this election. From the beginning, they’ve shown an enormous amount of genuine curiosity about it, and became quite emotionally invested. Of course, that’s because their parents were too.

We certainly knew that a Hillary Clinton presidency was not a foregone conclusion, and that it would not take some sort of upheaval or miracle for Donald Trump to defy expectations, but like most of the human species, it appeared so unlikely as not to warrant too much worry. So that’s what we shared with our kids. Optimism about the outcome, always grounded in the very real possibility that we were wrong.

They were excited that a woman might be president. We read them biographical children’s books to them about Hillary Clinton, and they truly admire her, as my wife and I do. They were comically hostile to Trump, with my son devising elaborate offensive machines that would batter Trump with multiple frying pans should he ever come to the door seeking our votes. My daughter was more concise, promising to “smack him in da FACE.” I discouraged the more overtly violent fantasies, but it was all in fun. (When I informed my son that Clinton had “kicked Trump’s butt” in the debates, he paused and clarified, “Metaphorically.” Yes, son, metaphorically.)

Among our many agonies on election night, my wife Jessica and I were sick over how to tell the kids what had happened in the morning. Jess was very worried, afraid that our son, who is at a very emotional phase, would panic. If the grownups were in tears, our sensitive kids would be too.

This morning, I snuggled up to my son in his bed, cuddled him close. Thumb in mouth, he rested his half-sleeping head on my chest. I rubbed the close-cut hair on his head, and wished I could lay there with him for hours.

Jessica came into the room, and as our son became more awake, she calmly broke the news in a gentle, measured, loving voice. “Donald Trump won the election.”

Over the course of the morning, here’s the gist of what we told our daughter and son.

We’re all okay.

There is no doubt that the election of Donald Trump is bad news. We absolutely don’t think he should be president. Maybe more importantly, we know that Hillary Clinton would have been an amazing president. We’re pretty sad, and a lot of people are going to be feeling very bad about this for a while.

Donald Trump is a man we disagree with on almost everything, but we in this family are going to be just fine. We won’t at all like a lot of what he does or tries to do, but he’s not going to “come and get us.”

Here’s what we can do now. For all the things we don’t like about the man who will soon be president, we can choose to be better. We can be kinder to the people in our lives, and help the people who need it. We can love each other and always be looking for ways to make our home and our community a better, happier place. It’s actually the most powerful thing we can do.

Remember that not everyone agrees with us. [Note: My son’s first grade class voted unanimously for Clinton in their mock election, but Trump eked out a victory in my daughter’s pre-K class.] When you go to school and when you’re around other people, remember that some of them are happy about this election, and others are very upset. Don’t be mean to the people who voted for Trump, and be gentle with those who didn’t. The idea is to put more love and kindness into the world, not less.

There are many people out there in the country and in the rest of the world who will have a much harder time with Trump as president than we will. We are very lucky in that we will be okay, and our lives will be just about the same. Others will have new troubles, and we need to help them however we can.

That’s more or less what we told them.

For our daughter, we were very clear and optimistic and passionate on one particular point: You can be anything you want to be. You can be president. You can accomplish whatever you set out to do. I think we told her this for our own sake as much as hers. I had brought her into the voting booth with me on Election Day, so she could be there when I voted for who we thought would be the first women President of the United States. Though she didn’t feel this way, I felt that more than anyone else we had let my daughter down.

After we first told our son what happened, as I held him to me in his bed and could not see the first reaction on his face, I worried how the news was hitting him. He lifted his head up, got to a sitting position, and my 6-year-old boy spoke.

“Can I write a letter to Hillary Clinton?”

He wants to write to her to tell her how sorry he is that she lost, that he knows she worked so very hard, and that he doesn’t want her to be upset.

That was his first reaction to the news.

If Jessica and I have succeeded in anything in our lives, it is in that we have brought into the world two human beings with good, loving hearts. They are kind, they are compassionate, they are empathetic. I am so deeply proud of them.

We proceeded through our usual Wednesday morning routine, and though heavy with the weight of what has happened and what is to come, we still had silliness and hugs and jokes as well as the mundane frustrations of getting out the door in the morning. My kids made me laugh, they got on my nerves, my son forgot his backpack so that we had to go back home to get it, and my daughter agreed to become president one day, before going to pet the preschool class’s bunny.

This is not a trivial thing. My family and I, along with tens of millions of human beings, have been let down by a huge portion of our fellow citizens. We were betrayed by legions of cynical opportunists, self-righteous purists, the blamelessly uninformed, the willfully ignorant, and the overtly malicious. Not only has a fascistic clown been elected president, but we’ve been denied the leadership of perhaps the most qualified, competent, and skilled president our country could have ever had. There is darkness coming.

But there is also light. My sensitive, curious, imaginative boy and my brilliant, brave, creative girl. They are luminous.

If you like my work, please consider supporting it through Patreon.

The Long Climb Up to Zero

I’m on my way back from CSICon, the skeptics’ conference put on by my organization, which took place in Las Vegas this year. One of the presentations was by Anthony Pratkanis, who introduced us to the phenomenon of “altercasting,” wherein a person can elicit desired behavior from others by adopting, and implicitly assigning, particular social roles. So for example, if he effectively assumes the social role of a teacher, we become students, and will find ourselves carrying out the behaviors that are expected of that role (dutifully taking notes if he suggests it, for example). And the power of this altercasting is such that once we have put ourselves into these social roles, we live up to them. We almost can’t help it. It’s a tool of con artists, as well as a skill that can be used for good.

On my way in to Vegas, I got a message from my wife asking if I knew what day it was. Uh oh, was my first thought. But then she reminded me: the sixth anniversary of the night I was ambushed late at night by two thugs on the street in DC, beaten to a bloody pulp, and sent into a years-long spiral of PTSD and myriad other associated problems. The anniversary date used to have a lot of power over me, almost as though the recurrence of the date would somehow “make it happen again,” which is of course nonsense. In the past couple of years, though, I’ve more or less let the day pass without realizing it, which is a small victory.

The years of therapy that followed this event, which I’m still working through, subsequently unearthed the vast array of phobias, self-loathing, weird hangups, anxieties, traumas, and other psychological baggage I’d been lugging around more or less since childhood. The PTSD diagnosis, it turned out, spanned far more than just one attack. I had been trained to experience existential terror, fight-or-flight amygdala activation, through years of bullying and abuse in my youth. In other words, I was early on placed in the social role of a subhuman target for derision. And with constant reenforcement, I lived up to it. I memorized it.